When operations or steps get omitted, a common countermeasure is to establish a checklist.

A typical checklist has a list of items or questions – sometimes even written in the past tense.

“Was the _______?”

There are a couple of common problems with this approach.

First, the time to actually, physically make the checks is not included in the planned cycle time. This implies we are expecting the team member to review the checklist and remember what she did.

The second issue is that the team member often does remember doing it even if it wasn’t done.

This is human nature, it isn’t a fault or flaw in the individual. It is impossible to maintain continuous conscious vigilance for any length of time. There are techniques that help, however they require some discipline from leaders.

Overall, a checklist that asks “Did you___?” in the past tense is mostly ineffective in practice.

We make things worse when the checklist is used as a punitive tool and we “write up” the team member for signing off on something that, actually, didn’t get done. Most of the time it does get done, but everyone in this system occasionally misses something. Sometimes those errors get caught. This kind of “accountability” is arbitrary at best.

Where checklists work is in “what to do next” mode – referring to the check list, doing one item, checking off that it was done, then referring to the next item on the list. This is how it works in an airplane cockpit.*

CAPTAIN: okay, taxi check.

FIRST OFFICER: departure briefing, FMS.

CAPTAIN: reviewed runway four.

FIRST OFFICER: flaps verify. two planned, two indicated.

CAPTAIN: two planned, two indicated.

FIRST OFFICER: um. takeoff data verify… one forty, one forty five, one forty nine, TOGA.

CAPTAIN: one forty, one forty five, one forty nine, TOGA.

FIRST OFFICER: the uh weight verify, one fifty two point two.

CAPTAIN: one fifty two point two.

FIRST OFFICER: flight controls verify checked.

CAPTAIN: check.

FIRST OFFICER: stab and trim verify, thirty one point one percent…and zero.

CAPTAIN: thirty one point one percent, zero.

FIRST OFFICER: the uh…. engine anti-ice.

CAPTAIN: is off.

FIRST OFFICER: ECAM verify takeoff, no blue, status checked.

CAPTAIN: takeoff, no blue, status checked.

FIRST OFFICER ON PA: ladies and gentlemen at this time we’re number one for takeoff, flight attendants please be seated.

FIRST OFFICER: takeoff min fuel quantity verify. nineteen thousand pounds required we got twenty one point eight on board.

CAPTAIN: nineteen thousand pounds required, twenty one eight on board.

FIRST OFFICER: flight attendants notified, engine mode is normal, the taxi checklist is complete sir.

(This is also how it works when assembling a nuclear warhead, but I can’t tell you that.)

This is also very effective for troubleshooting. For example, I was working with a team in a food processing plant. The obstacle being addressed was the long (and variable) time required to change over a high-speed labeling machine and get it “dialed in” and running at full speed without stops and jams.

Some operators were much better at this than others. We worked to capture an effective process of returning the machine’s settings to a known starting point, then systematically adjusting it for the specific bottle, label, etc. It worked when they were able to slow down enough to use it. That was an instance of “Slow is smooth; smooth is fast.”

The act of reading out load, performing the action, and verbally confirming is very effective when it is actually done that way. Even so, people who are very familiar with the procedure will often take shortcuts. They don’t “need” the checklist… until they do.

Still, you have a sequence of operations, and it is critical that they are all performed, in a specific order, in a specific way.

What works?

I’d say look around.

If you are reading this, you likely have been at least dabbling, and hopefully trying to apply “lean” stuff for a while.

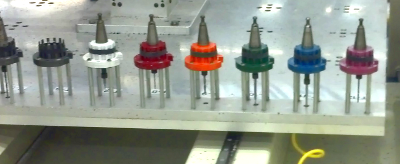

What is a basic shadow board? It is a “checklist” of the tools to confirm they are all there – and a lot faster because missing items can be spotted at a glance. At a more advanced level, companies move away from shadow boards and to having the visual controls outlining what should be where to perform the work.

If you kit parts, you can set them out in a sequence – a “checklist” that cues the team member what order they should be installed.

I could continue to cite examples, but here’s the point.

When things are being left out, there is a high temptation to say “Let’s make a checklist” and sometimes make it worse by saying “…and we’ll have the worker sign it off for accountability.” That is more often than not simply a “feel good” solution. You feel like you have done something, and I’ve even heard “Well, it’s better than nothing.” I’m not sure it IS better than nothing – at least not in very specific conditions.

Instead, you need to study the actual work. Don’t try to ask questions, just stand and watch for a while. (Explain what you are doing to the team member first, otherwise this is creepy. “Hi – I’m just trying to understand some of the things that might get in your way. Do you mind if I just watch for a while without bothering you?”)

What cues the team member which step to perform next? Does he have to know it from memory? Or is there something built into the way the workplace is organized?

Does he end up going back and doing things he forgot?

Does he set out parts and tools in order on his own so he doesn’t forget?

Does he get interrupted, by anyone or anything, that takes him out of his mental zone?

(I go through airport TSA security checkpoints at least twice a week. I have a routine. When the TSA agent tries to “help” by talking to me, my routine gets broken, and that is when I forget stuff.)

If you are coaching someone, it helps if you go there with them, help the see the details by spotting these things and “asking” about them; then taking them to another area and challenging them to see as many of these issues as they can. See who can spot more of them.

What you are seeing are obstacles that impact the team member’s ability to do quality work.

Checklists don’t help remove those obstacles.

___________________

*The checklist transcript here is a cleaned up version of the Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript from Cactus 1549, the US Airways A320 that successfully landed in the Hudson River after multiple bird strikes knocked out both engines. I used it here because it is authentic, and the accident was one where everything went right and no one was seriously injured.

This is so helpful. Just a few weeks ago I told one of my coworkers to “get a checklist in place” with our supplier who was having issues with shipment accuracy. Looks like I need to rethink this and actually work to fix their process!

Hi Sam –

In a pick-pack and ship process, if there is a verification of the pick, it is best performed by someone other than the person who picked the order. That way they are operating with no assumptions about what is there.

However, there are other common sources of pick errors, including picking OR packing multiple orders at once for example – which gives items an opportunity to “migrate” between orders and end up in the wrong box.