Many years ago I wrote an article for SME called The Essence of Jidoka. In that article I described a four step process designed to improve productivity and drive continuous improvement. Since then these four steps have been picked up and incorporated into the training materials of many consultants, used to write the Wikipedia article on jidoka (which I most assuredly did not author), and even found their way into some academic papers. Sometimes with attribution back to my article, may times without.

In that article, “jidoka” was described as a four step process:

- Detect a problem.

- Stop.

- Fix or correct the problem.

- Find the root cause and implement a permanent countermeasure.

But I would like to take a hard look at the first step: Detect the problem. This is where, I believe, most organizations actually fall down. And in doing so, they also fall down on respect for people.

The key question is: “What do you consider a problem?”

Most organizations do not see a problem until the symptoms are bad enough that they are compelled to do something about it. This means people have been struggling with issues for some time already. The machine isn’t reliably producing good parts. Or someone is having to rework material. Or the supplies cabinet is always short, and the nurses have to launch a safari to find what they need.

Contrast this with a company like Toyota. Every Toyota-trained leader I have ever dealt with is very consistent. A problem is any deviation from the standard. More importantly, a deviation from the standard (1) forces people to improvise and (2) is an opportunity to learn.

This definition, of course, leads to a question: “What is a standard?”

Probably the best explanation to date is in the research done by Steven Spear at Harvard. His work was summarized in the landmark article Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System.

Spear’s research concluded there were four tacit rules for how activities, information connections, flow paths, and improvements were designed and executed in Toyota operations. Each of those rules describes:

Any deviation from the standard triggers some kind of alert that gets someone’s attention. And whose attention is explicitly defined – That is a standard as well.

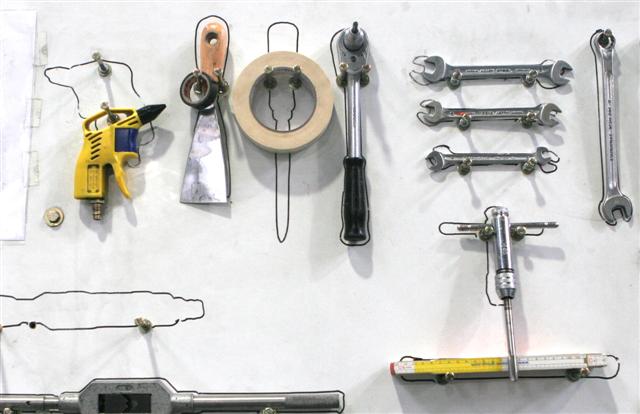

As I look at a work area, I often see a lot of 5S type of activity. Things and their intended locations are marked and labeled. These are standards. They establish what should be where. But the question to ask is “What happens if something is out of place?”

That is a deviation from the standard. It is a problem.

Stop

Fix or Correct (put it back – restore the standard condition)

Investigate the root cause

“What’s going on with the air wrench today?”

“Actually it is an extra one.”

“Really? Where did it come from?”

“I borrowed it from the Team Member in work zone 3.”

“Ah, OK. Why did you need his?”

“The regular one isn’t working.”

“Hey – thanks for letting me know. I’ll get it to maintenance.”

“Thanks”

“Did you tell anyone about the problem before now?”

“No, I just borrowed the wrench. I just needed to get this job done, then forgot. It’s no big deal, it’s easier to just borrow Scott’s wrench.”

And in that exchange, what have you discovered about your daily management system by simply being curious about a trivial deviation from a 5S standard?

Is this the Team Member’s fault?

Probably not. What is your standard? What is he supposed to do if the wrench stops working? Is there an escalation process and a response for this kind of small stoppage? Or are your Team Members just expected to find a way to work through the issue? Which of those responses is more respectful of the Team Member who spends her time trying to create value for you?

Often times there is no standard.

But without a standard you have no way to tell if there is a problem (other than a feeling that something isn’t right). And if you are sure there is a problem, without a standard you can’t really define what “fixed” is.

So start with defining the standard. First, go back to Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System. You can get an idea of the kinds of things you should standardize.

As you think of standards, consider a standard for your standard:

- Express it from the viewpoint of the process customer.

- Define it in a way that can be verified as “met” or “not met.” No gray zones. You can quantify the magnitude of a problem, but not whether you have one.

- There is a visual or other control tells the appropriate person, right away, if there is a deviation from your standard?

- Is there a standard that triggers a response to clear the problem?

5S is nothing more than the first step of setting standards. Many people say to start there, but don’t say why. The point is to practice setting standards and holding them. Taiichi Ohno is quoted as saying:

“If there is no standard, there can be no kaizen.”

Any deviation from the standard is a problem.

Your choice, as a leader, is how to handle that problem.

This post makes some really great points. I had not previously considered that any deviation from the standard is a problem. This is helpful advice to people seeking ways to improve processes, through the first step of diagnosing a problem. Problems can be diagnosed by comparing to the standard, however standards should also be established in order to diagnose processes that can be improved.

Awesome read, it shows many great points. It’s true, a problem isn’t known until it’s already too late and needs to be addressed right away. But anything that isn’t standard is an issue and should be addressed and fixed. So creating a standard at the beginning is the best way to reframe from having issues.

I thought this was a really interesting way of thinking and trying to solve a problem. I haven’t thought much about how companies do not see a problem until it is too late, which can make it more challenging to solve. I also never thought to define what a problem is, so the idea of a standard was really eye-opening. Having a set standard will make it much easier for companies to diagnose and solve a problem before it gets out of hand.

Sofia –

One of the challenges is that most companies frame a “problem” as an issue with the outcome. What we need to do is back things up and look for an issue with the process. That is respectful of the people we are asking to achieve an outcome by carrying out a specified process. If we look at outcomes alone, especially metrics that people perceive as evaluating them, there is an extremely high risk that people will find ways to manipulate the process or measurement system to deliver the number. That might not be the process we actually want.

I enjoy hearing about others experiences reading articles then explaining it though the lean and six sigma thinking. My favorite observation was that a problem is a deviation from the standard. You can ask a worker what problems they are having but if they don’t understand the issue of going off standard they might give you problems or issues that aren’t directly related to the end goal of the process. Which leads into the most important part which is asking questions in the gemba. This forces workers to critically think to come up with a viable solution. Lastly the standard need to go back into place to see future problems. This proves the point that “If there is no standard, there can be no kaizen.”

The question you can ask to help frame the thinking of “desired vs. actual” is, “Well… should should be happening?”

That can be more effective than introducing jargon or trying to define “standard” etc.

Another question is “What stops you from doing this perfectly?” rather than “Why…” questions which can invoke defensivness.

Great post!! I can fully relate when you talked about how companies don’t see the problem until it it too late. I work for a company that has so many problems and when I come in I’m the one who has to come in and do the damage control and fix all of the problems. But at the time that problem was very small and easy to fix but because they didn’t fix it in that time it snowballed and created more problems. So as one of the managers I am going to have them read this article and understand the four step process. Thank you!