With the publication of Learning to See in 1999, Mike Rother and John Shook introduced a new genre of book to us – a mix of theory, example, and practical application. The story invites the readers to follow along and actually do for themselves.

With the publication of Learning to See in 1999, Mike Rother and John Shook introduced a new genre of book to us – a mix of theory, example, and practical application. The story invites the readers to follow along and actually do for themselves.

This is one of those books that gives a bit more every time I read it. The more thorough my baseline understanding of TPS, the more I get from some of the nuances of Rother and Shook’s intent.

At the same time, I am beginning to formulate an idea that perhaps this book is often used out of its intended context – maybe a context that was assumed, but left unsaid.

I’d like to share some of the things I have learned over the years, especially as I have worked to integrate the concepts in Learning to See into other facets of the TPS – especially research by Steven Spear, Jeff Liker, and of course, Mike Rother’s follow-on work Toyota Kata with my own experience.

Value Streams

Learning to See introduced the term “value stream” to our everyday vernacular.

Although the term is mentioned in Lean Thinking by Womack and Jones, the concept of “map your value streams” was not rigorously explained until LTS was published.

To be clear, we had been mapping out process flows for a long time before Learning to See. But the book provided our community with a standard symbolic language and framework that enabled all of us to communicate and share our maps with others.

That, alone, made the book a breakthrough work because it enabled a shorthand for peer review and support within the community.

It also provided a simple and robust pattern to follow that breaks down and analyzes a large scale process. This enabled a much larger population to grasp these concepts and put them to practical use.

Learning to See and “Getting Lean”

In Chapter 11 of Lean Thinking, Womack and Jones set out a sequence of steps they postulate will transform a traditional business to a “lean one.”

The steps are summarized and paraphrased in the Forward (also by Womack and Jones) of Learning to See:

- Find a change agent (how about you?).

- Find a sensei (a teacher whose learning curve you can borrow)

- Seize (or create) a crisis to motivate action across your firm.

- Map the entire value stream for all of your product families.

- Pick something important and get started removing waste quickly, to surprise yourself with how much you can accomplish in a very short period.

Learning to See focuses on Step 4, which implies establishing a future-state to guide you.

In the Forward, Womack and Jones commented that people skipped Step 4 (map your value streams). Today, I see people skipping straight to that step.

Let’s continue the context discussion from the Forward, then dig into common use of the value stream mapping tool..

“Find a change agent (how about you?)” is a really interesting statement. “How about you?” implies that the reader is the change agent. I suspect (based on the “change agents” discussed in Lean Thinking that the assumption was that the “change agent” is a responsible line leader. Pat Lancaster, Art Byrne, George Koenigsaecker were some of the early change agents, and were (along with their common thread of Shingijutsu) very influential in the tone and direction set in Lean Thinking.

Today, though, I see job postings like this one (real, but edited for – believe it or not- brevity):

Job Title: Lean Manager

Reports To: Vice President & General Manager of Operations

Summary:

Lead highly collaborative action-based team efforts to clean out, simplify and mistake-proof our processes and our strategic suppliers’ processes.

This includes using proven methodological approaches, applying our culture and providing our team with technology, best cross-industry practices and all other resources needed to attain ever higher levels of productivity and customer delight.

Essential Duties and Responsibilities:

Endlessly define, prioritize and present opportunities for applying AWO’s, GB/BB projects and other LEAN principles to our supply chain and customer deliverables.

Develop, plan and execute the plans as selected by the business leaders.

Train all team members (and other selected individuals) in LEAN principles and mechanisms to be LEAN and preferred by customers.

Document procedures/routines, training, team results/best practices and the like.

Coaches business team members in the practical application of the Lean tools to drive significant business impact.

Leads and manages the current state value stream process.

Develops and implements future state value stream processes.

[…]

Responsible for planning and assisting in the execution of various Lean transformation events targeted towards improving the business’s performance on safety, quality, delivery, and cost.

Focuses on business performance that constantly strives to eliminate waste, improve customer satisfaction, on-time delivery, reduce operating costs and inventory via the use of Lean tools and continuous improvement methodologies.

[…]

Acts as change agent in challenging existing approaches and performance.

Whew. With all of that, here is my question: What is the line leadership expected to do? In other words, what is left for them to do? And what, exactly, are they supposed to be doing (and how) during all of this flurry of activity?

While all of the “change agent” examples outlined in Lean Thinking (which, in turn, provides context for Learning to See), are line leaders, all too often the role of “change agent” is delegated to a staff member such as the above.

I believe it is entirely possible for a line-leader change agent to also be the “sensei” – Michael Balle’s The Lean Manager shows a fictional scenario that does just that.

But if your “sensei” is a staff technical professional, or an external consultant, the “change agent” function is separate and distinct, or should be.

Which leads me to the first question that is never asked:

Why Are You Doing This At All?

That question can be a pretty confrontational. But it is a question that often goes unasked.

This is especially true where “getting lean” is an initiative delegated to staff specialists, and not directly connected to achieving the strategic objectives of the business. In these cases, “Lean” is expressed as a “set of tools” for reducing costs.

I do not believe that “creating a crisis” is constructive, simply because when motivated by fear people tend to (1) panic and lose perspective and (2) tend to apply habitual responses, not creative ones. If there are high stakes at risk, creativity is not what you should expect.

On the other hand, a narrow and specific challenge that is set as Step Zero helps focus people’s attention and gives them permission not to address every problem all at once (which avoids paralysis and gridlock).

So, if I were to edit that list of steps, I’d change “Create a crisis” to “Issue a challenge to focus the effort” and move it to #1 or maybe #2 on the list. The “Find a sensei” then becomes a countermeasure for the obstacle of “We need AND WANT to do this, but don’t have enough experience.” (That assumption, in turn, implies a driving need to learn doesn’t it?)

These are appropriate roles for the “change agent” – and they are things that can only be effectively done from a position of authority.

Which brings us to back to Learning to See.

Beyond “Value-Added”

Someone, a long time ago, proposed that we categorize activities as “value-added” or “non-value-added.”

We say that a “value-added step” is “something the customer is willing to pay for.” A “non-value-added step” is anything else. Some non-value-added steps are necessary to advance the work or support the business structure.

While this analysis is fundamentally correct at the operational level, and works to get a general sense of what it possible, this approach can start us off on a journey to “identify and eliminate waste” from the process. (Not to mention non-productive debates about whether a particular activity is “value added” or not.)

Right away we are limited. The only way to grow the business using this approach is to use the newly freed up capacity to do something you aren’t doing now. But what?

If that decision hasn’t been made as a core part of the challenge, the leaders are often left wondering when the “lean initiative” will actually begin to pay – because they didn’t answer the “Why must we do this?” question from the beginning.

Without that challenging business imperative, the way people typically try to justify the effort is to:

- Analyze the process.

- Try to quantify the waste that is seen. This would be things like inventory, walking distance, scrap, etc. that are easily measurable. More sophisticated models would try to assign value to things like floor space.

- Add up the “proposed savings”

- Determine a return on the investment, and proceed if it is worth it.

The idea, then, would be to deliver those savings quickly with some kind of rapid improvement process.

This fundamental approach can be (and is) taken at all levels of the organization. I have seen large-scale efforts run by a team of consultants doing a rapid implementation of an entire factory over a timespan of a few weeks.

I have also seen that same factory six months later, and aside from the lines that were painted on the floor and the general layout changes, there was no other sign the effort had ever been undertaken. In this case, no matter how compelling the ROI, they didn’t get anywhere near it.

One of the tools commonly (ab)used for this process is value stream mapping.

This approach is SO common that if you search for presentations and training materials for value stream mapping on the web, you will find that nearly all of them show describe this process:

- Map your current state map.

- Identify sources of waste and other opportunities on the current state map.

- Depict those opportunities with “kaizen bursts” to show the effort you are going to make.

- Based on what opportunities you have identified, and your proposed kaizen bursts, develop the future state map to show what it will look like.

- Develop the new performance metrics for the future state.

- Viola – make the case to go for it.

Now – to my readers – think for a minute. Where are the “kaizen bursts” in Learning to See? They are on the current state map, right?

Nope.

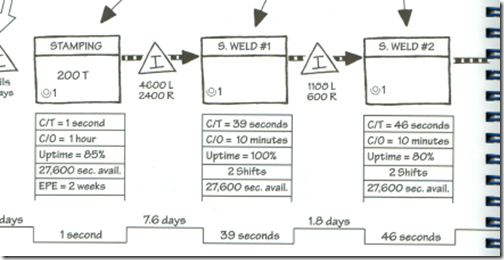

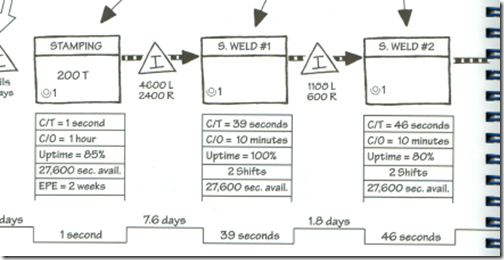

Here is the current state map on page 32:

If, on the other hand, I were to ask “What value do we wish we could create for our customers that, today, we cannot?” I open myself up to a host of possibilities, including creating a new value stream that currently doesn’t exist at all – using freed up resources, at essentially zero net cost (or at least heavily subsidizing the new effort).

Now I ask “What must I do to make these resources available to me?”

In the “find and eliminate waste” model, the staff-change agents are often responsible for the “lean plan.” Like the job description above, they are charged with convincing the leaders (who hired them!) that this all makes business sense.

A Manual for How to Meet a Challenge

In “Part III: What Makes a Value Stream Lean” (the green tab) there is a strong hint of the original intent in the second paragraph:

To reduce that overly long lead time from raw material to finished goods, you need to do more than just try to eliminate obvious waste.

This statement implies that the value stream mapper is dissatisfied with the current lead time, and has a compelling need to change it.

What you are looking for in the Future State is how must the process operate to get to the lead time reduction you must achieve.

For example, given a target lead time and a takt time, I can calculate the maximum amount of work-in-process inventory I can have and still be able to hit that objective.

I can look at where I must put my pacemaker process to meet the customer’s expectations for delivery.

Based on that, I can look at the turns I must create in the pull system that feeds it.

Based on that, I can calculate the maximum lot sizes I can have; which in turn, drives my targets for changeovers.

As I iterate through future state designs, I am evaluating the performance I am achieving vs. the performance I must achieve.

What is stopping me from making it work?

What must I change?

If something is too hard to change, what can I adjust elsewhere to get the same effect?

In the end, I have a value stream architecture that, if I can solve a set of specific problems, will meet the business need I started with.

This is my view on the fundamental difference between creating a generic “crisis” vs. stating a compelling performance requirement.

The process outlined in the book is to develop the future state, and then identify what is stopping you from getting there.

Of the eight KEY QUESTIONS FOR THE FUTURE STATE that are outlined in page 58, “What process improvements will be necessary for the value stream to flow as your future state design specifies?” is question #8.

It is the last thing you consider.

The kaizen bursts are not “What can we do?”

They are “What must we do?”

The first thing you consider is “What is the requirement?”

“What is the takt time?”

In other words, how must this process perform?

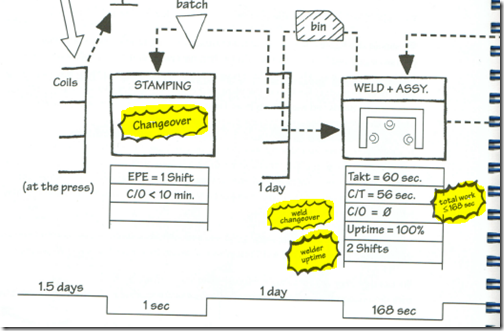

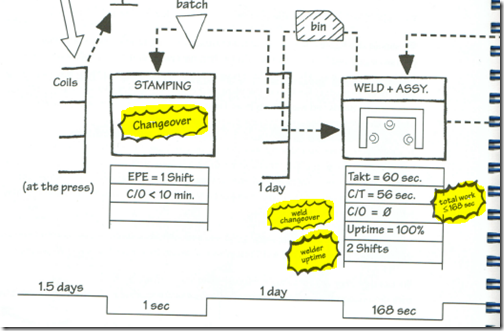

Here is a clip of the future state map from page 78:

The “bursts” are not “opportunities” but rather, they represent the things we have to fix in order to achieve the future state.

In Toyota Kata terms, they represent the obstacles in the way of achieving the target condition, just at a higher level.

What this is saying is “To achieve the future state we need to rearrange the work flow AND:

- Get the stamping changeovers down to 10 minutes or better.

- Get the weld changeovers to where we can do them within the takt.

- Get the welder uptime to 100%.

- Get the work content for weld + assembly down to under 168 seconds.”

These are the obstacles to achieving the performance we want from the future state value steam.

Notice that the stamping press only has an uptime of 85% on the current state map. There isn’t a corresponding kaizen burst for that – because, right now, it isn’t in the way of getting where we need to go. It might be an issue in the future, but it isn’t right now.

But if we were just “looking for waste” we might not see it that way, and spend a ton of time and resources fixing a problem that is actually not a problem at the moment.

Putting This Together

Thus, I suspect that Learning to See, like many books in the continuous improvement category, was intended for value stream leaders – managers who are responsible for delivering business results.

In my experience, however, most of the actual users have been staff practitioners. Perhaps I should use the 2nd person here, because I suspect the vast majority of the people reading this are members of that group.

You are a staff practitioner if you are responsible for “driving improvement” (or a similar term) in processes you are not actually responsible for executing on a daily basis. You are “internal consultants” to line management.

Staff practitioners are members of kaizen promotion offices. They are “workshop leaders.” They are “continuous improvement managers.” The more senior ones operate at the VP and Director level of medium and large size companies.

No matter what level of the organization, you are kindred spirits, for most of my post-military / pre-consulting career has been in this role.

The people who actually read and study books like Learning to See are staff practitioners.

This creates a bit of a problem, because Learning to See is very clear that the responsible manager should be the one actually building the value stream map. But often, that task is delegated to the staff practitioner.

“Map this value stream, and please present your findings and recommendations.” If you have gotten a request or direction like that, you know what I am talking about. Been there, done that.

In my personal experience, although it gave me valuable experience studying process flows, I can honestly say that relatively few of those proposed “Future States” were actually put into practice.

The one that I vividly remember that was put into practice happened because, though I was a kaizen promotion office staffer, I had start-up direct responsibility for getting the process working, including de-facto direct reports. (That is a different story titled “How I got really good at operating a fork lift”)

Into 2013

Today we see Toyota Kata quickly gaining popularity. The Lean Bazaar is responding, and “coaching” topics are quickly being added to conference topics and consulting portfolios.

I welcome this because it is calling attention to the critical people development aspect that distinguishes the Toyota Management System from the vast majority of interpretations of “lean” out there.

But make no mistake, it is easy to fall into the tools trap, and the Lean Bazaar is making it easier by the way it positions its products.

Just as value stream mapping isn’t about the maps, establishing an improvement culture isn’t about the improvement boards, or the Kata Kwestions.

It is about establishing a pervasive drive to learn. In that “lean culture,” we use the actual process as a laboratory to develop people’s improvement skills. We know that if we do the right job teaching and practicing those skills, the right people will do the right things for the process to get better every day. Which is exactly what the title of Learning to See says.