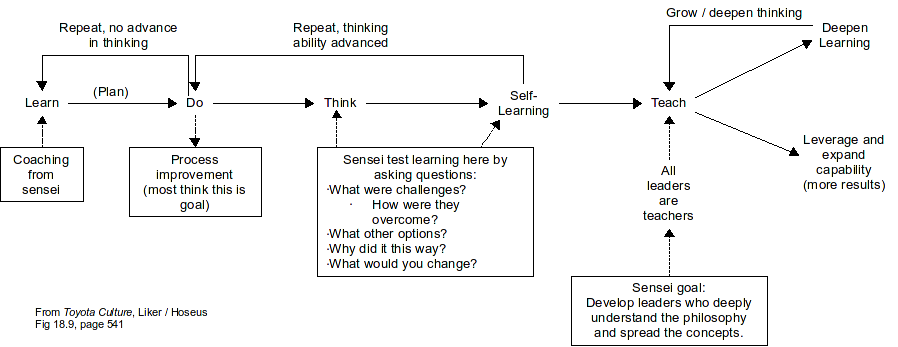

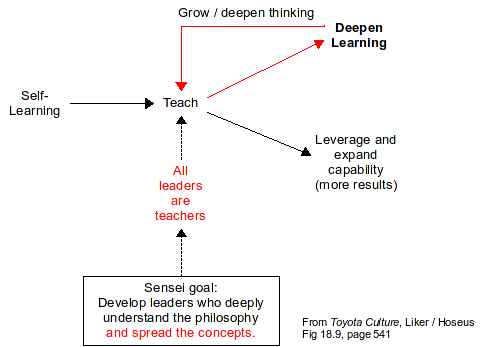

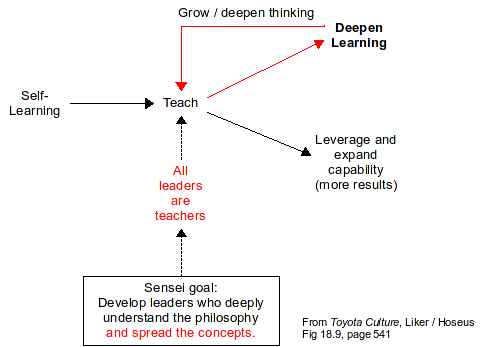

In a previous post, I talked about Steven Spear’s observation about how a sensei saw a process and the problems. Jeffery Liker, Mike Hoseus and David Meier have done a good job capturing how a sensei teaches and summed it up in a diagram in the book Toyota Culture . (for those of you following at home, the diagram is figure 18.9 on page 541).

. (for those of you following at home, the diagram is figure 18.9 on page 541).

I want to dissect this model a bit and share some of the thoughts I had.

This is the whole diagram:

This diagram strikes me in a couple of ways.

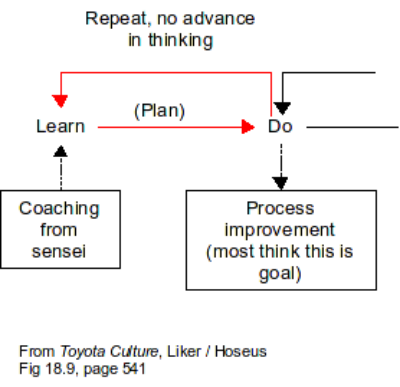

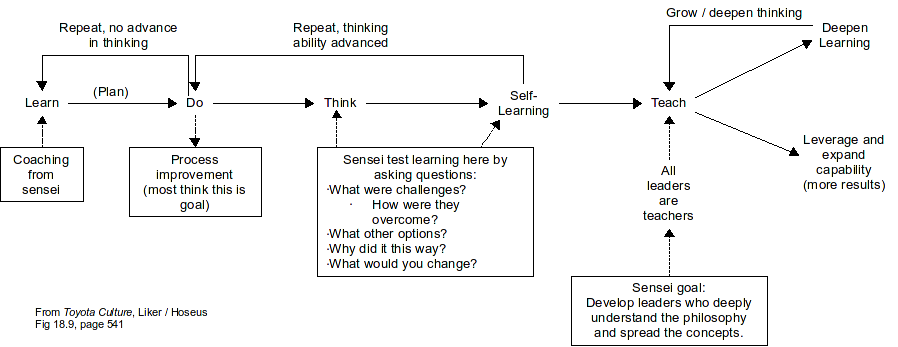

Let’s zoom in to the left hand side.

I’m calling the part I’ve highlighted in red the “sensei do-it-loop.” That is, the sensei says “Do this,” the students do it, then the sensei says “Now, do this.” Repeat.

While this first loop is the starting point, all too often, it is also the ending point.

And in this loop, process improvement actually happens, everybody applauds at the Friday report-out. The participants may even prepare a summary of key learning points. And perhaps, as follow up, they will apply the same tools in a similar situation. (As much as I hope for this outcome, though, it doesn’t happen as often as I would like.)

A lot of consulting engagements go on this way for many years. Some go decades. I am sure processes improve, and I am equally sure it is very lucrative for those consultants. But even if they are extraordinarily skilled at seeing improvement opportunities and pointing them out, these consultants are not sensei in the meaning of this diagram. That distinction is made clear in the next section.

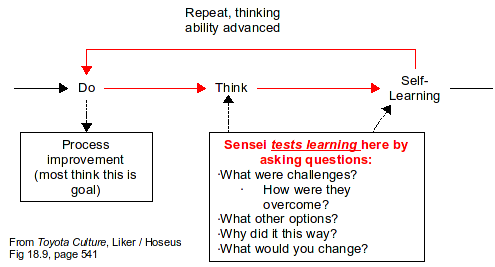

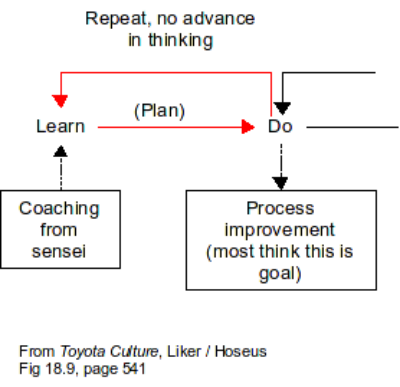

This is where the learning happens.

I have highlighted the learning loop in red.

The sensei is primarily interested in developing people so that they can see the opportunities and improve the processes themselves. He wants to move them along the continuum from “Do” to “Think” so that they understand, not only this process, but learn how to think about processes in general. When the sensei asks the questions, he is forcing people to articulate their understanding to him. He is really saying “teach me.” In this way he pushes people to deepen their own understanding from “think it through” to “understand it well enough to explain to someone else.”

Think about Taiichi Ohno’s famous “chalk circle.” The “DO THIS” was “stand here and watch the process.” He had seen some problem, and wanted the (hapless) manager to learn to see it as well. Ohno didn’t point it out, he just directed their eyes. His “test” was “What do you see?,” essentially repeated until the student “got it.”

The second leap here is from “Think” to “Self Learning.” At this point, people have learned to ask the questions of themselves, and of each other. So when he asks his questions, the sensei is not merely interested in the answers as a CHECK of learning, he is also teaching people the questions.

These questions are also a form of “reflection.” They are a CHECK of what was planned vs. what was done; and what was intended vs. what was accomplished. The ACT in this case is to think through the process of improvement itself, not simply what was improved.

Until people learn to do this, “Self Learning” does not occur, and the team is forever dependent on external resources (the sensei, consultants) to push themselves.

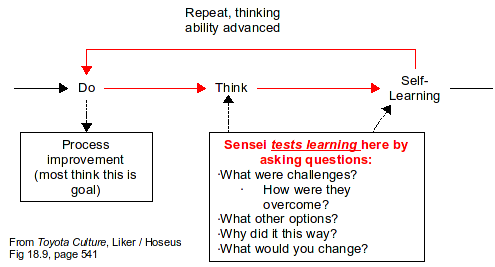

But the sensei is not through. Once people have a sense of self-learning, the next level is capability to teach others. “All leaders as teachers.”

Someone, I don’t know who, once said that teaching is the best learning. I can certainly say that my own experiences back this up. My greatest ah-ha moments have come when I was trying to explain a concept, not when it was being explained to me.

I would contend, therefore, that a true sensei is not so much one who has mastered the subject, but rather one who has mastered the role of the eternal student. It is mastery in learning that sets apart the very best in a field.

Thus the sensei‘s work is not done until he has imparted this skill to the organization.

As the leaders challenge their people to thoroughly understand the process, the problems, to explore the solutions, so do the leaders challenge themselves to understand as well.

They test their people’s knowledge by asking questions. They test the process knowledge of their people by expecting their people to teach them, the leaders, about the process. Thus, by making people teach, they drive their people to learn in ways they never would have otherwise. The leader teaches by being the student. The student learns by teaching. And the depth of skill and knowledge in the entire organization grows quickly, and without bound.

So Here Is Your Question:

If your organization is typical of most who are treating “lean” as something to “implement” you have the following:

You have a cadre of technical specialists. Their job, primarily, is to seek out opportunities for kaizen, assemble the team of people, teach them the mechanics, then guide them through making process improvements that hit the targets. This is often done over the course of 5 days, but there are variations on this. The key point is that the staff specialists are delegated the job of evangalizing “lean” and teaching it to the people on the shop floor.

Again, if it is typical, there is some kind of reporting structure up to management. How many kaizens have you run? What results have you delivered? How many people have been trained? Managers show their commitment and support by participating in these events periodically, by attending the report-outs, and by paying attention to these reports and follow-up of action items.

Now take what you have just read, and ask yourselves – “Are we getting beyond the first loop, or are we forever just implementing what is in the books?”

How are you reinforcing the learning?

Who is responsible to learn by teaching?

I’ll share a secret with you about a recent post. When Paul and I took Earl through his own warehouse that Friday night, neither of us had been in there before. While I can’t speak for Paul, everything I knew about warehouse operations and crossdocks, I learned from Earl. I didn’t teach him anything that night. Paul and I did, however, push him to teach us, and in doing so, he learned a great deal.