Following on from the buzz created by the last couple of posts, I would like to go back in time a bit.

In 2005 Steven Spear wrote a working paper called “Why General Motors Lost and Toyota Won.” A reader can clearly the see emerging themes that were developed into his book Chasing the Rabbit .

Spear talks about the leverage of “operationally outstanding” in changing the game, the capabilities he sees in “operationally outstanding” organizations, then “Failure Modes at Becoming Toyota Like.”

I would like to dwell a bit on these failure modes, and reflect a little on what they look like.

Failure Mode 1: Copy Lean Tools Without Making Work Self Diagnostic

So what does “self diagnostic” mean?

For something to be “self diagnostic” you need two pieces of information:

- What is supposed to happen.

- What actually happens.

Then you need some mechanism that compares the two and flags any difference between them. This sounds complicated, but in reality, it isn’t.

Let’s look at a common example: At the most basic level, this is the purpose of 5S.

5S as a Self Diagnostic Tool

In 5S, you first examine the process and seek to understand it. Then, applying your best understanding, you decide what is necessary to perform the process, and remove everything else. Applying your best understanding again, you seek to locate the items where they would be used if the process goes the way you expect it to.

You improve the self-diagnostic effect by marking where things go, so it immediately clear if something is missing, out of place, or excess.

Then you watch. As the process is carried out, your “best understanding” is going to be tested.

Can it be done with the things you believed are necessary? If something else is required, then you have an opportunity to improve your understanding. Get that item determine where it is used, and carry out the operation. But go a little deeper. Ask why you didn’t realize this was needed when you examined the process. Challenge your process of getting that initial understanding and you improve your own observation skills.

Is everything you believed is necessary actually used? If not, then you have another opportunity to improve your understanding. Is that item only used sometimes? When? Why? Is it for rework or exceptions? (see failure mode #2!) Why did you believe it was necessary when you did your initial observation?

Does something end up out of place? Is it routinely used in a place other than where you put it? This is valuable information if you now seek to understand how the process is different from what you expected.

Now think about the failure mode: What does fake-5S look like? What is 5S without this thinking applied?

How do you “do” 5S?

Look long and hard if you are trying to audit your way into compliance rather than using it as a diagnostic for your understanding of your process.

Though the jargon “self diagnostic” sounds academic, we have all talked about visual controls “distinguishing the normal from the abnormal” or other similar terms. It is nothing new. What makes this a failure mode is that people normally don’t think it is that important when Spear cites a mountain of evidence (and I agree) that this is critical to success. You can only solve the problems you can see.

Another Example: Takt Time

What is takt time? Before you whip out your calculators and show me the math, step back and ask the core question of “What it is” rather than “how to calculate it.” What is it?

Takt time is part of a specification for a process – it defines what should be happening. By setting takt time you are saying “IF our process can routinely cycle at this interval, then we can meet our customer’s demand. Takt time defines both part of a “defect free” outcome of your work cycle as well as a specification for process design.

Then you apply your very best knowledge of the process steps and sequence and set out a work cycle which you believe can be accomplished within the takt. It becomes self-diagnostic when you check, every time if the actual work cycle was the same as the intended work cycle. An easy way to check is to compare the actual time with the designed time.

In Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System, Spear cites an example of seat installation.

At Toyota’s plants, […] it is instantly clear when they deviate from the specifications. Consider how workers at Toyota’s Georgetown, Kentucky, plant install the right-front seat into a Camry. The work is designed as a sequence of seven tasks, all of which are expected to be completed in 55 seconds as the car moves at a fixed speed through a worker’s zone. If the production worker finds himself doing task 6 (installing the rear seat-bolts) before task 4 (installing the front seat-bolts), then the job is actually being done differently than it was designed to be done, indicating that something must be wrong. Similarly, if after 40 seconds the worker is still on task 4, which should have been completed after 31 seconds, then something, too, is amiss. To make problem detection even simpler, the length of the floor for each work area is marked in tenths. So if the worker is passing the sixth of the ten floor marks (that is, if he is 33 seconds into the cycle) and is still on task 4, then he and his team leader know that he has fallen behind.

On this assembly line, time is used, not so much to pace the work, but as a diagnostic tool to call out instances when the work departs from what is intended – or in simpler terms, when there is a problem.

All of this has been about checking that the process is being carried out as expected. But, bluntly, the customer really doesn’t give a hoot about the process. The customer is interested in the output. How do you know that the output of your process is actually helping your customer?

To know that you first have to be really clear on a couple of things:

- Who your customer actually is.

- What value do you provide to that customer?

Put another way, can you establish a clear, unambiguous specification of what a defect free outcome is for each supplier-customer interface in your process? Can you follow that trap line of supplier-customer interfaces down to the process of delivering value to your paying customers?

To make this self-diagnostic, though, you have to not only specify (what should be happening), you have to check (what is actually happening), and you have to do it every time.

So poka-yoke (mistake proofing) is a way to verify process steps. Other mistake proofing will detect problems with the outputs. All are (or should be) designed to diagnose any problems and immediately halt the process or, at the very least, alert someone.

The theme that is emerging here is the concept of PLAN-DO and CHECK, with the CHECK being thoroughly integrated into the process itself, rather than a separate function. (Not that it can’t be, but it is better if CHECK is continuous.)

The Supply Chain

I was walking through the shop one afternoon and spotted an open bundle of steel tube – about half of them remaining. They used kanban to trigger re-order. The rule of kanban is that the kanban card is pulled and placed in the post when the first part is consumed. To make this clear, they literally attached the kanban to the bands with a cable tie. Thus, breaking the band would literally release the kanban. Simple, effective.

But, though this bundle had been opened, there was the kanban card still attached to the (now broken) banding. It was lurking at the base of the pallet, but visible.

I went and got the supervisor, and told him that “You are going to have a shortage of 4×5 tube on Wednesday, and it is your fault. Would you like to know why?” I guess I should point out that I had a pretty good relationship with this guy, so he knew I was playing him a little. Then I just said “Look, and tell me what you see.”

It took a few seconds, but he saw the kanban, said “Argh” and started to pick it up to put into the post. I stopped him and asked if it was his responsibility to do that. No, it was the welder’s responsibility. “Then you should take a minute with him, and do what I just did with you.”

Then I asked him how often the kanban cards were collected. (I knew, I wanted to check that he knew.) “Daily, about 1 pm.”

“How often do you walk by here every day?” He said at least twice, in the morning and right after lunch. “So all you need to do is take a quick glance as you walk by, twice a day, and you will always get that kanban into the post before 1pm.”

He did, and their periodic shortages dropped pretty much to zero.

Why?

First, the system was set up JIT. We knew the expected rate of use of that part. We knew the supplier’s lead time and delivery frequency. We knew the bundle size. MATH told us the minimum number of kanban cards that would need to circulate in this loop to ensure the weld cell never ran out… unless one of the inputs was wrong or unless the process operated differently than we expected.

We also knew that, given the rate of consumption, how many bundles should be in the shop at any given time, and we had space market out for just that amount. Thus, we could tell immediately if something was received early, or if our rate of consumption fluctuated downward. (Because a pallet would arrive, but there would be no place to put it.)

We could have just had a Team Member come by once a day and check if a bundle had been opened, and send an order to replenish it. We could have been even more sophisticated and just set up a barcode scan that would trigger a computer order.

But if we had set up the process that way, how could the Supervisor distinguish between “Ordered” or “Not Ordered?” It was that stray out-of-place kanban card that told him.

Thus, physical kanban cards, physically attached to the materials, represent a self-diagnostic check. If the card is there, then that container should be full. Quick to check. If the container is not full, there should be no card. Quick to check. If a container arrives with no card, it was not properly ordered and is likely excess (or at least calls for investigation). Quick to check. The physical card, the seeming crude manual operation, provides cross-checks…self-diagnosis… simply and cheaply in ways that few automated systems replicate.

Thus, physical kanban cards, physically attached to the materials, represent a self-diagnostic check. If the card is there, then that container should be full. Quick to check. If the container is not full, there should be no card. Quick to check. If a container arrives with no card, it was not properly ordered and is likely excess (or at least calls for investigation). Quick to check. The physical card, the seeming crude manual operation, provides cross-checks…self-diagnosis… simply and cheaply in ways that few automated systems replicate.

So far these have all been manufacturing examples. But Spear is clear that all work is self-diagnostic, not just manufacturing.

What non-manufacturing work fits into this model?

(Hint: All of it.)

What about a project plan? Though in reality, most project plans don’t. Read Critical Chain by Goldratt to understand the difference – and produce and manage project plans that are much more likely to finish on time.

What about a sales plan? Do you predict your monthly sales? Do you check to see if week 1 actual sales deviated from what was expected? Do you plan on activities that you believe will hit your sales targets? Which customers are you calling on? What do you predict they will do? (Which tests how well you really know them.) Do you actually call on those customers? Do they need what you thought they would? Or do you learn something else about them? (Or do you make a best guess “forecast” and wait for the phone to ring?)

Once you have a sales plan, do you put together a manufacturing and operations plan which you believe will match production to sales? How much variation do you expect to accumulate between production and sales over the course of that plan? Do you put alarm thresholds on your finished goods or your backlog levels that would tell you when that predicted variation has been exceeded?

How do you (and how often do you) compare actual sales (volume, models, and revenue) against the plan? Do you know right away if you are off plan? How long will you tolerate being off plan before you decide that something unexpected is happening? Is there a hard trigger point already set out for that? Or do you let the pain accumulate for a while?

A lot of companies were caught totally by surprise a few months ago when their sales seemed to fall off a cliff. Question: Did you have rising inventory levels before that? Was there a threshold that forced attention to something unexpected? Or did you increasingly tolerate and normalize deviance from your intended business plan?

At the next levels up – you have a business plan of some kind. You have financial targets. Do you have specific actions you plan to take at specific times? Do you check if those actions were actually taken? Do those actions have some kind of predicted outcome associated with them? Do you check if the actual outcome matches what you predicted? If you just “try something to see what happens” you might learn, but you might not. If you predict, then try to see IF it happens, you are more likely to gain more understanding from that experience.

When you design a product, do you have performance specifications? Do you test your design(s) against those performance specifications? Do you do that at every stage, or just at the end?

When you say “We need training” have you first specified what the work process is? Have you studied the situation and determined that people do not have the skills or knowledge to do the job? Have you specified what those skills are?

Have you developed the training to specifically develop those skills? Do you have a way to verify that people got the skills required? Do you check if, now, they can perform the work that they could not perform before? If you didn’t do the last, why did you “train” them at all? How do you know it was not just entertainment?

“Management Is Prediction”

This quote, attributed to W. Edwards Deming, really sums up what this is about. By specifying an outcome – “defect free” (which implies you know that is), within a certain time; and by specifying the process steps; you are predicting the outcome.

“If we do these things, in this sequence, it should require this amount of time, and produce this result.”

Then do it, and check:

Does what you really had to do reflect the tasks you thought would be required?

Does the order you really did them in reflect what was in the plan?

Does the time required reflect the time you planned on?

Did it produce the intended result?

Building those checks into the process itself makes it self-diagnostic.

Try This

Go study a process, any process. Just watch. Constantly ask yourself:

How does this person know what to do?

How does this person know if s/he is doing it right?

What alerts this person if s/he makes a mistake?

How does this person know s/he succeeded?

If there are clear, unambiguous answers right in front of you – without research, without requiring vigilance or luck on the part of the Team Member, then you probably have something approaching self-diagnostic work. Likely, you don’t. If that is the case, don’t say you are “doing lean.” You are only going through the motions.

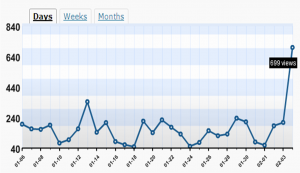

Needless to say “Remembering Nummi” got some legs under it.

Needless to say “Remembering Nummi” got some legs under it.