In the world of science, great discoveries simplify our understanding. When Copernicus hypothesized that everything in the universe does not revolve around the Earth, explaining the motions of things in the sky got a lot easier.

In the world of science, great discoveries simplify our understanding. When Copernicus hypothesized that everything in the universe does not revolve around the Earth, explaining the motions of things in the sky got a lot easier.

In general, I have found that if something requires a great deal of detail to explain the fundamentals, there is probably another layer of simplification possible.

Even today, a lot of authors explain “lean manufacturing” with terms like “a set of tools to reduce waste.” Then they set out trying to describe all of these tools and how they are used. This invariably results in a subset of what the Toyota Production System is all about.

Sometimes this serves authors or consultants who are trying to show how their process “fills in the gaps” – how their product or service covers something that Toyota has left out. If you think about that for a millisecond, it is ridiculous. Toyota is a huge, successful global company. They don’t “leave anything out.” They do everything necessary to run their business. Toyota’s management system, by default, includes everything they do. If we perceive there are “gaps” that must be filled, those gaps are in our understanding, not in the system.

So let me throw this out there for thought. The core of what makes Toyota successful can be expressed in four words:

Management By Hypothesis Testing

I am going to leave rigorous proof to the professional academics, and offer up anecdotal evidence to support my claim.

First, there is nothing new here. Let’s start with W. Edwards Deming.

Management is prediction.

What does Deming mean by that?

I think he means that the process of management is to say “If we do these things, in this way, we expect this result.” What follows is the understanding “If we get a result we didn’t expect, we need to dig in and understand what is happening.”

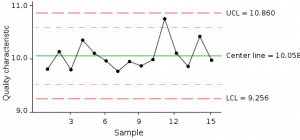

At its most basic level, the process of statistical process control does exactly that. The chart continuously asks and answers the question “Is this sample what we would expect from this process?” If the answer to that question is “No” then the “special cause” must be investigated and understood.

At its most basic level, the process of statistical process control does exactly that. The chart continuously asks and answers the question “Is this sample what we would expect from this process?” If the answer to that question is “No” then the “special cause” must be investigated and understood.

If the process itself is not “in control” then more must be learned about the process so that it can be made predictable. If there is no attempt to predict the outcome, most of the opportunity to manage and to learn is lost. The organization is just blindly reacting to events.

Here is another quote, attributed to Taiichi Ohno:

Without standards, there can be no kaizen.

Is he saying the same thing as Deming? I think so. To paraphrase, “Until you have established what you expect to do and what you expect to happen when you do it, you cannot improve.” The quote is usually brought up in the context of standard work, but that is a small piece of the concept.

So far all of these things relate to the shop floor, the details. What about the larger concepts?

What is a good business strategy? Is it not a defined method to achieve a desired result? “If we do these things, in this way, at these times, we should see this change in our business results.” The deployment of policy (hoshin planning) is, in turn, multiple layers of similar statements. And each of the hoshins, and the activities associated with them, are hypothesized to sum up to the whole.

The process of reflection (which most companies skip over) compares what was planned with what was actually done and achieved. It is intended to produce a deeper level of learning and understanding. In other words, reflection is the process of examining the experimental results and incorporating what was learned into the working theory of operation, which is then carried forward.

Sales and Operations Planning, when done well, carries the same structure. Given a sales and marketing strategy, given execution of that strategy, given the predicted market conditions, given our counters to competitor’s, we should sell these things at this time. This process carries the unfortunate term “forecasting” as though we are looking at the weather rather than influencing it, but when done well, it is proactive, and there is a deliberate and methodical effort to understand each departure from the original plan and assumptions.

Over Deming’s objections, “performance management” and reviews are a fact of life in today’s corporate environment. If done well, then this activity is not focused on “goals and objectives” but rather plans and outcomes, execution and adjustment. In other words, leadership by PDCA. By contrast, a poor “performance management system” is used to set (and sometimes even “cascade”) goals, but either blurs the distinction between “plans” (which are activities / time) and “goals” which are the intended results… or worse, doesn’t address plans at all. It gets even worse when there are substantial sums of money tied to “hitting the goals” as the organization slips into “management by measurement.” For some reason, when the goals are then achieved by methods which later turn out to be unacceptable, there is a big push on “ethics” but no one ever asks for the plan on “How do you plan to do that?” in advance. In short, when done well, the organization manages its plans and objectives using hypothesis testing. But most, sadly, do not.

Let’s look at another process in “people management” – finding and acquiring skills and talent, in other words, hiring.

In average companies, someone needing to hire someone puts in a “requisition” to Human Resources. HR, in turn, puts that req out into the market by various means. They get back applicants, screen them, and turn a few of them over to the hiring manager to assess. One of them gets hired.

What happens next?

The new guy is often dropped into the job, perhaps with minimal orientation on the administrative policies, etc. of the company, and there is a general expectation that this person is actually not capable of doing the work until some unspecified time has elapsed. Maybe there is a “probation period” but even that, while it may be well defined in terms of time, is rarely defined in terms of criteria beyond “Don’t screw anything up too badly.”

Contrast this with a world-class operation.

The desired outcome is a Team Member who is fully qualified to learn the detailed aspects of the specific job. He has the skills to build upon and need only learn the sequence of application. He has the requisite mental and physical condition to succeed in the work environment and the culture. In any company, any hiring manager would tell you, for sure, this is what they want. So why doesn’t HR deliver it? Because there is no hypothesis testing applied to the hiring process. Thus, the process can never learn except in the case of egregious error.

If we can agree that the above criteria define the “defect free outcome” of hiring, then the hiring process is not complete until this person is delivered to the hiring manager.

Think about the implications of this. It means that HR owns the process of development for the skills, and the mental and physical conditioning required of a successful Team Member. It means that when the Team Member reports to work in Operations, there is an evaluation, not of the person, but of the process of finding, hiring, and training the right person with the right skills and conditioning.

HR’s responsibility is to deliver a fully qualified candidate, not “do the best they can.” And if they can’t hire this person right off the street, then they must have a process to turn the “raw material” into fully qualified candidates. There is no blame, but there are no excuses.

Way back in 1944, the TWI programs applied this same thinking. The last question asked on the Job Relations Card is “Did you accomplish your objective?” The Job Instruction card ends with the famous statement “If the worker hasn’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught.” In other words, the job breakdown, key points and instruction are a hypothesis: If we break down the job and emphasize these things in this way, the worker will learn it over the application of this method. If it didn’t work, take a look at your teaching process. What didn’t you understand about the work that was required for success?

I could go on, but I have yet to find any process found in any business that could not benefit from this basic premise. Where we fail is where we have:

- Failed to be explicit about what we were trying to accomplish.

- Failed to check if we actually accomplished it.

- Failed to be explicit about what must be done to get there.

- Did something, but are not sure if it is what we planned.

- Accepted “problems” and deviation as “normal” rather than an inconsistency with our original thinking (often because there was no original thinking… no attempt to predict).

As countermeasures, when you look at any action or activity, contentiously ask a few questions.

- What are we trying to get done?

- How will we know we have done it?

- What actions will lead to that result?

- How will we know we have done them as we planned?

And

- What did we actually do?

- Why is there a difference between what we planned and what we did?

- What did we actually accomplish?

- Why is there a difference between what we expected and what we got?

The short version:

- What did we expect to do and accomplish?

- What did we do and get?

- Why is there a difference?

- What are we doing about it?

- What have we learned?

In the world of science, great discoveries simplify our understanding. When Copernicus hypothesized that everything in the universe does not

In the world of science, great discoveries simplify our understanding. When Copernicus hypothesized that everything in the universe does not  At its most basic level, the process of statistical process control does exactly that. The chart continuously asks and answers the question “Is this sample what we would expect from this process?” If the answer to that question is “No” then the “special cause” must be investigated and understood.

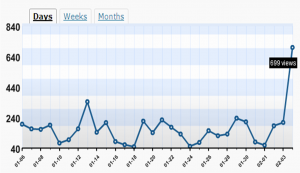

At its most basic level, the process of statistical process control does exactly that. The chart continuously asks and answers the question “Is this sample what we would expect from this process?” If the answer to that question is “No” then the “special cause” must be investigated and understood. Needless to say “Remembering Nummi” got some legs under it.

Needless to say “Remembering Nummi” got some legs under it.