by Hank C. Andersen

Not many years ago there was a CEO so exceedingly fond of finding the right strategy that he spent all of his money on consultants to tell him what the strategy should be.

One day there came two consultants and they said they could craft the most magnificent strategy imagianable. Not only would it solve all of the problems, and produce great prosperity and profitability, but it had an added feature: It would make no sense to anyone not qualified to be in his job.

“This would be just the strategy for me,” thought the CEO. “If I adopted it, then I would be able to discover which managers in my company are unfit for their posts. I could tell the ones I can trust from those who must be fired. Yes, I must have this strategy,” and he paid the consultants a large sum of money to start work at once.

The consultants set up their laptops and pretended to produce all sorts of presentations, though the presentations were actually jargon, buzzwords and gibberish. They demanded all sorts of information about customers, sales, products, and market sectors while they worked their PowerPoint far into the night.

“I would like to know how these consultants are getting on with the strategy,” the CEO thought, but he felt uncomfortable when he remembered that those who were unfit for their position would not be able to understand it. It couldn’t be that he doubted himself, yet he thought he would rather send someone else to see how things are going.

The whole staff knew about the strategy’s peculiar power, and all were impatient to find out how stupid everyone else was.

“I’ll send the President of my largest division to the consultants,” the CEO decided. “He’ll be the best one to tell me how the strategy works, for his division is always highly profitable, and no one does the job better.”

So the Division President went to the room where the two consultants sat working away at their Buzz Words PowerPoint presentations.

“Heaven help me,” he thought, as he studied the screen, “but this makes no sense at all. If we follow this strategy we shall surely send our customers to our competitors.” But he did not say so.

Both of the consultants begged him to be so kind as to come near to approve the details of the strategy, the nuances of the implementation plans. They pointed to boxes, arrows, circles, and buzzwords, but as hard as the poor Division President looked, he could not understand anything because there was nothing that could be understood.

“Can it be that I am a fool? I could have never guessed it, but not a soul must know. If I question the strategy, I will reveal myself to be unfit, and surely be fired,” he thought.

“Don’t hesitate to tell us what you think of it,” said the consultants.

“Oh it is amazing, I can clearly see how this will streamline our operations and increase our profit margins. I will be sure to tell the CEO that this strategy must be adopted, without question, across the company.” And so he did.

The consultants at once asked for more money and more data so they could add to the details, and continued to pump out more and more slides of management buzzwords.

The CEO asked his Chief Operating Officer to see how the work progressed, and how soon it would be ready. The same thing happened to him as had happened to the Division President. He looked and looked, but as there was nothing that made sense, he could not understand it.

“Isn’t this a magnificent strategy?” the consultants asked him as they displayed and described their back-up slides.

“I know I am not stupid,” the COO thought, “so it must be that I am not qualified for my job, for this strategy makes no sense to me.”

“That’s strange, I know I have been a successful business leader. I must not let anyone find out.” So the COO praised the strategy that he could not understand. He declared it to be almost ready for deployment across the entire company. To the CEO he said, “It is magnificent, and anyone who questions or challenges it must be fired immediately.”

All the company was talking of this splendid strategy, and the CEO wanted to see it for himself while it was still on the consultants’ laptops. Attended by the Board of Directors, among whom were his two old trusted officials, the ones who had seen the consultants, he set out to find the consultants hard at work on their PowerPoint slides.

“It is amazing,” said the COO and Division President. “Just look, sir, what brilliance! What design!” They pointed to boxes and arrows each supposing the others understood what it all meant.

“What is this?” thought the CEO. “I can’t understand any of this. This is terrible.”

“Am I a fool? What if the Board of Directors finds out that I cannot understand this?”

“Oh – it is brilliant,” he said, “It has my complete approval.”

The entire Board and Staff stared and stared. Nobody could understand more than anyone else, but they all joined the CEO in exclaiming, “Oh it is brilliant!” and they advised the CEO to deploy the strategy across the company in a great kickoff and rollout process.

The CEO gave each of the consultants a company pin to wear, and paid their final fees plus a bonus.

Before the kickoff, the consultants sat up all night and drank two pots of coffee to show how busy they were finishing the CEO’s new strategy. They printed handouts and workbooks, posters and training materials. And at least they said, “Now the strategy is ready for the kickoff.”

Then the CEO came with all his staff, the Division Presidents, and the Board of Directors to see the consultants’ presentation.

The consultants went through each slide, pointing out how the new strategy revolved around empowering the organization to achieve market positioning by creating synergy through focus on cultivating agile B2B relationships with key customers utilizing the talent pool. This would be done by incorporating A.I. to embrace the vital few in order to maximize the effectiveness of the e-commerce solutions. Further, costs would be reduced and product quality enhanced through embracing a holistic approach, continuously monitoring performance, and fostering a culture of continuous improvement in order to optimize production processes through operational efficiency measures, streamlining supply chain management, and technology integration. And on and on they want, explaining nothing at all as though it had profound meaning.

During the break, the CEO asked his staff what they thought. “It is a find strategy,” they all agreed. “It is lightweight, robust, and will give us great focused solutions.”

“This strategy is brilliant,” they all agreed, as they flipped through the colored brochures describing everything.

And with that, they agreed they must post the entire presentation on the corporate interwebz for everyone to see.

And so they did. And the Middle Managers all agreed this this, indeed, was a remarkable strategy. When one of them dared to question it, he was fired immediately, for he obviously was incompetent.

In the coming weeks, the CEO presided over all-hands meetings at each site in the company. Then, at one of the meetings, a forklift driver said, “But this makes no sense at all, It is just a bunch of management gibberish.”

“Have you ever heard such an ignorant comment?” said the worker’s manager. But the others started to whisper to one another… “But the strategy makes no sense.”

As the word spread by social media, email, and even phone calls, soon everyone in the company was saying, “The strategy makes no sense.”

The CEO shivered, for he suspected they were right, but he thought, “We must deploy this strategy,” and had his staff report weekly on implementation progress on a strategy that was nothing at all.

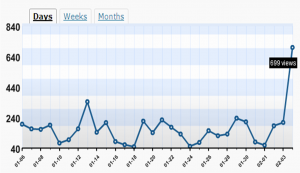

Needless to say “Remembering Nummi” got some legs under it.

Needless to say “Remembering Nummi” got some legs under it.