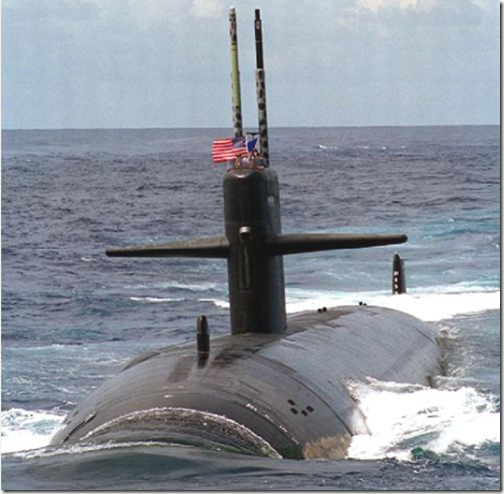

I’ve been parsing Turn the Ship Around to better understand David Marquet’s message from his experience as captain of the USS Santa Fe (SSN 763), a Los Angeles Class nuclear powered attack submarine.

And I’ve been promising to link his concepts back to Toyota Kata. So now I’m going to try to do that.

You can see part of the back story by reviewing my original post and watching the video here: /2013/11/06/creating-an-empowered-team/

Here is the rest of the back story.

Capt. Marquet was originally programmed to take command of the USS Olympia (SSN 717) which is also a Los Angeles Class submarine.

Except that the “improved” versions of Los Angeles Class submarines, from SSN 751 onwards, are really a completely different design. In any other navy, those later versions would be a different class of ship.

The Olympia is the earlier version, the Santa Fe is much newer.

The Olympia looks like this:

This is the Santa Fe:

The obvious difference is the (lack of) dive planes on the sail. The Olympia doesn’t have those forward missile tubes. The sonar is different. The reactor and power plant is different.

Capt Marquet’s problem was that he was ordered to take command of the Santa Fe at the last minute, after studying everything about the Olympia for an entire year.

Traditionally, a (US Navy) submarine captain’s credibility and authority is anchored on him as a technical expert on every aspect of what the machine can, and cannot, do. This is the foundation for him giving good orders to the officers, NCOs and crew. In practice, the command model is that the ship is a machine with one brain and many hands.

A lot of businesses run the same way.

Except that Captain Marquet wasn’t a technical expert. On the first cruise he gave an order to do something that the Santa Fe couldn’t do, the Navigation Officer knew it wasn’t possible, and passed the order along anyway “Because the Captain told him to.” That is where the little video in the previous post picks up.

OK, that’s the back story.

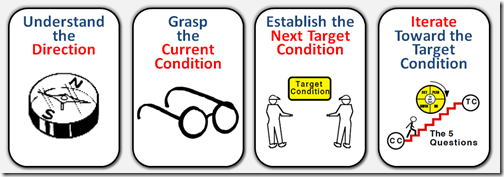

Developing Leaders with the Improvement Kata

Challenge and Direction

Like in the Improvement Kata, Capt Marquet got a clear challenge and direction from his boss, Commodore Kenny. The performance of the Santa Fe was sub-standard. They were doing poorly on inspections, making mistakes, morale was poor, reenlistment (an indicator of morale) was the worst in the fleet. Officers were resigning. Capt Marquet’s task as the new Captain was to get that performance up to where the Navy needed it to be.

Grasp the Current Condition

Chapters 4, 5 and 6 of Turn the Ship Around describe Capt Marquet’s careful and deliberate effort to understand the normal operating patterns of life on the Santa Fe. How did people interact with one another? What mechanisms were inhibiting initiative? What were the sources of fear, hope on board? All in all he found a competent, but dispirited, crew who was not as bad as they allowed themselves to believe they were.

But the process of “making decisions” was paralyzed by mechanisms pulling authority and control to the highest levels of the organization.

He was looking for the mechanisms of the process, of the way work was organized, of the way decisions were made, that were casting the shadow of poor performance and poor morale. He knew he could not address those things directly. He had to deal with the underlying process mechanics, and ultimately learn which ones impacted his key performance metrics.

Establish the Next Target Condition

Capt Marquet was…well… the Captain. His target conditions became challenges for his next levels in the organization. Though he didn’t follow the Improvement Kata precisely, we can see from the actions he took that the mental structure was there.

If we zoom in a level, and look at Capt Marquet’s initial meeting with the Chiefs as outlined in Chapter 8, we actually see the entire pattern.

If you have served in the military, you can bleep over the next section on the role of the Chiefs.

The Role of Non-Commissioned Officers

In the Navy*, “Chiefs” are Chief Petty Officers, senior non-commissioned officers. They are (very) roughly equivalent to supervisors in industry. The saying is that the Officers are responsible for doing the right things, the Chiefs are responsible for doing things right.

In the Navy*, “Chiefs” are Chief Petty Officers, senior non-commissioned officers. They are (very) roughly equivalent to supervisors in industry. The saying is that the Officers are responsible for doing the right things, the Chiefs are responsible for doing things right.

The sailors’ day-to-day interactions are mostly with the Chiefs and more junior Petty Officers, which might be thought of as leads or team leaders.

Thus, it is really the Chiefs that set the tone for the experience of the rest of the crew. If they aren’t “into” the job, aren’t working as a team, it is unlikely the organization below (or above!) them is as effective as it could be, and morale is likely mediocre at best.

The same goes for your supervisors.

Where a military organization differs from industry is that there is a senior non-commissioned-officer paired with an officer at every level of the hierarchy. The most senior noncom on the ship is the “Chief of the Boat” who reports directly to the Captain.

This structure is very beneficial in making sure the Enlisted perspective is brought into every level of decision making.

Although it can, and does, happen, it is relatively rare that an enlisted non-commissioned-officer would become a commissioned officer during his or her career. This is a significant shift in the career path.

Pushing Authority to Create Responsibility

Capt Marquet’s initial experiment to shift the crew dynamics on board the submarine involved the Chief Petty Officers. He meets with them and works with them in an exchange: They get authority. They take responsibility.

A few key points that emerge here are:

- Lecturing people about “taking initiative” and “stepping up” doesn’t work. If it did, our organizations would be operating at phenomenal levels already.

- Capt Marquet talks about the Chiefs as individuals, each with his own strengths, level of commitment, etc.

- There was a clear challenge for them in Capt Marquet’s mind. He knew what he needed from them.

Coaching Through Grasping the Current Condition

Capt Marquet met with the Chiefs, and facilitated a conversation that first sought to arrive at a common understanding of the level of authority the Chiefs really had on the submarine. (almost none, decision making for anything of significance had been pulled up above their level).

Key Point: Capt Marquet likely already knew that the Chiefs had very little authority. But it wouldn’t work to act on that assumption without validating it in the minds of the Chiefs themselves. Further, the Chiefs had to arrive at their own truth, and they had to want to change it.

Based on his assessment, Capt Marquet guided the chiefs through a discussion about their current condition. At this point, they are the learners, the improvers, and he is taking the role of the coach. This is the bullet list he cites in the book:

- Below-average advancement (promotion) rates for their men.

- A lengthy qualification program that yielded few qualified watch standers.

- Poor performance on evaluations for the ship.

- A lean watch bill, with many watch stations port and starboard under way, and three-section in port (the objective was to have three-section at sea and at least four-section in port; this meant that each member would stand watch every third watch rotation— typically six hours on watch and twelve hours off— at sea, and every fourth day in port)

- An inability to schedule, control, and commence work on time.

- An inability to control the schedules of their division and men.

While this is really just a laundry list describing the general working environment that is summarized in the book, my impression is that the group had developed a good common grasp of the processes behind most of these issues. It really came down to the Chief’s authority to decide who needs to do what, and when, had been usurped by various other mechanisms in the chain of command.

If the Chiefs have no real authority to act, then the commissioned officers must make every decision and provide every direction. Those orders are often separated in time and space from the events they are trying to influence. The officers simply can’t be everywhere at once.

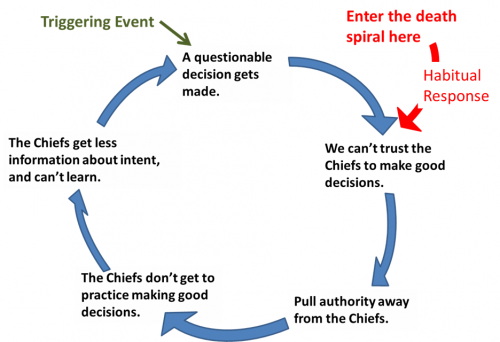

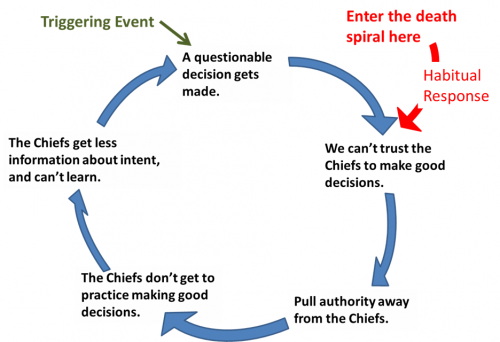

The dynamics can easily trigger a downward, reinforcing spiral of more and more control being pulled higher and higher, which makes the orders even more detached from reality.

And, again, the same is true for your supervisors and team leaders in their relationship with management.

The Chiefs Establish their Target Condition

You can’t direct someone to accept responsibility.

My next question built on what we had all agreed on, namely, the chiefs did not run Santa Fe.

I asked, “Do you want to?”

Reflexively they answered, Yes! Uh-huh. Of course!

“Really?”

And that’s when we began to talk honestly about what the chiefs’ running the submarine would mean.

– David Marquet in Turn the Ship Around

I wanted to make sure they deliberately decided to take charge. It wouldn’t be any good if I directed them.

– David Marquet in Turn the Ship Around

Something that is often lost on managers learning to be coaches is that the coach can’t impose a target condition. Certainly the coach can (and should) structure the challenge in a way that ensures the learner is working on the right things. And the coach must provide guidance to ensure the learner is working on those things the right way.

But it is up to the learner to figure out how to get there, and up to the coach to ensure the learner has the skill and persistence to succeed. It is a mutually dependent relationship.

Many managers are uncomfortable with this because it means giving up control even if they know the right answer (or think they do). It means giving up control especially if they know the right answer! This is actually a lot easier for a coach who doesn’t know exactly what to do!

As the discussion continues in the book, some of the Chiefs begin to realize that with control comes accountability for the results. They won’t be able to hide behind “well, they told me to do it” because “they” is now the face in the mirror.

That is actually harder than just waiting to be told what to do. It is also a lot more rewarding if the work environment is supportive of growth vs. punishing mistakes.

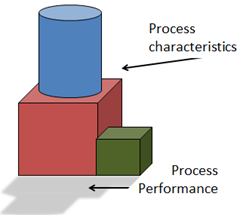

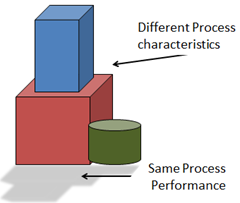

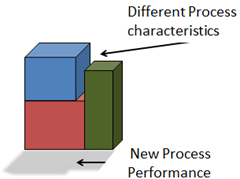

The shape of a target condition

At the end, we were agreed: the sole output would be concrete mechanisms.

While it feels good to describe a future vision with words like “The supervisors will be empowered” that doesn’t address the adjustments and changes that must be made to the mechanisms that are driving the current situation.

If you want your supervisors to have more authority, but aren’t willing to dismantle the mechanisms that are withholding it from them… that isn’t going to work.

I put this question to Santa Fe’s chiefs: “What can we do so that you actually run the ship?”

The target condition they established was to have the Chiefs responsible for authorizing leave (vacation time) for the sailors in their organizations.

(In the military, you can’t just go on vacation whenever you feel like it. They have a mission to accomplish, with or without you there, so there is always a process to ensure too many people aren’t gone at the same time.)

What obstacles are keeping us from reaching the target?

There were a number of things that had to be dealt with to make this work. One of them was that Naval regulations required the Executive Officer (2nd in command) to approve the leaves of Enlisted Men.

This meant that even after the Chief of the Boat reviewed the leave plan, at least three additional officers had to approve as well. This added time and bureaucracy which, in turn, hurt morale because it might be weeks before a sailor knows if he can go home for Christmas, for example.

Related to that was the fact that, because of those additional checks, the Chiefs were inclined to approve leave requests without really thinking about the consequences. They knew someone else would be on the hook to say “no.”

They could be the White Hats, and shift the responsibility elsewhere. This was a consequence of the mechanism. The mechanics are part of the “death spiral” I illustrated above.

Which obstacle are we addressing now?

Here is the dilemma. Capt Marquet could ask the Chiefs to prove they could act responsibility, then give them the authority.

Or he could give them the authority, and trust that to drive responsibility.

In reality, I think only one of those choices actually works: Creating responsibility by pushing authority. The obstacle they addressed was the Navy regulations.

What is your next step or experiment?

The experiment was to actually break Navy regulations. On the Santa Fe, the non-commissioned officers would be solely responsible for approving the leave requests of Enlisted Men.

What result do you expect?

They expected that the Chiefs would start thinking through the consequences of these decisions.

This one-word administrative change put the chiefs squarely in charge of all aspects of managing their men, including their watch bills, qualification schedules, and training school enrollments.

The only way the chiefs could own the leave planning was if they owned the watch bill. The only way they could own the watch bill was if they owned the qualification process.

It turned out that managing leave was only the tip of the iceberg and that it rested on a large supporting base of other work.

– David Marquet in Turn the Ship Around

(I added the line breaks for readability online.)

This, in turn, set off multiple cycles of learning as the crew of the Santa Fe gelled into a true mutually supporting team.

In other parts of the book, Capt Marquet talks about the exchange of intent. These decisions are delegated, but they are not made independently. Rather, they worked to progressively create a working climate where people were saying out loud, both formally and informally, what they intended to do and why.

This created an environment were people could hear, and add to, the collective wisdom being shared around them. Knowledge was out in the open and spread quickly thorough the organization with these mechanisms.

But that was all a future consequence of what they learned by making this single change: To actually break the Navy Regulation, and turn 100% of the leave authority over to the non-commissioned officers.

The Overall Theme

This is just one example. The book is full of learning cycles.

People made mistakes. People acted without understanding the consequences. People acted without thinking.

But each time something happened that was contrary to the vision of the right people making the right decisions with the right information at the right time, instead of engaging in the death spiral, they sought to break it.

The crew (with the Captain as their coach) took the first opportunity to pause, reflect, digest what they had learned, and apply a mechanism into their interaction rules that applied a countermeasure.

Capt Marquet didn’t have a concrete step-by-step plan to get there. He just knew where he wanted to to go, had a clear idea of where he was starting, and took the next logical step.

As each step was taken, the next step was revealed. And so there was a little improvement every day. There was a big improvement on some days. But every day they were paying attention to see what they could learn.

And that is what continuous improvement is all about.

What You Can Do

Read the book. Study the book. Parse the book. Each chapter is a parable with a lesson. Don’t get hung up on the Naval environment, that is just a container for the higher-level story.

Study the lessons that were learned. Ask yourself what analog situations you might have, then go and study them. What mechanisms in your organization are driving people to do the things that they do?

What single change can you make that will have a high leverage impact on the level of authority?

That establishes a target condition.

What would “keep you up at night” (as David Marquet says) if you made that change?

Make that list. Those are your obstacles. Which one are you addressing now?

______

*Just to be clear, I did not serve in the Navy, and my interactions with the Navy were only occasional and brief during my time in the military. I was a commissioned officer in the Army, and the non-commissioned officers are just as important there.

![]()