I’ve been asked to explain the relationship between “Toyota Kata” and Kaizen Events, and I am guessing that the person asking the question isn’t the only one who has the question, so I thought I’d take a crack at it here.

To answer this question, I need to define what I mean when I say “kaizen event.”

Kaizen Events

In a typical western company, a kaizen event is geared toward implementing lean tools. There are exceptions, but I think they are different enough to warrant addressing them separately. (If you don’t read this, I changed my mind as I was writing it.)

At this point, I am going to borrow from an earlier post How Does Kaizen Differ From a Kaizen Event:

The kaizen event leader is usually a specialist whose job is to plan and lead these things, identifies an improvement opportunity. He might be tasked by shop floor management to tackle a chronic or painful problem, or might be executing the “lean plan” that calls for a series of implementation events.

It is his job to plan and execute the event and to bring the expertise of “how to make improvements” to the work force and their leaders.

Here’s the Problem

The full-time kaizen event leaders typically get really good at seeing improvement opportunities, organizing groups for improvement, and quickly getting things done. They get good at it because they do it all of the time.

The area supervisors might be involved in a kaizen event in their area a few times a year if that. Some companies target having each employee in one kaizen event a year.

That’s 40 hours of improvement. All at once. The question is: What do they do (and learn) the other 1900 hours that year?

What do they do when something unexpected happens that disrupts the flow of work? Usually kaizen events don’t deal with how to manage on a day-to-day basis other than leaving an expectation for “standard work” in their wake.

But “standard work” is how you want the work to go when there aren’t any problems. When (not if) there are problems, what’s supposed to happen?

This is why many shop floor leaders think “kaizen” is disconnected from reality. Reality is that parts are late, machines break, things don’t fit, Sally calls in sick, and the assembler has to tap out threads now and then. In the hospital, the meds are late, supply drawers have run out, and there is a safari mounted to find linens.

These things are in the way of running to the standard work. They are obstacles that weren’t discovered (or were glossed over as “resistance to change”) during the workshop.

The supervisor has to get the job done, has to get the stuff out the door, has to make sure the patients’ rooms are turned over, whatever the work is. And nobody is carving out time, or providing technical and organizational support (coaching) to build his skills at using these problems as opportunities for developing his improvement skills, and smoothing out the work.

OK – that is my paradigm for kaizen events. And even if they work really well, the only people who actually get good at breaking down problems, running PDCA cycles, etc. are the professional facilitators or workshop leaders. Many of these practitioners become the “go-to” people for just about everything, and improvement becomes something that management delegates.

What are they good for? Obviously it isn’t all negative, because we keep doing them.

A kaizen event is a good mechanism for bringing together a cross functional team to take on a difficult problem. When “improvement” is regarded as an exception rather than “part of the daily work,” sometimes we have to stake out a week simply to get calendars aligned and make the right people available at the same time.

BUT… consider if you would an organization that put in a formal daily structure to address these things, and talked about what was (or was not) getting done on a daily basis with the boss.

No, it wasn’t “Toyota Kata” like it is described in the book, but if that book had been available at the time, it would have been. But they had a mechanism that drove learning, and shifted their conversations into the language of learning and problem solving, and that is the objective of ALL of this.

Instead of forcing themselves to carve out a week or two a year, they instead focused on making improvement and problem-solving a daily habit. And because it is a daily habit, it is now (as of my last contact with them a couple of months ago), deeply embedded into “the way we do things” and I doubt they’re that conscious of it anymore.

This organization still ran “event” like activities, especially in new product introduction.

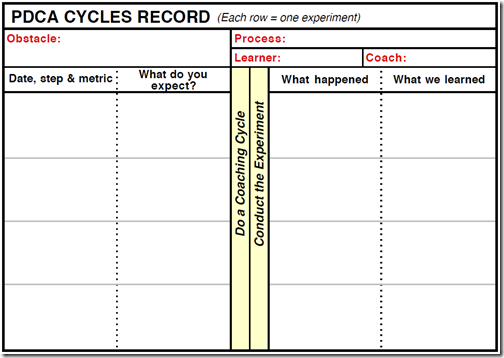

In another company, a dedicated team ran the layout and machinery concepts of a new product line through countless PDCA cycles by using mockups. These type of events have been kind of branded “3P” but because changes and experiments can be run very rapidly, the improvement kata just naturally flows with it.

Kaizen Events as Toyota Kata Kickstarts

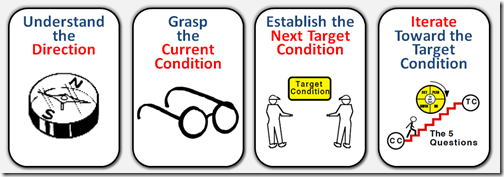

If you take a deeper look into the structure of a kaizen event, they generally follow the improvement kata. The team gets a goal (the challenge), they spend a day or so grasping the current condition – process mapping, taking cycle times, etc; they develop some kind of target end state, often called a vision, sometimes called the target and mapped on a “target sheet.” Then they start applying “ideas” to get to the goal.

At the end of the week, they report-out on what they have accomplished, and what they have left to do.

If we were to take that fundamental structure, and be more rigorous about application of Toyota Kata, and engage the area’s leader as the “learner” who is ensuring all of the “ideas” are structured as experiments, and applied the coaching kata on top of it all… we would have a pretty decent way to kickstart Toyota Kata into an area of the organization.

Now, on Monday morning, it isn’t what is left to do. It is the next target condition or the next obstacle or the next PDCA cycle.

Toyota Kata

If we are applying Toyota Kata the correct way, we are building the improvement skills of line leadership, and hopefully they are making a shift and taking on improvement is a core part of their daily job, versus something they ensure others are doing.

One thing to keep in mind: The improvement kata is a practice routine for developing a pattern of thinking. It is not intended to be a new “improvement technique,” because it uses the same improvement techniques we have been using for decades.

The coaching kata is a practice routine to learn how to verify the line-of-reasoning of someone working on improvements, and keep them on a thinking pattern that works.

By practicing these things on a daily basis, these thought patterns can become habits and the idea of needing a special event with a professional facilitator becomes redundant. We need the special event and professional facilitator today because a lot of very competent people don’t know how to do it. When everybody does it habitually, you end up hearing regular meetings being conducted with this language.

We can be more clear about what skills we are trying to develop, and more easily assess whether we are following sound thinking to arrive at a solution. (Luck is another way that can look the same unless the line of reasoning is explained.)

What About A3?

When used as originally intended, the A3 is also a mechanism for coaching someone through the improvement pattern. There are likely variations from the formal improvement kata the way that Mike Rother defines it.

However, if you check out John Shook’s book Managing to Learn, you will see the coaching process as primary in how the A3 is used. Managing to Learn doesn’t describe a practice routine for beginners. Rather, it showcases a mature organization practicing what they use the Improvement Kata and the Coaching Kata to learn how to do.

The A3 itself is just a portable version of an improvement board. It facilitates a sit-down conversation across a table for a problem that is perhaps slightly more complex.

An added afterthought – the A3 is a sophisticated tool. It is powerful, flexible, but requires a skilled coach to bring out the best from it. It can function as a solo thing, but that misses the entire point.

For a coach that is just learning, who is coaching an improver who is just learning, all of the flexibility means the coach must spend extra time creating structure and imposing it. I’ve seen attempts at that – creating standard A3 “templates” and handing them out as if filling out the blocks will cause the process to execute.

The improvement kata is a routine for beginners to practice.

The coaching kata is a routine for beginners to practice.

Although you might want to end up flying one of these (notice this aircraft is a flight trainer by the way):

They usually start you off in something like this:

The high-performance aircraft requires a much higher level of instructor skill to teach an experienced pilot to fly it.

And finally, though others may differ, I have not seen much good come from throwing them up on a big screen and using them as a briefing format. That is still “seeking approval” behavior vs. “being coaching on the thinking process.” As I said, your mileage may vary here. It really depends on the intent of the boss – is he there to develop people, or there to grant approval or pick apart proposals?

So How Do They All Relate?

The improvement kata is (or absolutely should be) the underlying structure of any improvement activity, be it daily improvement, a staff meeting discussing changes in policy, a conversation about desired outcomes for customers (or patients!).

The open “think out loud” conversation flushes out the thinking behind the proposal, the action item, the adjustment to the process. It slows people down a bit so they aren’t jumping to a solution before being able to articulate the problem.

Using the improvement kata on a daily basis, across the gamut of conversations about problems, changes, adjustments and improvements strengthens the analytical thinking skills of a much wider swath of the organization than participating in one or two kaizen events a year. There is also no possible way to successfully just “attend” an improvement activity if you are the learner being coached.

![]()