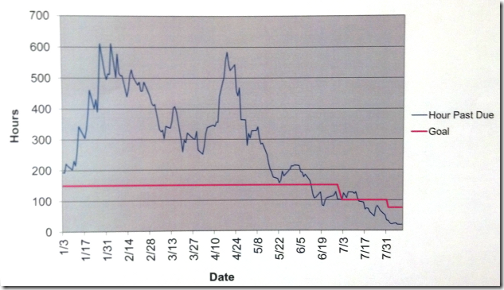

Past Due Hours

This area was picked for the initial focus because they were way, way behind, and it was getting worse.

The initial work was done in mid-April. The target was consistent output at takt time.

As the team looked at the process, and identified the sources of disruption and variation, “changeovers” surfaced pretty quickly as a main issue.

“Which obstacle are you addressing now?” was the changeover times on the output process, so the target condition for the area’s team was to get the disruption to output for a change over down to a single takt time vs. the highly variable (up to 10 takt times or more) disruptions they were seeing.

One big mindset change was the concept of takt time. There was a lot of perceived variation in the run times of these parts. But upon study, the team realized the variation was a lot less than they thought. Yes, it is there, but over any given couple of hours, it all evens out most of the time.

As the team studied their changeovers, one of them had an insight that “We can do a lot of these things before we shut the machine down.” And in that moment, the team invented the SMED methodology of dividing “internal” and “external” changeover tasks.

Once that objective was grasped, they went to town, and saw lots of opportunities for getting most of the setup done while the last part was still running.

Their lot sizes were already quite small, the core issue here was the disruption of output caused by the increased tempo of changeovers. So that time was put back into capacity, resulting in the results you see above.

They continue to work on their changeover times, have steadily reduced the WIP between process stages, and (as you can see) keep outrunning their goals for “past due hours.”

But the really important bit here is that this was largely the team leaders, the supervisor, and the area manager. Yes, there was technical advice and some direction giving by the VP and the Continuous Improvement manager, but the heavy lifting was done by the people who do the work every day.

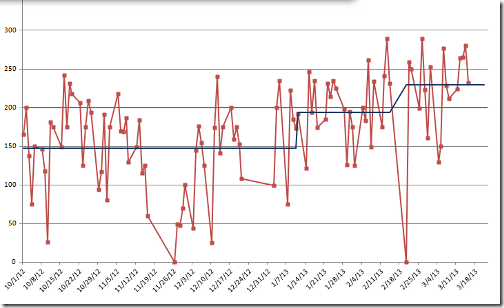

Consistent Output

This is from another company, in a completely different industry. Their issue, too, was that they were always behind. In this industry, the idea of a takt time is pretty alien. Even the idea of striving for a fixed level of output every day is pretty alien.

The team’s initial focus was maintenance time. They perceived that equipment reliability was causing them to fall behind in production, and so were shipping product to a sister plant every week to fill in the gaps.

The first question posed to them was “How much time is needed for production?”

In other words, they needed to figure out how much production time was “enough,” so they could then assess how much time maintenance could have. That would establish their target.

But in answering that question, they developed a takt time, then measured output cycles vs. that takt. What they saw was lots of inconsistency in the way the work was being done.

If they could hold to something close to their demonstrated lowest-repeatable cycle times, they could then know when they were “done” for a given shift, or day, and actually plan on maintenance time rather than seeing it as a disruption to production.

The focus shifted to the work cycles.

What is cool about this team is that the team leader / “learner” (in Toyota Kata terms) was the maintenance manager.

He gained a real shift in perspective. “Production” were no longer the people who wouldn’t let him maintain the machine, they were his customers, to whom maintenance needs to deliver a specified, targeted, level of availability as first priority.

The teamwork developed about the end of Day 2 of this intense learning week, and they have been going after “sources of variation” ever since.

Here is the result in terms of “daily output:”

As you can see, not only is the moving average increasing, but the range is tightening up as they continue to work on sources of variation.

The big downward spike on the right is two days of unplanned downtime. In retrospect, they learned two things from that.

- After foundering a bit, they applied the same PDCA discipline to their troubleshooting, and got to the issue pretty quickly. As a sub-bullet here, “What changed?” was a core question, and it turned out someone had known “what had changed” but hadn’t been consulted early on. Lesson learned – go to the actual place, talk to EVERYONE who is involved rather than relying on assumptions.

- Though they sent product out for processing, they realized they could have waited out the problem and caught up very quickly (with no customer impact) had they had more faith in their new process.

All pretty cool stuff.

These things are why this work is fun.