5S audits, standard work audits, and for that matter ISO-900x audits, are a frequent source of questions in various online discussion forums. At the same time, the topic of “leader standard work” comes up frequently, as it did in a recent question / comment on “Walking the Gemba.”

I think the topic is worth exploring a bit.

Let’s start with audits.

Typically the purpose of an audit is to check compliance with a standard. The auditor has a checklist of some kind that defines various levels of compliance. He evaluates the current situation against the checklist, and produces a score, a report of discrepancies, a pass/fail evaluation of some kind.

So, for example, a typical 5S audit would assign various criteria in each of the 5 ‘S’ words, and assign a 1-5 scale against each of them. Periodically, the person responsible for 5S will come into the work area, do an audit, and post the score. Often there is a campaign to “get to level 3” or something.

Although there are fewer boilerplate checklists out there, “standard work audits” tend to be pretty similar, at least the ones I have seen.

Further up the scale is something like an ISO 900x audit, or an “Class-A MRP II” audit or a corporate “lean assessment.” These are often done by outside agencies to certify the organization. There is a lot of work up front to pass the audit, a plaque goes on the wall, and everybody is happy.

So what’s the problem? (this is turning into one of my favorite questions)

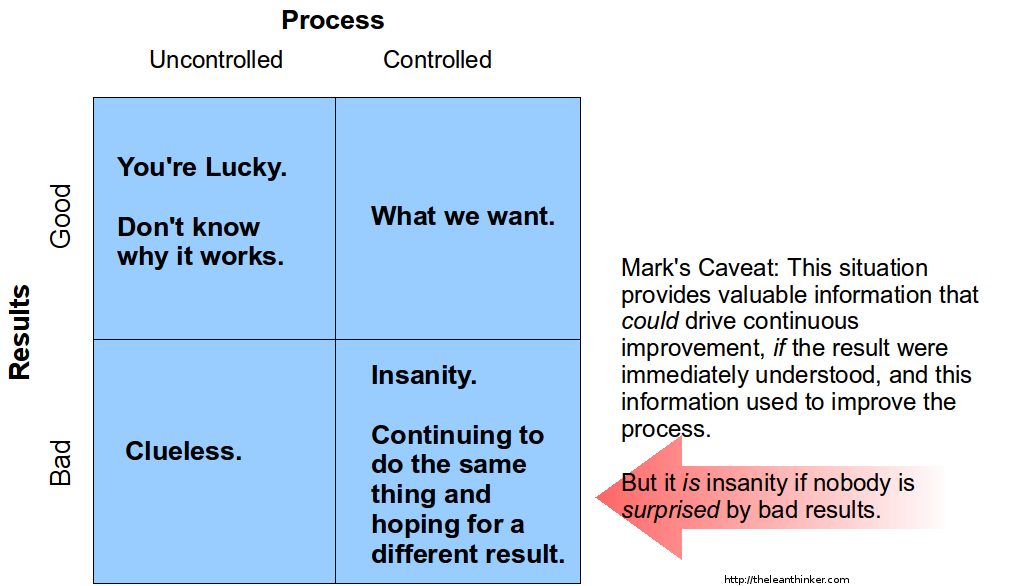

The key is in the difference between a “check” and a “countermeasure.”

A countermeasure is a change or adjustment to the system itself so that the root cause of a problem, or at least its effect, is eliminated.

Audits, on the other hand, actually change nothing about the underlying system. All they do is assess the current state against some (presumed) standard.

Yet so many organizations try to use “audits” as a means to alter the system.

What an audit is good for (if it is planned and performed well – a big assumption) is to CHECK to see if the other things you are doing are working. But, by itself, it is “management by measurement.” People will do what they must to pass an audit (if it even matters that much to them), then go back to what they were doing before.

Leader Standard Work operates at a much lower level of granularity, and looks for different things. Think of the analogy in a previous post about cost accounting:

When dieting, standard cost accounting would advise you to weigh yourself once a week to see if you’re losing weight. Lean accounting would measure your calorie intake and your exercise and then attempt to adjust them until you achieve the desired outcome.

So, to paraphrase, audits are weighing yourself once a week (or once a quarter!) to see if you are losing weight. Leader standard work, on the other hand, is a process to continuously verify that the calorie intake is as specified, and the exercise is as specified, while those things are being done.

That, in turn, implies that there is a daily plan for calorie intake, and a daily plan for exercise. Without those specifications, there is nothing to check.

Leader standard work defines what the leader will check, when it will be checked, and how it will be checked. It also defines how the leader will respond if there is a problem.

He is looking for solid evidence of control.

Are things going as planned?

Is anything disrupting the work cycles or flow of material?

Are quality checks being made as specified?

And, in my opinion, the most important: Are problems being handled correctly, or worked around?

This is important because a culture of working around problems is one in which problems are routinely hidden, often without malice and with the best of intentions. But hidden problems remain, come up again tomorrow, and become part of the routine, adding a little waste, a little friction, making the system a little worse every day.

The typical effort to “pass an audit” reinforces this – it actually hides problems, and the auditor’s job is to ferret them out. This is the exact opposite of the kind of problem transparency we need.

It is human nature to work around problems, and it is the default behavior, everywhere. It takes constant leader vigilance, coaching, response to prevent it.