Corrie van den Hoek, a regular reader and correspondent from The Netherlands, is working on applying kaizen in the health care industry. She left a comment on ‘The White Board’ asking my thoughts on the concepts of mura and muri in the health care field.

I think it is first important to define the terms because (1) Not everyone has heard them and (2) The translations from Japanese can differ a bit.

Mura is usually translated as “inconsistency.”

Muri is usually translated as “overburden.”

Mura and Muri are the brothers of the better-known Muda, which, of course, translates as “waste” or “unnecessary work.”

I am aware that it is possible to split hairs on the translations, but I think these suffice for the sake of discussion.

Like any industry, Health Care has a product to deliver (treatment of patients) and the administrative processes that support the care givers, patients, and keep it running as a business. There is huge room for improvement in both of these areas, and of course problems in one have impact on the other.

I started to get to these issues in this post, but did not go into any depth. The cool thing is that the article I was writing about in a general sense is actually written from a health care context. So I highly recommend reading it as some additional background.

Muri – Overburden – “Asking the unreasonable or impossible.”

In the article, Tucker and Edmondson refer to an “error” as doing something inappropriate or unnecessary, and a “problem” as something which interferes with accomplishing a task in the specified way.

Problems as Overburden

They cite a typical example of a problem. A Team Member’s task is to change linens. This task is routine. She goes to the storage area for linens on her floor, and finds none. She goes to another floor, and perhaps another, and ultimately finds the linens she needs, then returns to the task she was trying to accomplish in the first place. (She at least did not have to hire a taxi to deliver fresh linens from the service, as other caregivers reported they had done.)

At the end of the shift, however, I would wager this Team Member wasn’t able to get everything done. Or she had to hurry to do things. Perhaps the work left undone is now passed to someone else and will disrupt their work. All of this is an example of overburden – asking (or implicitly expecting) Team Members to do more than they should, or more than they can. At the very least, the floor she took the linens from now has fewer than they probably need, and another safari will be launched from that floor tomorrow.

In this case, the Team Member is implicitly expected to “do what must be done” in order to deliver care. There are no avenues to address, or even call out, the existence of these problems. Calling them out carries at least an implied professional or psychological risk of being branded a complainer, or “not a team player.”

Indeed, working around these kinds of issues is a major source of satisfaction and pride in the work culture. I quote from a quote in the article:

Working around problems is just part of my job. By being able to get IV bags or whatever else I need, it enables me to do my job and to have a positive impact on a person’s life – like being able to get them clean linen. And I am the kind of person who does not just get one set of linen, I will bring back several for the other nurses.

For management, the question is a simple one: Is this task one which you would deliberately design into this person’s work process? If not, then question why it must be done at all. But you can’t just question it. That implies the person doing it is doing something wrong. She isn’t. She is doing exactly what must be done to do the job she was given. Question why it must be done so you can remove the necessity to do it.

The Muri of Unnecessary Life-and-Death Decisions

Overburden is also the case where a Team Member is asked to make multiple perfect decisions in high-stress situations. I am not talking about deliberate decisions about, for example, what type of care to deliver. Rather I am talking about the simple decisions that are repeatedly forced on Team Members during the routine delivery of care. Many of these seemingly simple decisions are overburden because the Team Member should not be asked to make them at all. Making them adds to the work stress because, in medical care delivery, the consequences of an error can be catastrophic in terms of “negative patient outcome.”

A case that comes up time and time again in examples I hear – both from literature and in my own conversation with people inside the system is a classic one: A Team Member selects the wrong small vial of colorless liquid from a shelf or tray and injects it into a patient. Sometimes this is harmless. Other times it is fatal. These mistakes, however, only get the attention of the system when there is harm to the patient. And the attention of the system is nearly always focused on finding out who did it and assigning blame.

Steven Spear recounts a typical case in Fixing Health Care From The Inside .

.

He cites an investigation into a case where a woman recovering from routine surgery suddenly developed seizures. Her blood sugar level crashed, she lapsed into coma and died. Here is a key point from the investigation:

a nurse had responded to an alarm indicating that an arterial line had been blocked by a blood clot, and he had meant to flush the line with an anticoagulant, heparin. There was, however, no evidence that any heparin had been administered. What investigators did find was a used vial of insulin on the medication cart outside Mrs. Grant’s room, even though she had no condition for which insulin would be needed.

Instead of asking “Why did the care giver administer insulin instead of heparin?” how about asking “Why was insulin even in the room in the first place? This is simple 5S – eliminating the things that are not needed. Actually no. This is somewhat advanced 5S, because it is eliminating the things that are not needed NOW. Perhaps it is appropriate to have insulin in the room for some patients. But it apparently was not appropriate for this patient. And even if there are non-routine conditions which could require insulin, then the insulin should be stored in a place that forces a conscious and deliberate decision to retrieve it.

Key Point: Separate the routine from the non-routine. Separate normal from abnormal.

Another example was cited directly to me by a friend who works in Health Care. In another big-name big-city hospital a woman was in routine surgery. A staffer in the operating room chose between two clear vials of clear liquid, picked up the wrong one, and administered a cleaning substance to the patient, killing her.

Of course this scenario begs exactly the same questions as the one above it. If it doesn’t go into the patient, why is it in the room at the same time the patient is? And if must be in the room, why is it accessible in a routine way to a routine process?

Spear points out that for every death or serious injury there are many instances of these errors that do not result in serious problems, and many times that number of instances where the error is almost made, but it caught and corrected in time.

This is, in my opinion, a form of “overburden” because people are being asked to make decisions that have life-and-death consequences, and those decisions are entirely unnecessary if someone would only ask “Why did this person have to choose?” instead of “Who made the wrong choice” or (a little bit better) “Why was the wrong choice made?”

Whenever we inject ambiguity into the situation (or even allow ambiguity to persist) we are expecting someone – who may not expect it – to see it and resolve it.

Countermeasures:

Most times the proposed solution is around better labeling and identification. But I would like to suggest that “mistake proofing” is actually a process of:

- Systemically eliminating sources of errors by eliminating choices;

- If that can’t be done then putting up barriers that stop the process if an error is about to occur;

- and if that can’t be done by doing something that breaks unconscious routine in a way that forces the person to notice the impending error.

Better labeling falls into the third category here. Ask tougher questions, and support your people better.

What about Mura, or inconsistency?

Traditionally this is about a widely varying workload. In industry, the countermeasures are to establish a takt time, apply production leveling, set cycle times to the takt, and in general, work hard to keep the workload as even as possible. There are a lot of good benefits to this and the performance of the companies that do it very well suggests that doing it is worth the perceived costs and trouble.

One of the things frequently cited by Health Care is how their workload is wildly variant and unpredictable. These perceptions are certainly not unique to Health Care, but it is probably worthwhile exploring the situation from their context. I certainly don’t expect the Health Care community to make the leap from consumer goods or dump trucks to patient workloads and processing insurance claims.

Based on my limited dealing with Health Care, I am going to do a little conjecture, then attempt to go from there. If I am totally off base with my assumptions, feel free to correct me in a comment, and I’ll re-think.

As I see it, two big drivers for high day-to-day variation of demand on the system are:

- Patients can show up at any time. This is especially true in Emergency Services, where, by definition, demand is unprogrammed.

- Each individual case is potentially unique, or at the least, any one of them could go from routine to non-routine at any time.

Does that about capture it?

Shifting The Thinking A Bit

Not everything I propose here will work every time – there are true exceptions out there. But, in general, at least one of these concepts have usually helped people find some foundation of stability they can leverage.

Rather than looking at a varying aggregate workload, start breaking things down into individual streams, and finding components of stability within the variation.

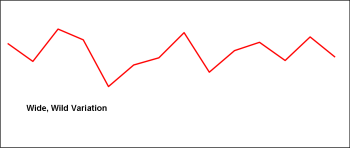

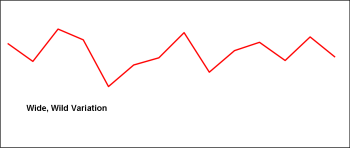

This graph represents a wildly varying workload. Most reasonable people are going to look at this and conclude they pretty much have to either be ready for anything, in any form, at any time.

But even in the face of wide demand swings, it is a rare operation the experiences -zero- or close to zero demand. There is some element which is reliable. Perhaps that element is small, but, at some level, it is usually there.

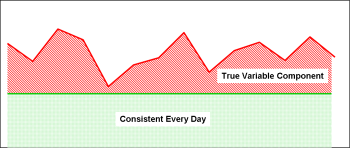

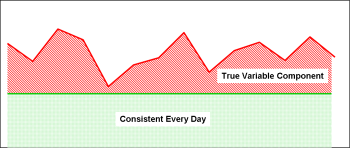

At first you probably won’t be able to control the wide swings, but what you can do is apply the principle of isolating instability.

This is exactly the same graph as the first one. The difference is the shading. The consistent part of the workload is shaded in green, the unstable or varying workload is shaded in red.

If you look for sources of stability, vs. causes or sources of instability, most operations can usually find something to leverage. This works particularly well in administrative processes, but I’ll work on applying it to the care-delivery flow in a bit.

An Administrative Flow

(Thanks to the GHC team for making me think about this in their context)

Imagine, if you will, a routine administrative process that is carried out many times a day. Many, if not most, of these processes involve something along the lines of:

- Getting some initial piece of information that triggers the process itself.

- Confirming known information, frequently doing routine research to gather more information.

- Summarizing that information in some formal manner – a report, a request, a transaction.

In my little example a process just like this one was experiencing wildly varying workloads from day to day. Some days they could process 15 or more, other days they would get bogged down with one. Some days they would receive a lot, other days they would receive a few. The Arrivals followed all of the queuing models – work arrived in batches, in distribution biased to the right, with a long left tail. The team was working Saturdays and long hours just to keep up, and was often getting further and further behind.

To level the workload we had to do two things. First, we needed to understand the actual demand over some reasonable period of time. We took a week since that time interval matched the kinds of deadlines they were usually under. Your mileage may vary. Based on that, we looked at how many per day they needed to get through, every day, to keep up with the demand they were experiencing. From that we established a nominal takt time of an hour.

For the cases that arrived reasonably complete, and were reasonably routine, one person could easily complete the work in an hour. The first countermeasure, therefore, was to put an upstream filter into place. The idea was that one person would be dedicated to routine transactions. The supervisor would do a quick review for completeness, and if the “routine” criteria were met, they would be placed in the appropriate work queue.

This process had a built-in check. The assumption being tested was that a complete case should take an hour to process, never longer. If a case took longer than an hour to process, it should not have been placed in the “routine work queue.” Thus, at the 60 minute mark, if the processor was not done, he kicked that one out of the work queue, back to the supervisor and started the next one.

This process immediately stabilized and accelerated the throughput on the vast majority of cases which were, in fact, routine. Everything went faster because they were no longer stopping the entire train to deal with an exception. The routine stuff went through routinely. They isolated variable processing from routine processing.

Of course they didn’t ignore the abnormal cases. There were two types of exceptions to handle.

- The case that should have been routine, but was not because it was lacking something required to process it.

- The case was truly an exception – something difficult or complicated, which even with complete information, requires more work than normal to be processed.

In the first few weeks, the team had a lot of cases get kicked out of the “routine” work queue. Then the numbers started to drop. This is because, each time, the team learned a little more about what causes line stops, and did a little better job:

- Defining what they needed from their upstream processes, and making sure they got it.

- Screening the incoming work to make sure it was set to process routinely and quickly.

What about the true exceptions? These, of course, remained. But they no longer clogged up the pipeline and stopped processing of the routine. The true exceptions were managed from a priority queue with a visual control. The other team members would pick the next one on the queue, and work it. The group’s supervisor could re-shuffle the work queue at any point, so the most important was always the next one to be picked. However, as a rule, he would not interrupt a Team Member from one case to work another.

Over a fairly short period of time, the group’s throughput went up dramatically, they were no longer working weekends and overtime, and there was far less rework involved because they were catching the reasons for rework up front.

Now, apply this same thinking to any transaction that occurs in your Health Care arena. Processing insurance claims (or other financial transaction), for example, seems like something fairly similar to this.

But here is the point: Isolate the routine from the true exceptions. Establish a routine process to do routine things in routine ways. Process the exceptions separately.

What about delivery of care?

This gets a little trickier, but I think the same basic processes apply. If you think about it, most Emergency Rooms already do this with triage. But where they fall short is in establishing routines to do routine things, and having checks in place to make sure those things are happening as specified.

Thus, even with the best of intentions, the exceptions become the norm because they are allowed to become the norm.

Let’s look at routine, scheduled, surgery. There are fixed sequences of steps to prepare the patient, prepare the facility, and prepare the team. But I would contend that, even though “everybody knows what to do” there isn’t an expectation that everybody does it a particular way. The “Who does What, When” is not part of the expected routine. Thus, people don’t expect routine things to actually BE routine, so the non-routine things that mess up the process are taken as a matter of course.

Instead, assume that a routine, smooth, consistent process is possible. Then look for what keeps it from being ideal, and embrace those little things as kaizen opportunities… then address them!

This post is MUCH longer than I set out to make it. But I think the original question gets to the very core of the work most Health Care organizations need to tackle. I am going to stop writing, and throw it out there. I apologize if it is a little unpolished.

Hopefully it will generate a little discussion.