As I promised, I want to expand on a couple of great points buried in John Shook’s new book Managing to Learn, published by LEI.

A while back I commented on an article, Lean Dilemma: System Principles vs. Management Accounting Controls, in which H. Thomas Johnson points out that

Perhaps what you measure is what you get.

More likely, what you measure is all you get. What you don’t (or can’t) measure is lost.

In his introduction to the book, Shook describes the contrast:

Where the laissez-faire, hands-off manager will content himself to set targets and delegate everything, essentially saying, “I don’t care how you do it, as long as you get the results,” the Toyota manager desperately wants to know how you’ll do it, saying “I want to hear everything about your thinking, tell me about your plans.”

and a little later:

This is a stark contrast to the results-only oriented management-by-numbers approach.

Shook then also references H. Thomas Johnson’s paper. (like minds?)

But I would like to dive a little deeper into the contrast of leadership cultures here.

Let’s say the “management by measurement” leader thinks there is too much working capital tied up in excess inventory.

His countermeasure would be to set a key performance indicator (KPI) of inventory levels, or inventory turns, and “hold people accountable” for hitting their targets.

Since there is little interest expressed in how this is done, the savvy numbers-focused subordinate understands the accounting system and sees that inventory levels are taken at the end of each financial quarter, and those levels are used to generate the report of inventory turns. This is also the number used to report to the shareholders and the SEC.

His response is to take actions necessary to get inventory as low as possible during the week or on the day when that snapshot is taken. It is then a simple matter to take actions necessary. A couple of classics are:

- Pull forward orders from next quarter, fill and ship them early.

- Slow down (or even stop) production in the last week or two of the quarter.

- Shift inventory from “finished goods” to “in transit” to get it off the books.

While, in my opinion (which is all that is), actions like this are at best deceptive, and (when reported as true financial results) possibly bordering on fraud, the truth is that these kinds of things happen all of the time in reputable companies.

So what is the countermeasure?

In a “management by measurement” culture, the leader (if he cares in the first place), would respond to put in additional measurements and rules that, hopefully, constrain the behavior he does not want. He would start measuring inventory levels more often, or take an average. He would measure scheduled vs. actual ship dates. He would measure “linearity” of production.

Fundamentally, he would operate on the belief that, if only he could measure the right things, that he would get the performance he needs, in the way it should be done. “The right measurements produce the right results.”

While not universal, it is also very common for a work environment such as this one to:

- Attach substantial performance bonuses to “hitting the numbers.”

- Confuse this with “empowerment” – and perceive a subordinate who truly wants help to develop a good, sound plan as less capable than one who “just gets it done.” He is seen as “high maintenance.” (“Don’t come to me with problems unless you have a solution.”)

- Look for external factors that excuse not hitting the targets. (Such as an increase in commodity prices.)

- Take credit for hitting the targets, even when it was caused by external factors. (Such as a drop in commodity prices.)

Overall, there is no real interest in the assessment of why there even is a gap between the current value and the target (why do we need this inventory in the first place?); and there is even less interest in a plan to close the gap, or in understanding if success (or failure) was due to successful execution or just plain luck.

The higher-level leader says he “trusts his people” and as such, is disengaged, uninformed, and worse, is taking no action to develop their capabilities. He has no way to distinguish between the people who “hit the numbers” due to luck and circumstances (or are very skilled at finding external factors to blame) and the ones who apply good thinking, and carry out good plans. Because the negative effects often take time to manifest, this process can actually bias toward someone who can get good short-term results, even at the cost of long-term shareholder value.

This is no way to run a business. A lot of businesses, some of them very reputable, are run exactly this way.

So What’s The Alternative?

Shook describes a patient-yet-relentless leader who is determined to get the results he wants by developing his subordinate. He assigns a challenging task, specifies the approach (the “A3 Problem Solving Process”) then iterates through the learning process – while applying the principle of small steps. At no point does he allow the next step to proceed until the current one is done correctly.

“Do not accept, create, or pass on poor quality.”

He has a standard, and teaches to that standard.

He is skeptical and intently curious – he must be convinced that the current situation is understood.

He must be convinced that the root cause is understood.

He must be convinced that all alternative countermeasures were explored.

He must be convinced that everyone involved has been consulted.

He must be convinced that all necessary countermeasures are deployed – even ones that are unpopular.

He must be convinced that the plan is being tracked during execution, results are checked against expectations, and additional countermeasures are applied to handle any gaps.

And he must be convinced that the results came as an outcome of specific actions taken, not just luck.

In short, even though he might have been able to do it quicker by just telling his subordinate what to do, in the end, that Team Member would only know his boss’s opinion on a particular solution for a specific issue… he would not have taught how to be thorough.

The Learning Countermeasure

If we start in the same place – too much inventory, too few turns – the engaged leader starts the same way, by setting a target.

Then he asks each of his subordinates to come back to him with their plan.

By definition that plan includes details of their understanding of the situation – where the inventory is, why it is. It includes targets – where the effort will be focused, and what results are expected.

The plan includes detailed understanding of the problems (causes) which must be addressed so that the system can operate in a sustainable, stable way, at the reduced inventory levels.

It includes the actions which will be taken – who will do what by when, and the results expected from those actions. It may include other actions considered, but not taken, and why.

It includes a process to track actions, verify results, and apply additional countermeasures when there is a barrier to execution or a gap in the outcome.

The process of making the plan would largely follow the outline in Managing to Learn. The engaged leader is going to challenge the thinking at each step of the process. He is going to push until he is convinced that the Team Member has thoroughly understood – and verified – the current situation, and that the actions will close the gap to the targets.

Rather than assigning a blanket reduction target, the engaged leader might start there, but would allow the Team Members to play off each other in a form of “cap and trade.” The leader’s target needs to get hit, but different sectors may have different challenges. Blanket goals rarely are appropriate as anything but a starting point. But it is only after everyone understands their situation, and works as a team, that they could come up with a system solution that would work.

Of course then the Team Members who had to take on less ambitious targets would get that much more attention and challenge – thus pushing the team to ever higher performance.

Today’s World

Even in companies deploying “lean”, the quality of the deployment is dependent on the person in charge of that piece of the operation. When someone else rotates in, the new leader imposes his vision of how things should be done, and everything changes.

There are, in my view, two nearly universal points of failure here.

- The company leadership had an expectation to “get lean” but, above that local level, really had no idea what it means… except in terms of performance metrics. This is often wrapped in a facade of “management support.” Thus, there is no expectation that an incoming leader do things in any particular way. (What is your process to “on board” a new leader prior to just turning him loose with your profits and losses?)

- The outgoing leader may have done the right things in the wrong way – by directing what was to be done vs. guiding people through the process of true understanding.

Fixing this requires the same thinking and the same process as addressing any other problem. Just trying to impose a standard on things like production boards isn’t going to work. The issue is in the thinking, not in the tools.

Conclusion

You get what you measure, but don’t be surprised if people are ingenious in destructive ways in how they get there.

You can’t force a solution by adding even more metrics.

Only by knowing what you did (the process) will you know why you got the results you achieved (or did not achieve). This is a process of prediction, and is the only way people learn.

Learning takes practice. Practice requires humility and a mentor or teacher who can see and correct.

In the world of science, great discoveries simplify our understanding. When Copernicus hypothesized that everything in the universe does not

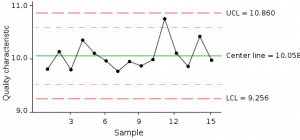

In the world of science, great discoveries simplify our understanding. When Copernicus hypothesized that everything in the universe does not  At its most basic level, the process of statistical process control does exactly that. The chart continuously asks and answers the question “Is this sample what we would expect from this process?” If the answer to that question is “No” then the “special cause” must be investigated and understood.

At its most basic level, the process of statistical process control does exactly that. The chart continuously asks and answers the question “Is this sample what we would expect from this process?” If the answer to that question is “No” then the “special cause” must be investigated and understood.