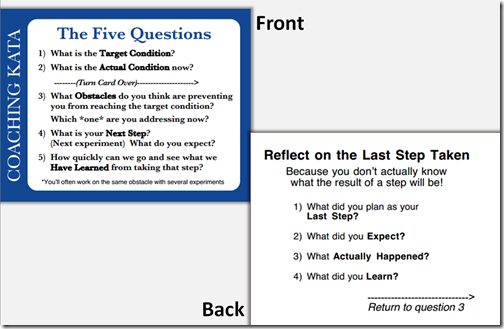

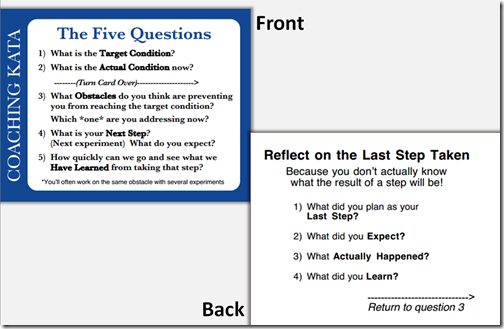

The “Five Questions” are a very effective way to structure a coaching / learning conversation when all parties are more or less comfortable with the process.

Some learners, however, seriously struggle with both the thinking pattern and the process of improvement itself. They can get so focused on answering the 5 questions “correctly” that they lose sight of the objective – to learn.

A coach, in turn, can exacerbate this by focusing too much on the kata and too little on the question: “Is the learner learning?”

I have been on a fairly steep learning curve* in my own journey to discover how modify my style in a way that is effective. I would like to share some of my experience with you.

I think there are a few different factors that could be in play for a learner that is struggling. For sure, they can overlap, but still it has helped me recently to become more mindful and step back and understand what factors I am dealing with vs. just boring in.

None of this has anything to do with the learner as a person. Everyone brings the developed the habits and responses they have developed throughout their life which were necessary for them to survive in their work environment and their lives up to this point.

Sometimes the improvement kata runs totally against the grain of some of these previous experiences. In these cases, the learner is going to struggle because, bluntly, her or his brain is sounding very LOUD warning signals of danger from a very low level. It just feels wrong, and they probably can’t articulate.

Sometimes the idea of a testable outcome runs against a “I can’t reveal what I don’t know” mindset. In the US at least, we start teaching that mindset in elementary school.

What is the Point of Coaching?

“Start with why” is advice for me, you, the coach.

“What is the purpose of this conversation?” Losing track of the purpose is the first step into the abyss of a failed coaching cycle.

Overall Direction

The learner is here to learn two things:

- The mindset of improvement and systematic problem solving.

- Gain a detailed, thorough understanding of the dynamics of the process being addressed.

I want to dive into this a bit, because “ensure the learner precisely follows the Improvement Kata” is not the purpose.

Let me say that again: The learner is not here to “learn the Improvement Kata.”

The learner is here to learn the mindset and thinking pattern that drives solid problem solving, and by applying that mindset, develop deep learning about the process being addressed.

There are some side-benefits as the learner develops good systems thinking.

Learning and following the Improvement Kata is ONE structured approach for learning this mindset.

The Coaching Kata, especially the “Five Questions” is ONE approach for teaching this mindset.

The Current Condition

Obviously there isn’t a single current condition that applies to all learners. But maybe that insight only follows being clear about the objective.

What we can’t do is assume:

- Any given learner will pick this up at the same pace.

- Any given learner will be comfortable with digging into their process.

- Any given learner will be comfortable sharing what they have discovered, especially if it is “less than ideal.”

In addition:

- Many learners are totally unused to writing down precisely what they are thinking. They may, indeed, have a lot of problems doing this.

- Many learners are not used to describing things in detail.

- Many learners are not used to thinking in terms of logical cause-effect.

- The idea of actually predicting the result in a tangible / measurable way can be very scary, especially if there is a history of being “made wrong” for being wrong.

Key Point: It doesn’t matter whether you (or me), the coach, has the most noble of intentions. If the learner is uncomfortable with the idea of “being wrong” this is going to be a lot harder.

Summary: The Improvement Kata is a proven, effective mechanism for helping a learner gain these understandings, but it isn’t the only way.

The Coaching Kata is a proven, effective mechanism for helping a coach learn the skills to guide a learner through learning these things.

For the Improvement Kata / Coaching Kata to work effectively, the learner must also learn how to apply the precise structure that is built into them. For a few people learning that can be more difficult than the process improvement itself.

Sometimes We Have To Choose

A quote from a class I took a long time ago is appropriate here:

“Sometimes you have to choose between ‘being right’ or ‘getting what you want.’”

I can “be right” about insisting that the 5 Questions are being answered correctly and precisely.

Sometimes, though, that will prevent my learner from learning.

Countermeasure

When I first read Toyota Kata, my overall impression was “Cool! This codifies what I’ve been doing, but had a hard time explaining.” … meaning I was a decent coach, but couldn’t explain how I thought, or why I said what I did. It was just a conversation.

What the Coaching Kata did was give me a more formal structure for doing the same thing.

But I have also found that sometimes it doesn’t work to insist on following that formal structure. I have been guilty of losing sight of my objective, and pushing on “correctly following the Improvement Kata” rather than ensuring my learner was learning.

Recently I was set up in the situation again. I was asked to coach a learner who has had a hard time with the structure. Rather than trying to double down on the structure, I experimented and took a different approach. I let go of the structure, and reverted to my previous, more conversational, style.

The difference, though, is that now I am holding a mental checklist in my mind. While I am not asking the “Five Question” explicitly, I am still making sure I have answers to all of them before I am done. I am just not concerned about the way I get the answers.

“What are you working on?” While I am asking “What is your target condition?,” that question has locked up this learner in the past. What I got in reply was mostly a mix of the problems (obstacles) that had been encountered, where things are now, (the current condition), some things that had been tried (the last step), what happened, etc.

The response didn’t exactly give a “Target Condition” but it did give me a decent insight into the learner’s thinking which is the whole point! (don’t forget that)

I asked for some clarifications, and helped him focus his attention back onto the one thing he was trying to work out (his actual target condition), and encouraged him to write it down so he didn’t get distracted with the bigger picture.

Then we went back into what he was working on right now. It turned out that, yes, he was working to solve a specific issue that was in the way of making things work the way he wanted to. There were other problems that came up as well.

We agreed that he needed to keep those other things from hurting output, but he didn’t need to fix them right now. (Which *one* obstacle are you addressing now?). Then I turned my attention back to what he was trying right now, and worked through what he expected to happen as an outcome, and why, and when he would like me to come by so he could show me how it went.

This was an experiment. By removing the pressure of “doing the kata right” my intent is to let the learner focus on learning about his process. I believe I will get the same outcome, with the learner learning at his own pace.

If that works, then we will work, step by step, to improve the documentation process as he becomes comfortable with it.

Weakness to this Approach

By departing from the Coaching Kata, I am reverting to the way I was originally taught, and the way I learned to do this. It is a lot less structured, and for some, more difficult to learn. Some practitioners get stuck on correct application of the lean tools, and don’t transition to coaching at all. I know I was there for a long time (probably through 2002 or so), and found it frustrating. It was during my time as a Lean Director at Kodak that my style fundamentally shifted from “tools” to “coaching leaders.” (To say that my subsequent transition back into a “tools driven” environment was difficult is an understatement.)

Today, as an outsider being brought into these organizations, my job is to help them establish a level of coaching that is working well enough that they can practice and learn through self-reflection.

We ran into a learner who had a hard time adapting to the highly structured approach of the Improvement Kata / Coaching Kata, so we had to adapt. This required a somewhat more flexible and sophisticated approach to the coaching which, in turn, requires a more experienced coach who can keep “the board” in his head for a while.

Now my challenge is to work with the internal coaches to get them to the next level.

What I Learned

Maybe I should put this at the top.

- If a learner is struggling with the structured approach, sometimes continuing to emphasize the structure doesn’t work.

- The level of coaching required in these cases cannot be applied in a few minutes. It takes patience and a fair amount of 1:1 conversation.

- If the learner is afraid of “getting it wrong,” no learning is going to happen, period.

- Sometimes I have to have my face slammed into things to see them. (See below.)

- Learning never stops. The minute you think you’re an expert, you aren’t.

__________________

* “Steep learning curve” in this case means “sometimes learning the hard way” which, in turn means, “I’ve really screwed it up a couple of times.”

* “Steep learning curve” in this case means “sometimes learning the hard way” which, in turn means, “I’ve really screwed it up a couple of times.”

They say “experience” is something you gain right after you needed it.