A client and fellow lean learner today shared a cool extension of the Toyota Kata model for establishing target conditions.

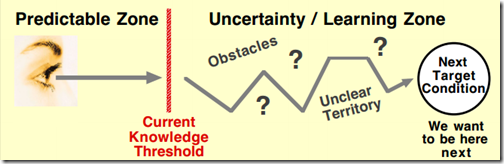

Mike Rother’s Improvement Kata Handbook establishes a couple of key concepts about where a target condition should be set. The key is that the target should be somewhere beyond the learner’s knowledge threshold:

The knowledge threshold marks the point where the process is not yet fully understood. Setting a target inside that boundary is simply a matter of executing a plan, no learning is required.

A target beyond the knowledge threshold is true improvement, because we don’t know how to do it yet. We just have a reasonable belief we can get there.

This is the concept of challenging the learner, depicted here:

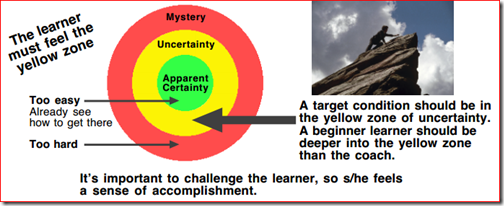

Here is another way to look at it – thanks to Matt – though I have altered the geometry a bit here.

In the “Comfort Zone” we are, well, comfortable. This is the daily routine, things are predictable. As our brains are wired to seek predictability, most people seek out activities they already know how to perform.

Beyond the knowledge threshold is the “Learning Zone.”

We know from the principle of Deep Practice that skill only develops when we are striving to perform just beyond the limit of our capability – on the edge of failure.

It a zone where small mistakes can be made, realized quickly, and corrected immediately for another try.

If, though, we ask someone to do something that he perceives carries a high risk of failure, he enters the “Fear Zone.”

The boundaries for these zones are individual, and are a mix of the person’s skill and knowledge base + his tolerance for risk.

What I like about this model, though, is that can be extended.

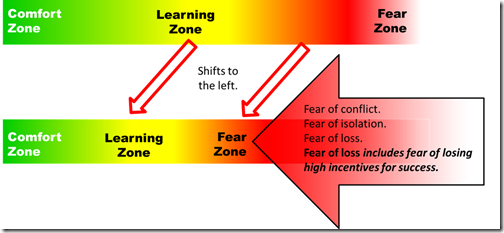

Our brains are incredible simulation machines. We can imagine an activity or event, and feel the same emotional response we would have if it were real.

But we have a heavy, survival based, bias for loss avoidance. Simply put, we have a stronger drive to avoid loss than we do to seek reward. This is why people hold on to investments that are tanking, and remain in bad jobs and unhealthy relationships. The predicted sense of loss is actually stronger than what would actually be felt.

This explains the seemingly backward effect of high stakes incentives that Dan Pink talks about in his book Drive and in this TED Talk. (Skip ahead to 1:50 to get to the main points.)

If the leadership climate sets up fear of loss as a consequence of failure, we have a very strong force pushing the boundary of the fear zone to the left:

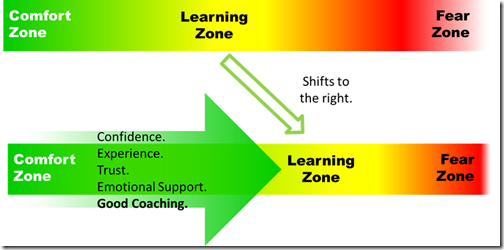

But what we want to do is, over time, shift the learning zone to the right. That is, the team member is comfortable in increasingly complex situations – her skill levels for dealing with the unexpected are much higher.

So how do we get there?

We can look at the highest performing people, and look at the social support networks that nearly all of them have.

If you want performance, you have to (1) remove fear and (2) provide safety for experimentation and learning.

One final note – changing the culture of an organization is not easy, and the appropriate tools to do so are highly situational. You can’t just say “You’re empowered” and expect a transition. More about that in a few days.