The introduction of The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership covers ground that:

- Has been covered before – we know all of this.

- Needs to be covered again, because most people act as though we don’t know it.

Simply put, Liker and Convis (legitimately) feel the need, once again, to let us know the things which reliably fail when trying to build a sustaining culture of continuous improvement.

“So let’s train some Lean Six Sigma experts to grab the tools and start hacking away at the variability and waste that stretch out lead time; this will make us more successful, both for our customers and for our business. What could be simpler?”

What indeed.

I am, once again, reminded of a saying that “People will exhaust every easy thing that doesn’t work before they try something difficult that will.”

The authors cite some of the same things that we have heard before:

- Trying to determine ROI for each individual process step, or each individual improvement, doesn’t work.

- Trying to motivate the right behavior with metrics and rewards doesn’t work.

- Trying to copy the mechanics doesn’t work.

- Trying to benchmark, and copy, a “lean company” in your business doesn’t work.

Yet, even though we have been hearing these messages for at least a decade, actually longer, I continue to encounter managers who try to work this way.

The authors assert, and I agree, that this is the result of people trying to fit Toyota’s system into a traditionally taught management paradigm that is so strong people aren’t even aware that there is a paradigm, or can’t conceive there is anything else.

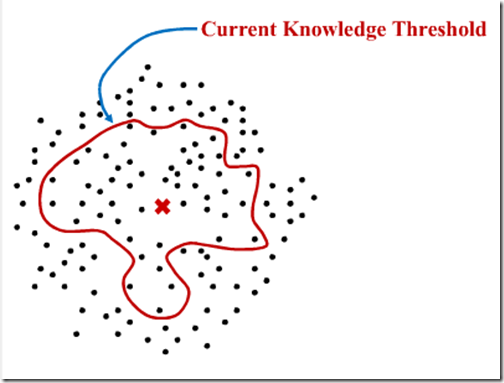

They are stuck inside their threshold of knowledge when the answer is beyond it.

This reminds me of the Edwin Abbot’s 1884 story of Flatland, a two-dimensional world populated by creatures who cannot conceive of “above” and “below” their planer existence.

Although his story is often read by students struggling to grasp models with four, five and more dimensions to them, it is really a story of social change and paradigms.

Our management systems are a “flatland” with Toyota’s system existing in a space that we have to work hard to grasp. We can see pieces of it where it touches ours, but like the creatures in Flatland who only see two dimensions of three dimensional objects, we only see the pieces of TPS that we can recognize.