Mike Rother and Bill Costantino have shared a presentation titled “Toyota Kata Unified Field Theory.”

I think it nicely packages a number of concepts in an easy-to-understand flow.

I want to expand on a couple of points but first take a look at the presentation.

This is a direct URL to the original SlideShare version: http://www.slideshare.net/BillCW3/toyota-kata-unified-field-theory

Challenges and Campaigns

First of all, this presentation differentiates between a “challenge” and the target condition. That is important, and (in my opinion) had not been as clear in Rother’s original book.

I have been advocating setting a challenge, or campaign if you well, for some time. This is where we address a class of problems that are a major issue. Things like:

- Too much cash tied up in working capital. (Which can be expressed a number of ways, such as improving inventory turns.)

- Poor schedule performance – “on time delivery” becomes the theme.

- Quality issues (too much rework, scrap, etc.)

- Our nurses don’t have time to prepare rooms for the next patient.

- Of course, safety can come into this arena as well, as can other issues that impact the organization’s health.

Setting a specific challenge doesn’t mean you ignore the other stuff. You have been coping with it and working around it for years. But you know you haven’t had time to fix everything, so stop believing that you do.

The point here is to galvanize the effort.

Chip and Dan Heath address the importance of setting the challenge in their book Switch (which I have reviewed here). They emphasize the importance of “scripting the critical moves” and “pointing to the destination” so that people have a good grasp of what is important.

Bill Costantino correctly points out that setting the vision, and deciding the theme or campaign, is a leadership function. This can’t be done by your “lean team” in a way that sticks. The discipline required here is for the leaders to maintain what Deming referred to as “consistency of purpose.”

Simply put, to say “this is the challenge” and then continuously ask about other stuff jerks people around and serves only to paralyze the organization until the leaders decide what people should spend their limited time on.

The good news is that it really doesn’t matter. If the organization can focus on One Big Thing long enough, their efforts will eventually touch on the other stuff anyway.

Jim Collins uses different words to make the same point in Good to Great with the “Hedgehog Concept.”

The Path to the Target Condition

One place where I think we can still use some more clarity is in the illustration of the path to the target condition.

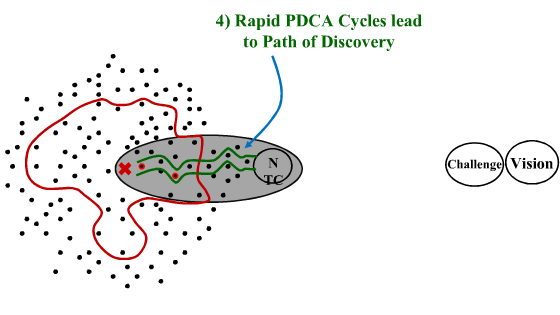

This is the illustration from Slide 20 in the Slideshare version of the presentation:

The presentation (and Rother’s coverage in Toyota Kata) is quite clear that navigation through “the grey zone” is a step-by-step process (kind of like driving off-road at night where you only see as far as your headlights).

The presentation (and Rother’s coverage in Toyota Kata) is quite clear that navigation through “the grey zone” is a step-by-step process (kind of like driving off-road at night where you only see as far as your headlights).

But the “plan and execute” paradigm is very strong out there.

My experience is that people in the field see this illustration, and fully expect the green path to be set out, and the “dots” identified, along with a time line and resources required to get there. It becomes a “project.”

This is a strong symptom of the “delegate improvement” paradigm that we should all be actively refuting.

Let’s look at how I think this process actually plays out dynamically.

Initially we know where we are, we have target condition, so we know the direction we need to go to get there.

We are still inside the red line of the “current knowledge threshold.” Solving these problems is generally application of things we already know how to do, perhaps in new ways.

And having solved one problem, we now identify the next known barrier:

And having solved one problem, we now identify the next known barrier:

Once that one is cleared, we see a couple of choices. Which one?

Once that one is cleared, we see a couple of choices. Which one?

All other things being equal, pick the easiest, and move on. (As we said when I was learning rapid maneuver tactics in the Army – “haul ass and bypass.”)

Up to this point, we have been operating inside the “current knowledge threshold.” Our efforts are better focused by pursuing a clear target objective, but we aren’t really learning anything new about the process. (Hopefully we are becoming better practiced at problem solving.)

Pretty soon, though, we reach the edge, and have to push out the red line. Why? Because we can’t solve a problem we don’t understand. As we approach the boundary, things get harder because we have to do a better job assessing, and extending the knowledge threshold around the problem.

This is the essence of the problem solving process – If you can’t see the solution, you need to better understand the problem.

The process becomes one of progressively solving problems, identifying the next, and expanding our understanding. Once there is sufficient understanding to anchor knowledge and take the next step, do so. Step and repeat.

Putting the whole thing in motion, it looks like this:

The key is that the “green path” isn’t set out as a predictable trajectory. It is hacked out of the jungle as you go. You know you are going, are confident you can get there, but aren’t sure of exactly what issues will be encountered along the way.

The key is that the “green path” isn’t set out as a predictable trajectory. It is hacked out of the jungle as you go. You know you are going, are confident you can get there, but aren’t sure of exactly what issues will be encountered along the way.

Let me apply my “Project Apollo Test” to this process.

Vision: “The USA will be the undisputed leader in space exploration.” Vague, a long way out there, but compelling.

Challenge, Theme: “…before this decade is out, […] landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” In 1961, a serious challenge, but considered do-able based on extrapolating what we knew.

At this point, though, space exploration was exploring a lot of different things. Building a space station, reusable launch vehicles, pretty much the whole gamut was being explored by someone, somewhere. The effort wasn’t focused. The “man on the moon” goal focused it. Every thing was pretty much dropped except solving the problems that were in the way of making Lunar Orbit Rendezvous work.

There were four target conditions that had to be cleared.

Build and test the Big Honkin’ Rocket called the Saturn V plus the infrastructure to launch them in rapid succession.

And they had to answer three questions:

- Can people spend two weeks in space without serious physical or psychological problems?

- Can we build a space suit that lets someone operate outside the protection of a space craft?

- Can one space craft maneuver, rendezvous and dock with another?

Of course each of these objectives, in turn, had lots of smaller challenges. NASA’s effort between 1962 and 1966 was focused on answering these three questions.

In doing so, the threshold of knowledge expanded well beyond the immediate issues.

Yup, I’d say this thinking works, and it scales up.

Why did I go through this little exercise? Because if this thinking can put people on the moon, it is probably powerful enough to move your organization into new territory.

Mark,

Bad link to slideshow or Boeing firewall is blocking, either way couldn’t get Firefox to find it

I just checked it with Chrome, Firefox and I.E.

Firefox did indeed show it as a bad link.

It worked in the other two, so I am inclined to say it is a Firefox problem.

In any case, here is the original link as It got it from Mike Rother:

http://www.slideshare.net/BillCW3/toyota-kata-unified-field-theory

Thank you for a fabulous presentation and direction.

I was impressed with Rother’s work but you have added a huge dimension to understanding why it works. Your ideas fit exceptionally well with understanding work systems as complex adaptive systems and how to approach them.

Daniel Kahneman’s work provides huge support for your front-end. If you haven’t read his newest book, Thinking: FAST and SLOW I recommend it. I predict you’ll like it!

Thanks again.

Regards,

Larry Leach

Thanks so much for posting the presentation. Your break down of the information makes this a great teaching tool. I’m sharing this page like crazy…

One of the thoughts I had with this presentation is that it puts, correctly, a lot of focus on the vision. That’s where most organizations go wrong. It is usually short-sighted (the next quarter) and wrongheaded (focused only on making money for the execs and shareholders, forgetting employees, customers, and other stakeholders).

That is where organizations that survive for centuries get it right.

Good Work! I like how you have translated the unified theory into some real life examples. the animation helps demonstrate the approach through time – i love it! Also I like the idea that typically you start the problem solving within the threshold of knowledge and then break into new knowledge. I wonder whether that new knowledge is a continual threshold increase or if there are moments where the threshold is increased and several obstacles are seen versus being revealed one obstacle at a time. thoughts?

Jason

I think we can always see many more obstacles than one. The question is not “What obstacle can I see” but rather “What obstacle should I work on?”

“One problem at a time” (ideally, one small problem) is a mantra I find myself repeating quite a bit to people who want to find a Single Solution to Everything. I suppose that might work often enough to reinforce the behavior (kind of like a payout from slot machines), but in the long haul, I prefer serial-problem-solving.

What I like about Toyota Kata’s approach is that “What problem should I work on?” is an inherent part of the process, rather than outside it.

I contrast that with the way I was taught “problem solving” where the first step involved “select a problem to work on” using tools like the Impact-Feasibility matrix and (gasp) multi-voting. These tools, of course, are necessary when the team is given no context or direction whatsoever other than “go find problem to solve.”

The way “kaizen events” are planned often isn’t much different. The workshop leader heads out to find an opportunity, sell it to management sponsorship, then assemble the team to go work the issue. This (not surprisingly) is how I was originally taught to do this as well, we called it a “Scan and Plan” and the class included several hours on “contracting with management” to gain support for the proposed activity. Same thing, different wrapper.

Mark, your piece really clarifies TK for me! Thank you for that. Especially the challenge setting part was a new insight.

I thought a have:

Don’t you think the “grey zone” within the knowledge threshold is clearer than outside the threshold? You already know how to solve the problems within, you see the answers. So shouldn’t the grey zone start outside the threshold? And therefore, would it not be possible to attack problems (in True North direction) within the knowledge threshold in a more planned, projectapproach way since this part of the path is more “certain”? Haven’t come up with a completely satisfying answer yet so very much interested in your thoughts….

Jeroen –

Given the model in Bill Costantino’s graphic, I would tend to agree that “grey zone” problems that are within the knowledge threshold would be easier to solve, though that doesn’t mean they ARE solved.

Nor, I believe, does it mean that we know which specific problem needs solving next until the path is starting to get carved out. I believe the key point of the original presentation was that (1) we don’t have the resources to solve all of the problems, even those within the knowledge threshold. (2) Setting a target objective allows a direction to be set, and a logical sequence for solving those issues to emerge.

Further, ironically, the “solution” would likely be different if I am solving the problem because it is blocking progress toward a specific objective, vs if I am solving it because it is there.

I really enjoyed the presentation. I am have read the Toyota Kata a few times and am still struggling with bringing it into reality. My environment is in R&D Product Development. If you have any suggestions on helping make the rubber hit the road I would appreciate it very much.

Matthew –

I took the webmaster’s prerogative here and replied by email.

Mark

Mr. Rosenthal, we would like to share this video with key leaders in our company and wanted to know if there is a way to make it viewable w/audio on an ipad. Any help would be appreciated. Thank you!

Replied by email.

I cant get the sound with the slides on the unified filed presentation. would someone send me the presentation if possible.

thank you

colin.roach@aol.com

Colin –

The link below the embedded version takes you right to the Slideshare site.

You should be able to download it from there, though you probably have to join Slideshare to do it.

I just tested it, and everything works fine, though Firefox has a history of having problems. If you are using Firefox, you might try it in I.E. or Chrome.

Hi …

Is there any way for me to get hold of the audio as suggested, please? I’d really like to hear the presentation, however, I can’t seem to get the audio working through either of the links provided.

Thanks in advance, and thanks for sharing this great resource!

Based on the Slideshare comments from a couple of years ago, apparently the sound is no longer there. I’ve edited the post accordingly. As it isn’t my presentation (Bill Costantino made it) I can’t fix the sound.

Thanks for the update, Mark. I eventually found Bill’s presentation on YouTube – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqZOu1D639Q … I hope this helps anyone else seeking this wisdom.

Thanks again for taking the time to reply.

Andrew – Thanks for the YouTube link. I updated the post to feature the video.