Last fall I got to spend another week hanging out with the awesome team at Menlo Innovations in Ann Arbor. My last visit there was scheduled for early April 2020… but we probably all know what happened back then.

I am saying all of that because I am going to use their project management system as a benchmark in this article, and I am most assuredly not an unbiased observer. Maybe I was the first time I spent time there, but today they are friends.

What makes Menlo’s project management system stand out to me is captured in the title of this post: Their project management system and their daily management system are one-in-the-same. In retrospect, I can’t think of any other way that project management would be effective.

Getting Stuff Done

In spite of the wishes of some business leaders, there are only so many hours in a week, and there are only so many people available to get things done.

People are busy on stuff. Giving them more to do means something else is not going to get done. The very foundation of Menlo’s culture is making absolutely sure these conflicts are resolved by removing all ambiguity around what is the next most important thing at any given moment.

The other thing their process accomplishes is absolutely eliminating informal scope creep. Rich Sheridan calls this “hallway project management.” It sounds like this, “Hey Mark, I know you’re busy, but do you think you might be able to do this thing for me?” If I answer with an open “Yes,” I have just signed up to do something I may, or may not, have time for. It is now up to me to decide whether it is more important than other things I need to get done. Ultimately that means I have to decide what is not going to get done today.

Who makes that decision in your organization? The decision of what doesn’t get done? The decision of what gets done instead of working on the Main Thing? If that is left to the individual software developer, the individual design engineer, then does management later second-guess that decision? If so, this is the very opposite of “Respect for People.”

Another fundamental principle is that a person cannot actually work on more than one task at any given time. What we call “multitasking” is actually quick steps of starting, stopping, figuring out what task to work on next, starting that, etc. I can’t simultaneously work on this post and pay attention to someone else.

There is a non-trivial time and attention overhead involved every time continuity must be regained. That discontinuity also creates potential for quality issues like leaving things out.

Having a pile of tasks to work on all at once also makes it easy for a task to keep getting pushed off until the time left to do it is insufficient, and can conceal problems that get in the way of the work going smoothly

Menlo’s System

(At least my interpretation of their system.)

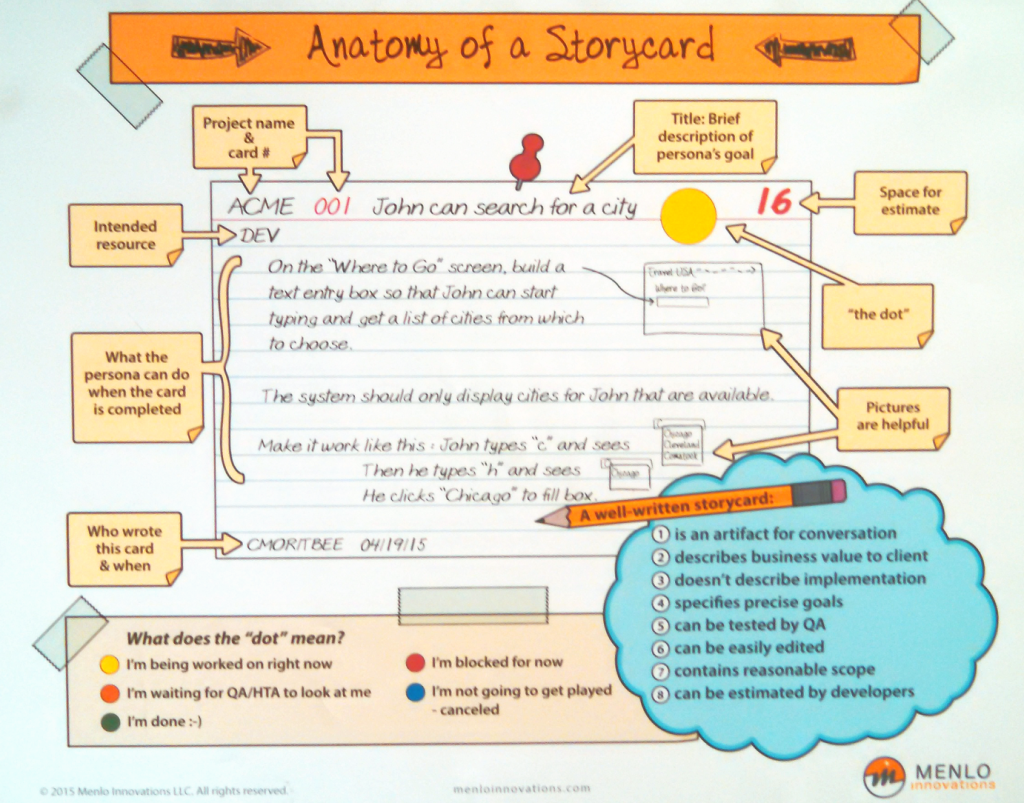

Like any project management system, Menlo’s up-front planning process breaks down the overall project into individual tasks, things that need to get done to make progress. They document those tasks on “Story Cards” which are physical cards that each represent a single feature to build into the software. One story card represents one task that advances the project.

One key feature of a story card is that there is little ambiguity. Adding to that, it is a core part of Menlo’s culture that if someone does encounter ambiguity the response is asking, not guessing.

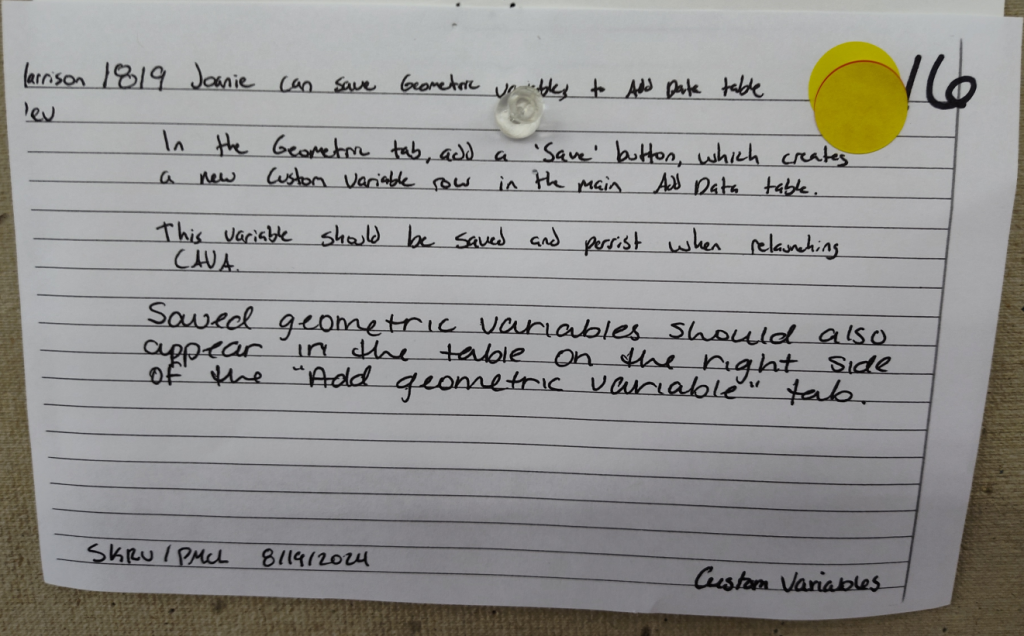

Here is a “live” story card I photographed (with their permission) last fall:

Estimating Time

In the upper right corner of a story card is the estimate in hours. Both of the above examples happen to be 16 hours.

There are two critical keys here.

- The people who are going to do the work are the ones who make the estimates.

- Those estimates are not second-guessed or adjusted by others.

These estimates are based on, “Once we start on this, how long will it take to get it done.” The assumption is that there is no multi-tasking. This isn’t “When can I finish it.” It is “How much time must I spend to do it.” That may be different from what you are used to in your projects, but it is critical to make this work.

Estimates Are Wrong

Menlo generally does a pretty good job with this because they collect “actual actuals” as they are working. That gives them a good reference library of analogous work they have done in the past.

But, that being said, the estimate is made when the actual knowledge of what will be required is at its lowest. This is true for ANY time estimate, no matter where or who you are.

In many organizations a time estimate becomes a firm commitment and, worse, there are negative consequences if the task ends up taking longer than estimated. This inevitably leads to people padding the estimate, which then leads to the game of project managers cutting the time allotted. That does not happen at Menlo. Rich Sheridan tells the story of why that does not happen there far better than I can in this clip from a talk he gave some years ago. (Link here for the entire talk)

(As an aside, the first time I visited Menlo (for a week), I actually witnessed some fairly bad news get shared in the daily standup. The response was a quick huddle, lasting a couple of minutes, between the developers and the project manager immediately after the daily standup to discuss communication with the customer. Then everyone got back to work.)

Time Bounded Work Planning

Menlo’s basic project management cycle is a work week (typically 5 days). Menlo calls this an “iteration,” but the jargon doesn’t matter. Each week they:

- Review the cards (tasks) that have been completed.

- Decide with the customer what cards will be scheduled for the next week.

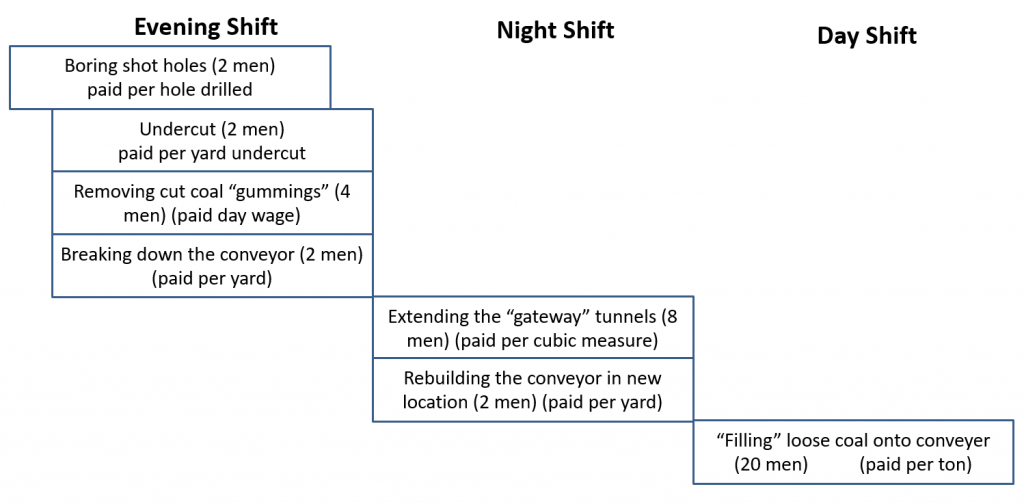

This is irrelevant to you at the moment, but Menlo’s developers work in pairs. One pair working for one week is the basic unit of capacity for planning purposes.

There are 32 productive hours in their week, plus 8 hours of overhead such as standing meetings, project support tasks, reviews with the customer. Thus, for one pair, they can schedule 32 hours worth of cards. No more.

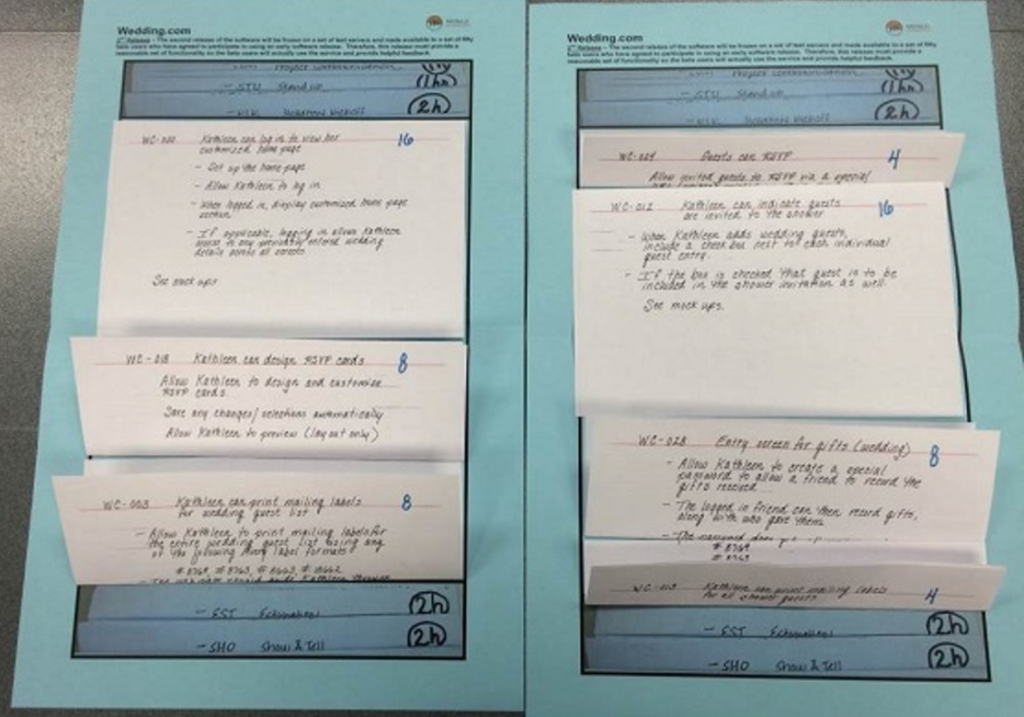

The process they use is ludicrously simple. They call it “planning origami.”

For each pair of developers (what you might call a “resource” in traditional project management terms), there is a physical sheet that is sized to represent 32 hours.

Using photocopies of the story cards – the size of one card represents 16 hours.

If the card is estimated at 8 hours, they fold the card in half. A 4 hour card is folded in half again.

A 32 hour card is taped to a full sheet of paper that takes up the entire 32 hour space.

At Menlo the customer is the one making the decision about what gets done, and what does not get done, this week. THEY must choose the cards (with help from the Menlo, obviously) and fit them into the planning sheets which represent the resource capacity available to them.

If someone (the customer) insists on adding something, something else has to come off. The capacity is fixed. What gets done with that capacity is entirely up to the customer.

THIS IS THE ONLY WAY WORK GETS INTO THE “TO DO” QUEUE.

Thus, everyone knows what is expected to get done and, more importantly, what we are NOT going to work on this week.

Now… sometimes things go really well. The customer can prioritize “pull ahead” cards in case things go faster than expected (underrun the estimates), and there is additional capacity.

Daily Management

All of this was to set up the daily management system.

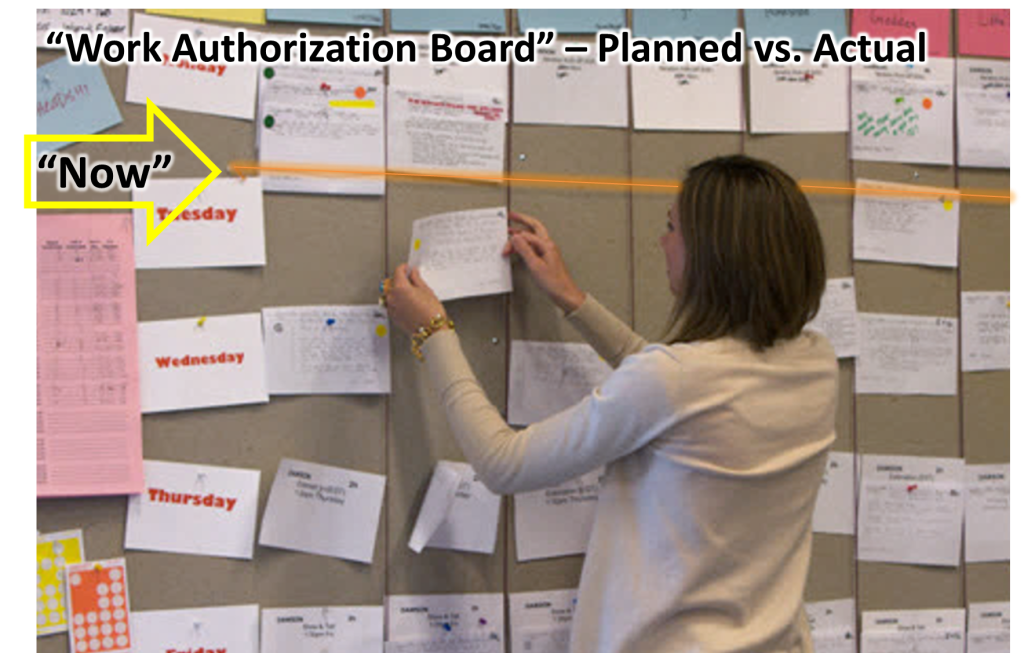

At the start of each week, the planned cards are placed, in order, on the “work authorization board” which is a tack board on the wall. The name is literal. This is the work that is authorized to be done this week.

But this is more than a task list. The work authorization board is a live reflection of what is actually happening vs. what was planned.

Each column on the board represents one unit of capacity, in their case one week of work for one programming pair team.

The developers work on the cards from top to bottom, in order.

When they start work on a card they put a yellow dot on it.

When they think they are done, they put an orange dot over the yellow dot. This signals the Quality Advocate to verify that the code accomplishes the intended function. If it passes, the card gets a green dot and the developers start on the next card.

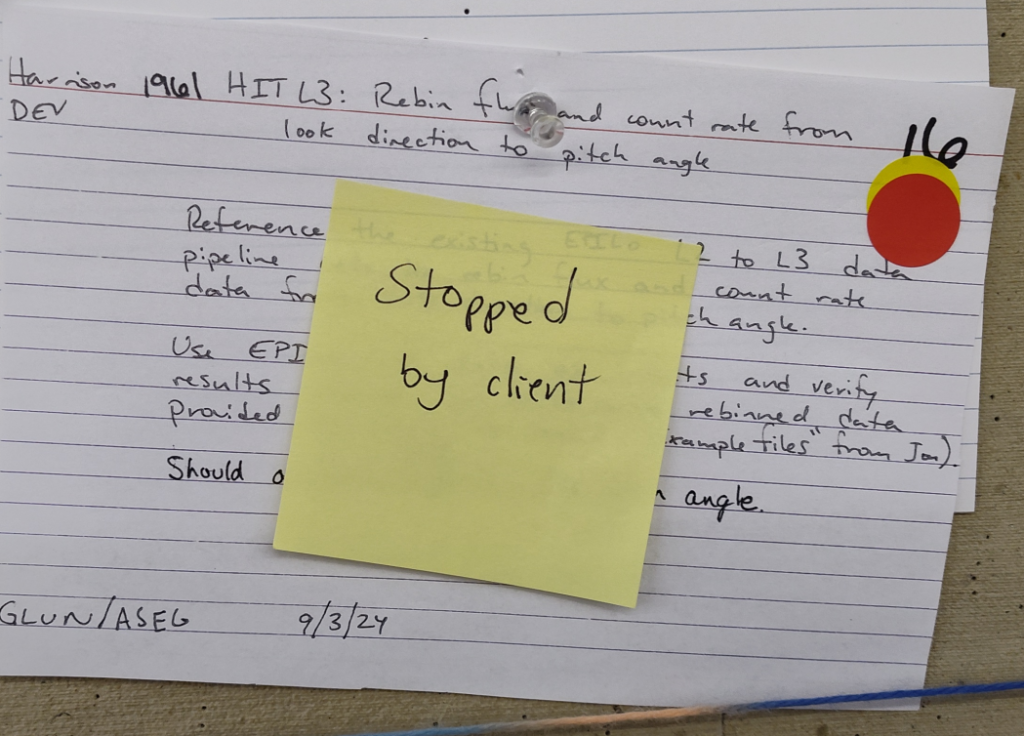

If something is stopping progress, the card gets a red dot (and the Project Manager is informed).

Each day’s estimated work is clearly identified. There is a piece of yarn across the board that is moved down each day. Thus, if there are incomplete cards above the yarn, they are behind. If there are completed cards below the yarn, they are ahead.

Nobody has to ask a pair what they are working on. It is the card with the yellow dot on it. Status is clear to all.

If you were to visit Menlo with the above information, you would be able to grasp the status of all of their projects just by walking around the perimeter of the work area.

It. Is. That. Simple.

This process manages the project at a low level of tasks rather than more abstract “milestones.” Yes, there are milestones, but the level of management is every day. This allows the people who are doing to the work to tightly manage the progress of their work. The Project Manager is freed up from trying to keep track of everything simply because it is insanely easy for anyone to see the status in real-time during the course of any given week.

Accountability

There are two basic rules for accountability here. Rich goes through them in the video embedded above.

- The developers will never, ever, get any negative feedback, real or implied, for reporting that they blew an estimate and just discovered something is going to take a lot longer than they thought. This is accountability from management, which MUST come before asking for accountability from anyone else.

- The developers must inform the Project Manager immediately when they realize something will take longer than they thought.

Rule 2 will not work without Rule 1 because otherwise people would pad estimates, not report bad news, or otherwise try to protect themselves.

This measures TASKS, not milestone dates. If the tasks get done, we will hit the milestones. Missing a milestone is too late to recover.

There are still milestones, but they day-to-day work is reality, and milestones may well be adjusted to reflect reality as everyone learns more. Remember, project milestones are established when we know the LEAST about what work is actually entailed! That is true for ANY project management system.

Handling Emergent Work

If someone approaches a developer with a “can you just do this too” kind of task, the developers have a practiced, rehearsed, response: “Yes, absolutely. Let’s get it on a card and estimated so we can get it into the schedule.”

Thus, if something is going to be added, something else has to come off. The work authorization board only holds 32 hours of cards / week for each programming pair.

More Management Accountability

Management is accountable to stand behind the system. This, again, is demonstrating respect for people. Management refuses to override “just this time,” There is not time for “just one more little thing.”

Weekly Cadence

At the end of each week, the developers and the customer meet to review progress. Menlo typically has the customer demonstrate software features back to the developers. This gives the developers better feedback on whether or not the customer’s needs are being met. It also validates the design decisions about how intuitive the user interface is.

Then the Planning Game repeats.

So based on what is actually done and what is actually remaining, the weekly planning process is repeated for the next week.

Back to the Title: Project Management IS Daily Management

What this system does is tightly link project management to actual, daily, task execution. This is the key to making it work.

The only way to hit the long-term goals is to track execution at a level of granularity that allows you to see problems and delays while they are small enough to deal with, and have a robust system for actually dealing with them.

If your project tasks have vague definitions of “done” and estimates based on completion dates you are inviting additional work to creep in unnoticed.

Menlo’s system acknowledges the one thing that is hard: There is only so much capacity to get things done, and we must plan to that limitation.

Doing that requires management discipline to the process, and that generally is the hardest part.

Further Reading for Context

I highly recommend reading Rich Sheridan’s book Joy, Inc for the back-story of why it was important to create this process in the first place. (The link as an Amazon affiliate link, if you choose to buy the book I’ll get a small kickback, no cost to you.)

Question for YOU

How does your project management process stack up against this benchmark? Leave a comment – let’s get a discussion going, there are a couple of thousand of you out there subscribed to these posts.