Lately the term “socio-technical system has been starting to show up more and I thought this would be an opportunity to weigh in on what I think it means.

Though the concept has been around since at least 1951 (see below), I think I have tended to “bleep over” the term as jargon without giving it a lot of thought. I don’t think I am alone in that.

People who try to describe the meaning tend to describe a system “that integrates the social and technical aspects” or words like that.

I would posit that it goes much deeper, and we “bleep over” the concept at our peril if we want our organizations to function well.

The Origin of Social-Technical Theory

*Up through the 1940s, coal mining in the UK was largely pick and shovel work aided by drills and, sometimes, explosives. A work crew typically consisted of three to half a dozen men (and they were all men) who were task organized to strip the coal off the seam face, shovel it into mining carts, and move those carts to the transport system.

These teams were distributed through the mine, and because the distance and working conditions really precluded a lot of supervision, the teams largely oversaw their own work.

Since each team worked independently, the system as a whole could easily accommodate the simple fact that in some spots the coal is harder to dig out than in others.

(If you want to get more of a feel for the work and working conditions, check out the photos in this Daily Mirror article: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/real-life-stories/britains-last-deep-coal-pit-7000879)

The work also met every definition of “difficult, dirty and dangerous.” That work environment, though, created a social bond among the team members as they worked together to accomplish the task of “mining coal.”

The system was not without its problems, however. The social structure was built around loyalty to the small work team. When “trams” (coal carts) were in short supply, for example, the “trammers” would horde carts to optimize their team’s performance at the expense of other teams being limited by the number of carts available.

This all changed shortly after WWII.

The Long Wall Method

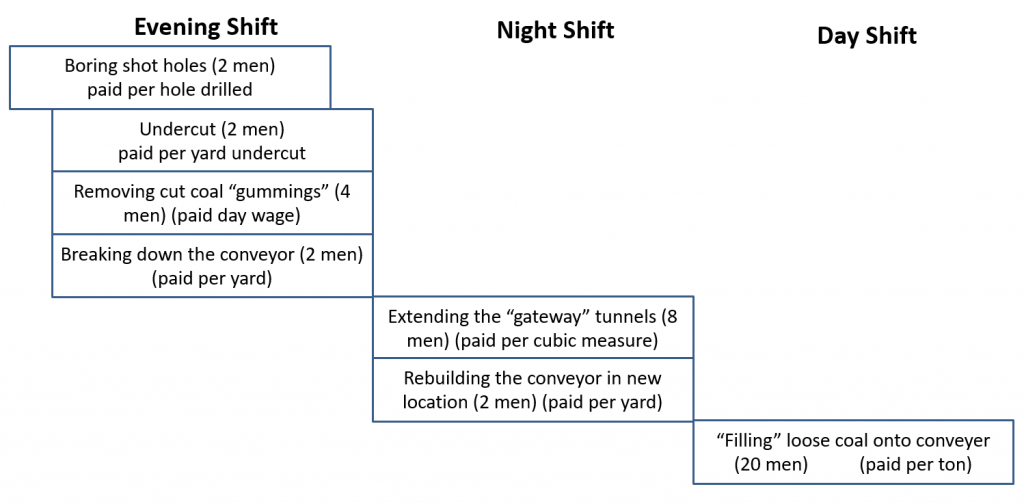

In the late 1940s the industrial engineers turned this craft production system into a factory system with the tasks divided between three shifts.

The process would begin on the evening shift. They would drill blast holes along the top of the coal seam, then dig an undercut about six inches high at the base to allow the blast to drop the coal. This would be done along a long (up to a couple of hundred meters) face of the coal seam. (Hence the name “long wall mining.”)

Meanwhile another team would break down the conveyor system that ran parallel to the coal face in preparation for moving it forward to position it for removing the loose coal.

Then night shift had two teams. One would extend the “gateway tunnels” at either end of the coal face. This was a crew of 8 men. Simultaneously another team would rebuild the conveyer in the new position.

Once all of this work was done, the shots would be fired, dropping the coal into a pile along the coal seam face.

Day shift would take the loose coal and transfer it to the conveyor system to be taken out of the mine.

Yes, this is an oversimplification, but it suffices for this discussion.

On paper, this process was far more efficient.

In practice, though, things did not go smoothly.

“Isolated Dependence”

Looking at this work breakdown, the first two shifts are prep work. Only the day shift, the “fillers,” actually get the coal out of the mine. But their success was entirely dependent on how well the first two shifts did their jobs. If everything was not “by the book” then the fillers would be significantly hampered. Since they were paid by the ton of coal extracted, there was more at stake than just a sense of accomplishment.

If the previous shifts ran into problems – such as a “shot” that failed to separate all of the coal from the roof of the seam, or harder material, etc. these inconsistencies slowed down the “fillers” and made them less successful. If the conveyor was not completely or correctly assembled, they could not begin work until this was corrected.

Because management pressure was on the key performance indicator – the rate of coal extraction, and because the “fillers” were paid by the ton of coal extracted, this created resentment between the “fillers” and crews on the other two shifts, as well as conflicts with management which the working crews began to regard (with ample evidence) as disconnected from the realities of their work.

Then, if the “fillers” were too far behind at the end of their shift, that would delay the start of the next cycle and things spiraled downward from there.

Productivity plummeted. The study I am citing here was commissioned to determine why. Their conclusion, in short, was that the new work organization was built around the paradigm of a factory assembly line without regard for the variation of geology. Success of the three shift cycle depended on each shift meeting a rigid schedule, but that schedule did not account for the simple fact that coal seams are not uniform.

In addition, the work organization destroyed the social structure of the mining crews. Their success was dependent on people they no longer saw or interacted with. The oncoming filler shift, in particular, would be confronted with all of the obstacles left by the previous two shifts. As their resentment for being unsupported built, their willingness to put in any extra effort dropped to zero.

Again – this is an oversimplification. If you want to read the full paper there is a link at the end of this post.

Oversimplification or not, however, the effect was stark. The social structure of the organization was driven to fundamentally change by alternations in the technical structure of the work. Quoting from my source material* :

The effect of the introduction of mechanized methods of face preparation and conveying, along with the retention of manual filling, has been not only to isolate the filler from those with whom he formerly shared the coal-getting task as a whole, but to make him one of a large aggregate serviced by the same small group of preparation workers.

The work design was based on a mechanistic view that ignored the how the social structure impacted the performance of the team.

The Mechanistic View

By the turn of the last century we thought we had the ways of the universe pretty well understood. Hundreds of years (thousands of years in some early societies) earlier we had the ability to predict the motion of the stars and planets – to the point that we could build machines that were analogues of their movements.

The prevailing model in psychology was classical conditioning which, in essence, said that behavior is an almost algorithmic learned response based on previous positive and negative reinforcements.

This mechanistic model leads to a belief that we can carefully design the machine and people’s work within the machine can be carefully designed and shaped through rewards and consequences.

And as long as everything, and every one, works as they are supposed to, it’s all good. If a machine malfunctions, we fix it. If people don’t follow procedures, we “motivate them” with incentives.

This model prevails even today and even colors our teaching of continuous improvement. One of the places we need tend to inherently adopt a mechanistic view is when we use the word “system.”

The Mechanistic View of “System”

In today’s world, when people talk about “the system” they are often referring to an information system of some type. Common examples are an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, or an Electronic Health Records (EHR) system. And these information processing systems do tend to shape how the organization functions, for better or for worse.

So when people talk about a “system” I think the reflex is to think of the system as a machine that is carefully designed, built, and tuned to perform a particular function or behave in a particular way.

And people tend to assume that once it is working, it will continue to work so long as it is maintained to be kept in the same condition.

This thinking often extends to the people as well. They are often viewed as servicing “the system” – providing it with information, and following the instructions it gives. (this is particularly true in ERP / MRP environments.) Everything is part of a machine, and as long as everyone does their jobs, and the equipment functions as intended, then it all works.

In practice, though, these systems tend to isolate people from one another, or into small single task groups in much the same way as happened in the coal mine.

The Mechanistic Paradigm at Work

The reason I explained all of this is so we can look at our own workplaces through this lens. The crucial question is: Do the work structures and systems support or hamper the social structure of effective teamwork?

Let’s take another look at those ERP or EHR systems. Without the interaction with and the interaction between the people who use them, those “systems” are inert. They do nothing. The mechanistic paradigm, though, tends to look at people as performing a task to serve or enable the system. Instead, we should look at the information system as a tool that should enable people do to a job they otherwise could not.

On the Shop Floor

The sign says “Hearing Protection Required.” The reality is that it is impossible for more than 3 or 4 people to have a conversation on the shop floor, as they are shouting to be heard. The final operation is highly automated, each machine has two people working in isolation, even from one another for the most part. In addition, the machine crews are isolated from one another, both by distance and by the noise level.

The machine operator is measured on his hourly rate of production vs. a standard expectation.

Meanwhile at the opposite end of the building, the production scheduling team works to carefully orchestrate the availability of packaging materials, purchased components, as well as scheduling each phase of production so work is available for the next step.

They do all of this with their ERP system and every day they create orders to issue components, production orders to the various areas in the shop, and purchase orders to their suppliers. They adjust priorities at least daily, based not only on lead times and changing customer requirements, but also on the reality of what has actually been produced, or not, up to this point. Items are early, they are late, production runs ahead, though mostly behind, the scheduled intent.

Everyone is frustrated. The planner / schedulers because production never seems to make what they planned. And production because scheduling never seems to schedule things that can be made with the available materials, etc. Shortages are discovered, an ad-hoc plan is created to keep things moving – but that may well consume components that were earmarked for something later in the week, and the cycle continues.

To make things even more interesting, the planner / schedulers are using production capacity numbers that they know are higher than reality. They are under pressure to put in unrealistic numbers because the real numbers would make the site’s cost estimates too high and attract scrutiny from corporate.

This means “the system” produces schedules that cannot be met by actual production even if everything else works, which, in turn, means continuously over-promising, under-delivering, and adjusting priorities.

Though the work is very different, we have a social structure not unlike the British coal mine.

This is what “isolated dependence” looks like in today’s work environments. If you are seeing blame casting and conflict between groups who are dependent on one another you likely have a similar situation in your organization.

Counter-Productive Response

Unfortunately the typical management response is to increase monitoring, control, incentives, “accountability” on individual parts of the process rather than looking at the entire system.

These things tend to increase the sense of isolation and frustration as they can create a sense of victimhood between the separate groups. For example, in the above situation everyone there told me that they used to have pull system on the factory floor, and it had worked really well, operated predictably, and gave them a lot more insight into what was actually happening. But some time ago a new management team wanted to track everything in the computer “for control” so the current system was installed.

Ironically, that management team had turned over, but for whatever reason people were very reluctant to return to what they knew had worked in the past. But I digress.

The Implications

Human beings are innately social. In any organization, or casual group trying to get something done, people develop webs of social networks. The more they can interact, the more everyone stays on the same page.

There are a few things we can do to reinforce this.

Bring People Together

And I mean bring them together literally, physically. Rather than just confronting one another in the morning meeting, have them literally work side-by-side with the common goal of a smooth process.

Have a Shared, Objective, Truth

Eliminate the need to ask or query “status.” Eliminate the one person who knows the big picture. Get the truth out there in the open– literally, physically. (See a trend here?)

In a well managed operation I nearly always find rich “information radiators” that are an inherent part of the process itself (rather than being a display of information that was input just so it can be displayed). This information is not simply a passive display. It is actively used by the people doing the work to they know where they stand, what comes next, and when they need to raise a concern.

A classic example of this is a heijunka or load-leveling box. The cards, or work orders, or pick tickets, are placed in slots that are based on the time that work is expected to start if everything is working normally. Thus it is insanely easy to spot if something is getting behind, long before it would show up in the daily production report. Menlo Innovations’ Work Authorization Board does the same thing.

The goal is for conversations to be about “How to respond” rather than discussions about “what is happening.”

This is really the purpose of nearly every “lean tool” — to ask, and answer, two key questions:

- What should be happening?

- What is actually happening?

and then invite a conversation about any difference between the two.

The fact that “we have made 234 widgets” is meaningless without a point of comparison of “how many widgets should we have made up to this point?” The goal is to invite curiosity and foster actual conversations, and eliminate debates about what should be and what actually is.

But more often, this is what I most find lacking. People well tell me they can easily query status, look up individual orders, but even then there is rarely a timely comparison between “nominal” and “actual” in that information. Even if status can be queried, there is often a lack a “compared to what?” Or worse, the status is abstracted from reality, for example, measured in “earned hours” or some other financial metric. Often “ahead or behind” is not known until the end of the day… or the week, or sometimes even the month. The greater the lag, the bigger is the scramble to make up production with overtime.

So here is question #1 for you: If I were to ask you, right now, “Is this operation ahead or behind?” could you tell me? Can the people who are actually doing the work tell me? And by “tell me” I mean immediately, without having to go research or launch some kind of query.

Another version of this question is, “How far behind do you allow yourself to get before you actually know there is a problem?”

Social-Technical

So what we have is a technical aspect of a process that is deliberately designed to support meaningful social interactions between the people responsible for carrying out the work and accomplishing the overall task… as a team. We bring people together rather than isolating them from one another.

This is hard – Yup.

And these principles run against management “best practices” that have been taught since the 1920s.

Where to start? If any of this seems impossible, work on trust. Think about this – Why would people be reluctant to display an objective truth without the ability to first qualify it?

Why would people be reluctant to create a true dependent relationship with another department?

All of these things come down to a culture of self-defense because people feel a need to protect themselves from something or someone. Even if that force is long gone, the effects of leadership-by-fear linger, sometimes for many years, unless you take proactive and direct steps to eliminate that fear.

So… if this seems hard, work on that first.

* The original study of the interplay between social structure and work organization and technology looks to be the 1951 paper “Some Social and Psychological Consequences of the Longwall Method of Coal-Getting: An Examination of the Psychological Situation and Technological Content of the Work System” by E.L. Trist and K.W. Bamforth

Excellent article and summation of the early work on socio-technical work redesign as led by the folks at Tavistock.