When I landed in Detroit last week to visit Menlo Innovations, Mike Rother picked me up at the airport. As soon as I settled in to the passenger’s seat, he handed me my long-anticipated copy of his new book The Toyota Kata Practice Guide. That is the first disclaimer here. The second disclaimer is that last winter he asked if I would do him a favor and take a look through the manuscript with a red pencil. Um… YEAH!

When I landed in Detroit last week to visit Menlo Innovations, Mike Rother picked me up at the airport. As soon as I settled in to the passenger’s seat, he handed me my long-anticipated copy of his new book The Toyota Kata Practice Guide. That is the first disclaimer here. The second disclaimer is that last winter he asked if I would do him a favor and take a look through the manuscript with a red pencil. Um… YEAH!

Thus, I can’t say this post is an unbiased book review. Quite the opposite.

What I am going to do here is go through the book and alternately share two things:

- Why I think this is a great read for anyone, no matter your skill level or experience with Toyota Kata.

- Reflections on my own experience that may have been amplified as I went through it.

The other caveat I really have to offer is this: I have the hard copy of the book. I am absolutely referring to it for the content I am citing. That being said, I drew a lot of the deeper insights I am reporting when I was parsing the manuscript. That was much more than “reading” as I had to really think about what the author is trying to say rather than just read it. If you are serious about learning, I suggest you take your time as you, too, go through the book. Don’t just read. Parse.

And a final disclosure: if you click on the links mentioning the books, it will take you to the Amazon.com page. If you choose to buy the book, I get small affiliate kickback that doesn’t affect the price you pay.

A Bit of History: Toyota Kata has Evolved

From my perspective, I think Toyota Kata as a topic has evolved quite a bit since the original book was published in 2009. The Practice Guide reflects what we, as a community, have learned since then.

As I see it, that evolution has taken two tracks.

1. More Sophistication

On the one hand, the practice has become more sophisticated as people explore and learn application in contexts other than the original industrial examples. Mike Rother and Gerd Aulinger published Toyota Kata Culture early this year. That book provides working examples of vertical linkage between organizational strategy and shop floor improvement efforts. Most of the presenters at Lean Frontier’s recent online Kata Practitioner Day were describing their experiences applying what was outlined in that book. Last year’s KataCon featured a number of presenters who have adapted the routines to their specific situations, and we have seen the Kata morph as they are used “in the wild.” This is all OK so long as the fundamentals are practiced and well understood prior to making alterations – which brings us to the second point.

On the one hand, the practice has become more sophisticated as people explore and learn application in contexts other than the original industrial examples. Mike Rother and Gerd Aulinger published Toyota Kata Culture early this year. That book provides working examples of vertical linkage between organizational strategy and shop floor improvement efforts. Most of the presenters at Lean Frontier’s recent online Kata Practitioner Day were describing their experiences applying what was outlined in that book. Last year’s KataCon featured a number of presenters who have adapted the routines to their specific situations, and we have seen the Kata morph as they are used “in the wild.” This is all OK so long as the fundamentals are practiced and well understood prior to making alterations – which brings us to the second point.

2. Better Focus on Kata as Fundamentals

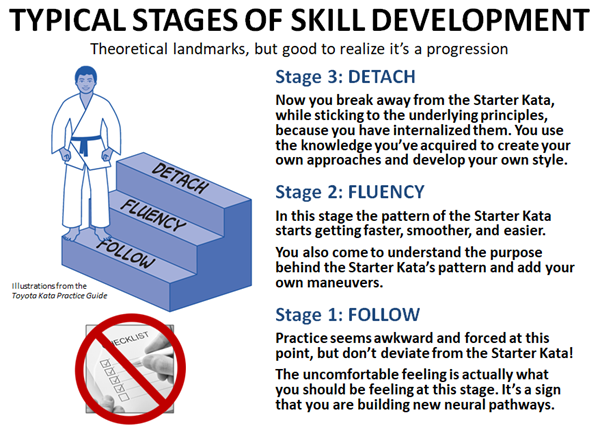

The other evolution has been a better insight that the Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata are, in Mike Rother’s words, Starter Kata. They aren’t something you implement. They are routines to practice as you develop the underlying skill.

If you go to a Toyota, or a Menlo Innovations, you won’t see them using Toyota Kata. They don’t have to because the routines that the Kata are designed to teach are already embedded in “the way we do things” in organizations like that.

We use the Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata to learn so that, at some point in the future, we too can create a culture where the underlying thinking is embedded in “the way we do things.” You don’t have to think about it, because it is a habit.

Rather than being a fairly high-level summary of the research findings (as the original book was), the Practice Guide is what the title suggests: A step-by-step guide of how to practice and what to practice.

The Toyota Kata Practice Guide

With all of that as background, let’s dig into the book.

The book is divided into three discrete sections. I’m going to go through the book pretty much in order, with the section and chapter titles as headers.

Part 1: Bringing Together Scientific Thinking and Practice

The first part of the book is really an executive summary of sorts. It is an excellent read for a manager or executive who wants better understanding of what this “Toyota Kata” thing you (my reader here) might be advocating. It sets out the fundamental “Why, what and how” without bogging down in tons of detail.

Scientific Thinking for Everyone

This is the “Why” and “What.”

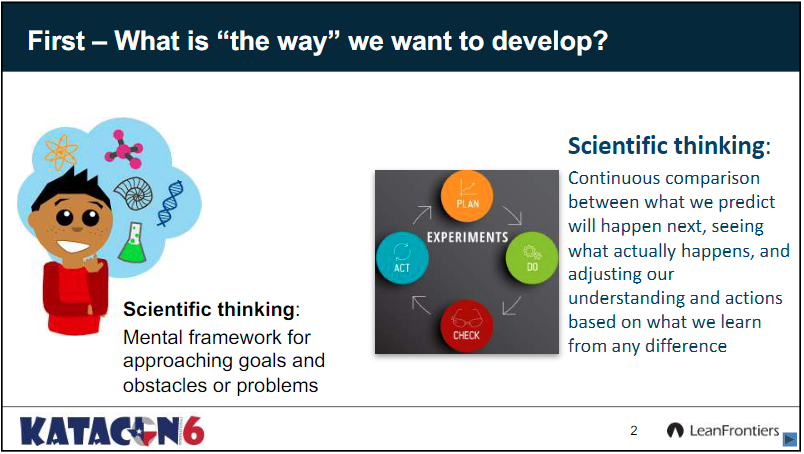

In the first chapter Mike Rother makes the case that “scientific thinking” is the meta-skill or habit that found in most (if not all) learning and high-performance organizations. I agree with him. I believe organizations with an innate ability to reflexively apply good scientific thinking are the ones who can readily adapt to changes in their environment. Those who cannot are the ones who keep doing the same things in the face of evidence that screams “Change!”

The next key point is that “scientific thinking” is not the default habit of the vast majority of adult humans – for lots of good reasons leading to our survival as a species. It is a learned skill.

Learning a skill requires practice, plus knowing what and how to practice. The Improvement Kata provides a pattern for practice as well as initial routines to follow in order to get the fundamentals.

And that point is what separates the Practice Guide from the vast majority of business books. Most business books speak in general terms about principles to apply, and ways you should think differently. They are saying that “you need to develop different habits,” and even telling you what those habits should be, but come up short on telling you how to change your existing habits to those new habits.

Thus if you, the reader of the book, are willing to say “I want to learn this thinking pattern,” as well as say “… and I am willing to work at it and make mistakes in order to learn,” then this book is for you. Otherwise, it probably isn’t. That’s OK.

For the rest of you, read on.

Chapters 2, 3 and 4 go into increasing depth on the process of “deliberate practice” how the structure of the Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata supports it.

Part 2: Practice Routines for the Learner (The Improvement Kata)

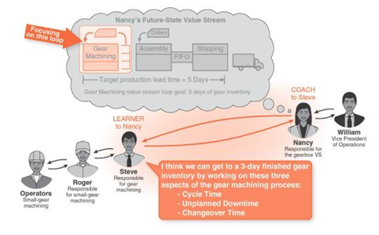

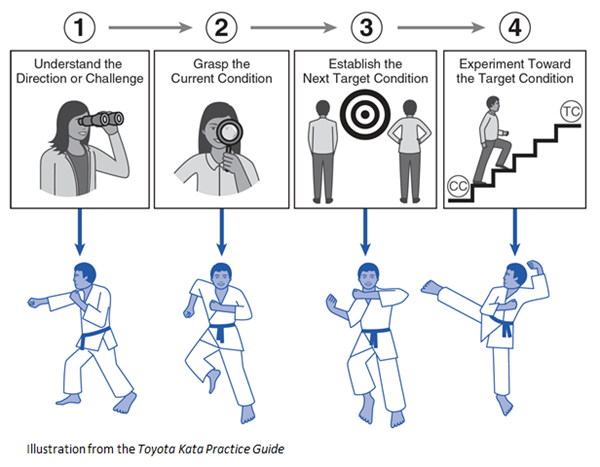

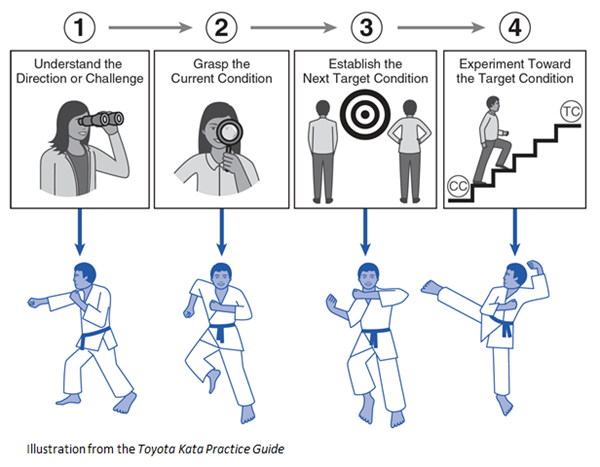

At a high level the “Improvement Kata” is expressed as a four step process that maps to pretty much any process of learning, discovery or problem solving that works.

In this section, there is a chapter for each of the steps above that sets out, in detail:

- The higher level purpose of the step – the “why?”

- The discrete steps you should practice, including detailed “How to” instructions as step-by-step Starter Kata that a learner should follow precisely while he is grounding on the basics.

I believe it is equally important for new coaches to work hard to keep their learners focused on the Starter Kata as well – you are both in learning mode. (More about coaches in the next section.)

I do, though, want to discuss the one step where I can see people having the biggest struggle mapping the explicit Starter Kata to their own situation: Grasp the current condition.

The Starter Kata steps for Grasping the Current Condition are explicit and detailed. At a high level they are:

1. Graph the Process Outcome Performance

2. Calculate the Customer Demand Rate and Planned Cycle Time

3. Study the Process’s Operating Patterns

4. Check Equipment Capacity

5. Calculate the Core Work Content

The book devotes several pages to how to carry out each of these steps. However, the examples given in the book, and the way it is usually taught, use the context of industrial production processes. This makes sense. Industry is (1) the origin of the entire body of thought and (2) the world the vast majority of practitioners live in.

But we legitimately get push-back from people who live in a world outside of industry. What I have found, though, is when we work hard to figure it out, we can usually find solid analogies where the Starter Kata do apply to practically any non-industrial process where people are trying to get something done.

Often the mapping isn’t obvious because people in non-linear work are less aware of the repeating patterns they have. Or they live in worlds where the disruptions are continuous, and though a cadence is intended, it seems to be impossible to achieve. However, if you are legitimately making an effort, and having trouble figuring out how to apply the Starter Kata outlined in the book to your own experience, here is an offer: Get in touch. Let’s talk and see if we can figure it out together.

A Little More about Starter Kata

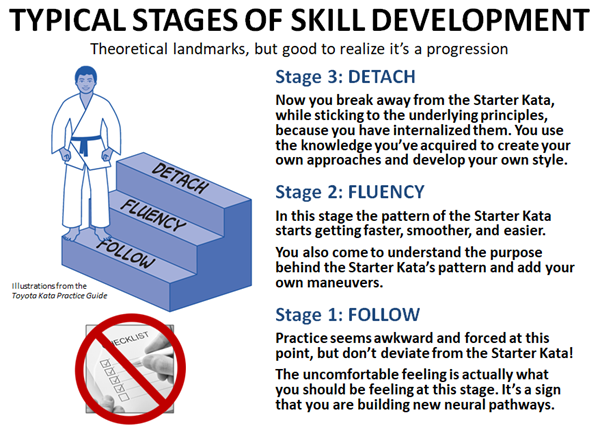

The concept of “Starter Kata” is new since the publication of the original book. Actually it isn’t really new, just much more explicit now.

When we see working examples, such as in books about A3 Problem Solving, we are often looking at the work of people who are unconsciously competent, if not masters, of doing this.

To someone trying to learn it, though, all of these “different approaches” can be confusing if they are trying to just understand what they should do. A coach trying to help by giving them a lot of general guidelines as decision criteria often isn’t helping much to clarify the confusion. (And may well be adding to the frustration.)

The point of a “Starter Kata” is to provide a high level of structure that can guide the learner until she “gets” the higher level purpose. In traditional east-Asian martial arts, this higher purpose is often left unspoken, with the intent that the learner will reflect and come to deeper understanding.*

In the Practice Guide Mike is much more clear about the underlying “why” of the emphasis on initial rote practice. We, the readers, are in Stage 1 in this illustration:

If you are trying to understand what Toyota Kata is about, or you are trying to up your own skills for process improvement or problem solving, then read the steps that are set out in the book and follow them exactly as they are written to the best of your ability. Do this even (especially!) if they don’t seem 100% appropriate to the problem you are trying to solve.

“But I’m not a beginner” you might say.

Let me issue this personal challenge: Pretend you are a beginner. All of us can learn from going back and applying the basics. You may well discover:

- Additional insights about things you are already doing. (Which I did.)

- Some approaches that are simpler and more effective than what you have evolved over the years. (Which I did.)

- More comfort with using these Starter Kata as a teaching guide for others. (Which I have.)

Although this material on the Improvement Kata has been “out in the wild” for some time, I think I can honestly say that The Toyota Kata Practice Guide is a vastly better expression than I have seen anywhere else – including earlier material from Mike Rother – and my own previous material for that matter. (I started making changes to my own materials based on my early look at the manuscript.)

Part 3: Practice Routines for the Coach (The Coaching Kata)

This is the new and exciting part.

While there has been a fair amount about the Improvement Kata out there for a while, the only things we have had about coaching have been the “5 Questions,” a few YouTube videos and some general principles. I’ve tried on this site to relate my own experiences as I learned, but The Toyota Kata Practice Guide is, in my view, the first truly comprehensive reference that wraps up everything we knew up to this point in a single reference.

Tangent: Learn to Play Before You Coach

Though this is part of the message in the book, what follows are my own experiences and interpretations.

Nearly all managers want to jump right into coaching. They see the “5 Questions” and some of them think that is all there is to it – just ask those questions and we’re good. Actually, that’s kind of OK so long as you realize that you are probably making mistakes, and are consciously and deliberately reflecting on what those mistakes might be. But that reflection is often what doesn’t happen – people tend to presume competence, and don’t challenge their own role if they see learners struggling. It is a lot easier for me to blame the learner, or to say “this kata thing doesn’t work” than it is to question my own competence.

Until you have struggled as a learner to apply the Improvement Kata (using the Starter Kata) on a real problem (not just a classroom exercise) that affects the work of real people and the outcomes to real customers, please don’t just pick up the 5 Questions card and think you are a coach.

Coaching Starter Kata

If you truly understand the Improvement Kata, and then go to a Toyota, or other company that has a solid practice for continuous improvement, you will readily see the underlying patterns for problem solving and improvement. Coaching, though, is a bit more abstract – harder to pin down into discrete steps.

Read John Shook’s excellent book Managing to Learn (and I highly recommended it as a complement to The Toyota Kata Practice Guide), and you will get a good feel for the Toyota-style coaching dialog. You won’t read “the 5 Questions” in that book, nor will you see the repetitive nature of the coaching cycles that are the signature hallmark of Toyota Kata.

Here’s why:

There are a couple of ways to learn that master-level coaching. One is to work your entire career in an organization that inherently thinks and talks this way. If you do, you will pick it up naturally “as the way we do things” and won’t give it another thought. Human beings are good at that – its social integration into a group.

Imagine, if you would, growing up in a community where everyone was a musician. Thinking in the structure of music would be innate, you wouldn’t even be aware you were doing it. Growing up, you would learn to play instruments, to sing, to compose, to arrange music because that is what everyone around you was doing. That is also how we learn the nuance of language. We can see throughout history how mastery in arts tends to run in families. This is why.

And that is how the coaching character in Managing to Learn gained his skill.

But if you want to learn music, or another language, or some other skill, when you aren’t immersed in it all day, then you have to learn it differently. You have to deliberately practice, and ideally practice with the guidance of someone who not only has the skill you are trying to learn but also has the skill to teach others. (Which is different.)

The question Mike Rother was trying to answer with his original research was “How can the rest of us learn to think and coach like that?” – when we don’t live in that environment every day. In those cases we have to be overt and deliberate.

The real contribution that Mike has made to this community is to turn “coaching” from a “you know it when you see it” innate skill into a routine we can practice to learn how to do it. I can’t emphasize that enough.

And, although the Coaching Kata is taught within a specific domain of process improvement, the underlying questions are the basis for anything people are working to achieve. Cognitive Based Therapy, for example, is structured exactly the same way.**

OK – with all of those rambling thoughts aside, let’s dig back into the book.

As in the previous section, we begin with an introduction section that gives an overview of what coaching is actually all about.

Then the following chapters successively break down the coaching cycle into finer and finer detail.

Coaching Cycles: Concept Overview

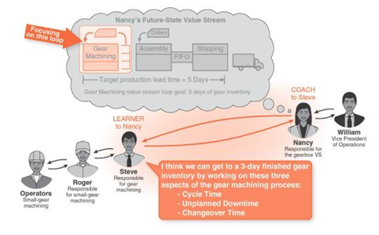

This chapter emphasizes the cadence of coaching cycles, the importance of frequent practice (for both the coach and the learner), and the purpose and structure of the “5 Questions.”

A key point that bears emphasizing here is that the purpose of coaching is to advance the learner’s knowledge, both of the process being addressed and the “art of scientific thinking.” Thus, the reason the coach asks the questions is to learn where the boundary is between what the learner knows, and what the learner doesn’t know.

Often the learner himself isn’t aware of that boundary. Again, it is human nature to fill in the narrative, complete the story, and create meaning – jump to conclusions even with limited evidence. By asking for specifics, and by gently asking for evidence – “How do you know?” types of questions, the coach learns that point where the learner moves beyond objective facts and into speculating. (Or, ideally, says “I don’t understand” or “I don’t know” about something that needs to be understood or known.) The “next step or experiment” should be a step that pushes that threshold of knowledge boundary out a little further.

In the book, we get an example coaching dialog, and some warnings and cautions about commonly ingrained habits we probably all have to “give the answers” rather than “ask the questions.”

This chapter wraps up with some advice about when (and why) you (as a coach) might need to let go of the formal structure if a learner is struggling with it.

How To Do a Coaching Cycle: Practice Routines

After the overview, Mike gets down to what to do, how do give good corrective feedback, and keep the learner in the game psychologically.

He then gives us a detailed example coaching dialog, and afterwards, puts us into the role of the 2nd Coach, challenging the reader to predict what feedback the 2nd coach should give before reading what actually happens.

The dialog is followed by what I think is the most powerful part of the book as he guides us through each of the “5 Questions.” For each one, we get a description of why that question is important, its purpose, followed by:

- Key Points – Advice that reflects feedback and helpful tips gained over the years from the entire community.

- Clarifying Questions – Possible follow-on questions that can help the coach clarify what the learner is intending and thinking.

- Potential Weak Points – Things to specifically look for that can help the learner construct better logical connections and experiments.

This chapter, in my view, is alone worth the price of the book. Everything else is bonus material.

Conclusion

This post took me quite a bit longer to write than I predicted it would, and I’ll judge that it is still rougher than I would like. But I am going to suppress my inner perfectionist and put it out there.

Anyone who knows me is aware that, even before it was published, I have made no secret about touting this book to anyone who is interested in continuous improvement.

In the end, though, this book is asking you to actually do some work. People who are looking for easy answers aren’t going to find them here. But then, I really don’t think easy answers can be found anywhere if we are honest with ourselves.

As I said about the original book back in 2010, I would really like to find copies of The Toyota Kata Practice Guide on the desk of every line leader I encounter. I want to see the books with sticky notes all over them, annotated, highlighted. The likely reality is that the primary readers will be the tens of thousands of staff practitioners who make up the bulk of the people who are reading this (you aren’t alone).

If you are one of those practitioners, YOUR challenge is to learn to teach by the methods outlined here, and then learn to apply them as you coach upward and laterally to the leaders of your respective organizations. Those conversations may have different words, but the basis is still the same: to help leaders break down the challenges they face into manageable chunks and tackle the problems and obstacles one-by-one.

One Final Note:

The overall theme for the 2018 KataCon is practice – keying off of the release of this book. Come join us, share your experiences, and meet Mike Rother, Rich Sheridan, and other leaders in this awesome community.

——–

*Those of us who were taught by Japanese sensei, such as Shingijutsu (especially the first generation such as Iwata, Nakao, Niwa) were expected to follow their instructions (“Don’t ask Why?… Say “Hai!”). It was implied, but never stated, that we should reflect on the higher-level meaning. Over the years, I have seen a fair number of practitioners get better and better at knowing what instructions would be appropriate in a specific case, but never really understand the higher-level meanings or purpose behind those tools. Thus, they end up as competent, but mechanistic, practitioners.

**Note: Mastering the Coaching Kata will not make you a therapist, though it may help you empathetically help a friend in need.