“Our challenge is to improve our patient satisfaction scores.”

This seems to be a fairly common theme as I continue to work in the health care arena.

Background

In the U.S. at least, most major health care operations use one of a couple of major service providers (such as Press Ganey) to survey their patients, and report aggregated patient satisfaction scores to them. Those scores provide a percentile rank of how that facility stacks up against others across various categories. The scores are also made public, and often influence public funding decisions within a region. Thus, they are a big deal.

Chasing the Patient Satisfaction Numbers Doesn’t Work

Here’s the problem. More than a few times I have seen an improver working on a challenge to improve these patient satisfaction numbers. It might be something like “Achieve a 70th percentile score on ___.) with a specific score that has to do with their area.

So far, that’s not a real problem. But what happens next might be.

It is very common to focus solely on the end result, without a lot of thought into the underlying things that drive that result.

Specifically, I have seen more than a couple of cases where a manager is working to directly influence how a patient (customer) will answer the questions on the survey. They parse the question, and try to determine what this word, or that word, actually means to “the patient.” The worst case was trying to introduce fairly heavy handed scripting… “Is there anything I can do for you to be more comfortable?” into every patient interaction.

I certainly can’t speak for the population of patients, but I can say that when I pick up on a scripted phrase, I become very aware of what it is, and it leaves a disingenuous taste.

It’s About the Patient Experience

The patients’ experience is what drives how (and even if) they will answer the questions on these surveys. If their experience was overall favorable, they will be biased to give favorable replies. The opposite is even more true. One bad experience will negatively bias all of their answers.

Here’s the question I ask that sometimes stumps people:

What experience to you want the patient to have?

(If you aren’t in health care, substitute the word “customer” for “patient.”)

If your scores on “Were the staff concerned for my comfort?” are low, think about what experience would give the patient confidence that staff were concerned. Being continuously asked about it with a rote phrase probably isn’t going to do it. But leaving them parked in the hallways with no interaction might be (for example), something that creates discomfort. (“Comfort” has a psychological, as well as a physical component.) People will put up with a lot of discomfort if they know the higher purpose. It’s hard to make the case for parking the patient in the hallway. That just says “I don’t have anywhere to take you.”

So think deliberately. If everything the patient experienced were something you were doing on purpose, because it contributed to the experience you want the patient to have, what would that look like?

Don’t worry right now about whether that is hard or not. Let go of your internal issues for a while. Just sketch out that awesome “insanely great” patient experience. You don’t have to think of every detail. What are the attributes? What is the flow, from the patient’s perspective – the sequence of events they will experience.

For example, construct a story, told from the patient’s point of view, of coming in for outpatient surgery.

What happens from the time they have their initial consultation until they are on their way home. (And what happens after they get home?) Again, don’t worry about “we can’t do that because…” stuff, we’ll deal with that later.

What experience, what story, would leave the patient with the impression that you are working as a team, that you know what you are doing, that there is a competent process at work to provide safe, effective care and actually care about their experience?

Don’t forget to include your administrative communications in this process – what phone calls do they get? What paperwork do they get? What does crystal-clear billing look like?

Build a block diagram, a story board, of the patients’ ideal flow through the system.

What would a wait-free, smooth flowing experience look like?

Learning From Disney

In Disney theme parks, they make a clear distinction between “On Stage” and “Off Stage.” Their employees (all of them) are referred to as “Cast Members.” Anytime a Cast Member is visible to guests, they are “On Stage.” They are performing. They are part of creating the story, the experience, they want the guest to have.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, in the tunnels, off stage, are the processes required to create the “On Stage” performance. It’s a show.

The guest experience is designed. Once it is designed, it is created by the process.

Disney’s priorities (in order) are:

- Safety

- Courtesy

- Show

- Efficiency

Translated, they place putting an a good performance above being efficient. But if pushed, a cast member may break character if required to be courteous. And they will get snippy with someone who persists in doing something unsafe in spite of courteous requests.

What on Earth does this have to do with health care?

Everything. That is if you are trying to create a safe, professional and competent impression to your patients.

What is the Actual Patient Experience?

Now we have a sense of the ideal, it’s time to understand what is really happening. Again, start with the patient’s experience.

What happens at each interaction? What questions are asked? Who asks them? How often are they moved? Where and when are they waiting, and why?

Use “typical” rather than exceptional cases here. One thing I am seeing is, yes, every case is different but in reality, most are handled within a routine.

Pay attention to the “on stage” part of your process. This is what the patient sees, and what creates their experience.

At the same time, look at the behind-the-scenes “off stage” flow to see what might be causing a less-than-ideal patient flow. For example – The patient’s experience is that he is alone in an exam room waiting, reading Time Magazine for 20 minutes. That is the “on stage” part.

Meanwhile, “back stage” you have a nurse on the phone trying to get the results of tests that were done by another provider. (This is a real-life example.)* (There was also a physician waiting on them!)

Your Processes Create the Patient Experience

(Again, substitute “customer” for “patient” and this becomes an essay for everyone.)

Your Patient Satisfaction scores are driven by the patients’ experience.

The patients’ experience is established by your “on-stage” (patient facing) process.

Your “on-stage” process is the result of your “off-stage” execution.

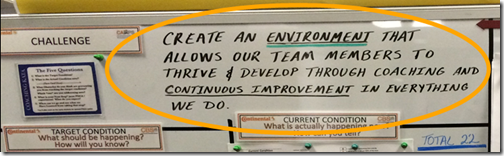

The people making the improvements need to be challenged, and focused on, creating a specific experience for the patient.

Linking to Policy Deployment

All of that begs the question: Who should make the linkage between process performance and patient satisfaction, because those scores do matter, in a very big way.

Let’s look at this from a policy deployment standpoint.

Certainly Administration (the executives) should be tracking their scores. From their perspective, these are an important (along with patient safety, quality, length-of-stay, financial performance, etc) aspects of how the organization is performing.

They see the overall performance and trends. And they can see how each department is performing.

But the patient’s experience is cross-functional. The patient only sees “the hospital.” He doesn’t see, and doesn’t care, that Admissions, the lab, the Emergency Department, Outpatient Surgery, Environmental Services (who cleans his room) and Radiology are all different departments. The patient doesn’t see, and doesn’t care, that “the clinic” and “the hospital” are separate legal entities.

As part of Policy Deployment, Administration should be establishing operational standards and challenging the Department Directors to meet them. Those standards are based on what Administration believes will move the needle on the patient satisfaction scores. In reality, this is also an experiment. Does this operational standard meet our customer’s expectations?

They also are making sure the Directors are working on the cross-functional interfaces between their departments. (If it isn’t the Directors’ job to do this, whose job is it?)

Key Point: Until you are consistently delivering the product or service, there is little point in trying to change things up. Set a standard, strive to meet it. Once things are somewhat stable, then you can evaluate whether your standard is adequate or not. Think about it… what is the alternative? You have random execution that is randomly working. You don’t know why. You can’t talk to people about performance until they can demonstrate consistent execution.

Summary

Your patient satisfaction scores reflect the experience of the patient.

The patient experience is the outcome of your on stage process performance.

Your on stage process performance is ultimately driven by your back stage process execution.

If you want to improve your patient satisfaction scores, establish the operational standard you want to strive for that you think will improve patient satisfaction.

Then strive to develop a process that meets that operational standard.

THEN you can evaluate whether your process is adequate.

_________

*This was an obstacle in front of a target condition focusing on hitting a standard for “In, Seen and Out” within a specific time frame for routine pre-procedure consultations. They fixed it. Patients no longer have to sit and wait while someone hunts down those test results.

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a

Sometimes people fall into a trap of believing they understand a process if they can successfully predict it’s outcome. We see this in meetings. A problem or performance gap will be discussed, and an action item will be assigned to implement a solution.

Sometimes people fall into a trap of believing they understand a process if they can successfully predict it’s outcome. We see this in meetings. A problem or performance gap will be discussed, and an action item will be assigned to implement a solution.