This is the first in series of posts I am drafting about what I saw, heard, learned at KataCon6 in Austin.

I was originally writing this up in huge chunks, maybe two posts. But when I bounced the “Part 1” draft off Craig Stritar, I got some good advice – there are a lot of topics here, and it might be more useful to break these up into smaller pieces, so that is what I am doing.

My intent is to generate discussion – so I would like to explicitly invite comments, questions and especially take-aways from others. In other words – let’s continue the great conversations that were taking place in Austin.

Day -1 and Day 0

Lean Frontiers traditionally runs the TWI Summit and KataCon back-to-back in the same week, alternating which comes first. This year the TWI Summit was Monday and Tuesday, and KataCon was officially Thursday and Friday.

Both conferences, though, have semi-formal activities and get-togethers prior to the first official day. Since there are things going on Wednesday, some people begin to arrive Tuesday evening. And because I was already on site from the TWI Summit, Tuesday evening is really when things got started for me.

Something I have observed in the past is that each KataCon seems to take on an informal theme of its own – a common thread or feeling that is established more by the participants than the presenters. Where the first KataCon was the excited buzz of a community coming together for the first time, this one seemed to me to be like a reunion. To be clear – it was a welcoming reunion. Unlike other conferences I have attended, there is nothing “clique-ish” about this one.

With that reunion theme, I want to give a shout out to Beth Carrington. She is a vital member in the fabric of this community and this is the first KataCon she has missed. I think I can speak for all of the regulars when I say “we missed you.” Those who do not know you still felt your presence and influence through your impact on the rest of us.

The other thing (for me) that was cool was just how much of the conversation took place after hours in the hotel lobby bar. There were long-time regulars catching up, and there were first-timers and newbies getting rich tutorials and insights from the veterans. That is why I titled this section starting with day “-1.” Those conversations were happening on Tuesday afternoon and evening as people started to arrive.

This is a community of sharing. Many of us are consultants and nominally competitors in an increasingly crowded market. Yet nothing was held back. We build on each other’s stuff, and pretty much everyone shares what they are thinking with everyone else. That’s pretty cool in my estimation.

The Kata Geek Meetup

The Kata Geek Meetup started at the first KataCon. At the time it was an informal mailing list invitation to attend a get-together before the conference started. Everyone got a “Kata Geek” button to wear with the idea that the other conference participants could identify those with a bit more experience under their belt if they wanted to ask questions, etc. The event wasn’t publicized on the conference agenda.

Over the years this has morphed into a mini-preconference that is open to all who can attend. People share brief presentations – maybe something they want to try out for an audience, maybe a rhetorical question, maybe a “what we are learning.” The pacing is much more flexible than the actual conference, and there is time for lively discussion and Q&A. Sometimes tough, challenging questions get asked – though always in the spirit of curiosity rather than trying to one-up anyone.

As I get into the actual content, I want to clarify my purpose in writing what I do. When I listen to presentations, I am more likely to take down notes of what thoughts or insights I take away than the actual content. These things are often a fusion of key points the presenter is making, or the way they are saying something, and my own paradigms and listening framework. That is what I am writing about here. I am not making any attempt to “cover” the presentations as a reporter or reviewer would or be complete in mentioning everything that was said.

PLEASE contribute in comments if something I didn’t mention resonated with you, or something written here sparked another thought for you.

Dorsey Sherman made a simple point: All coaching is not the same. It depends on your intention (as a coach).

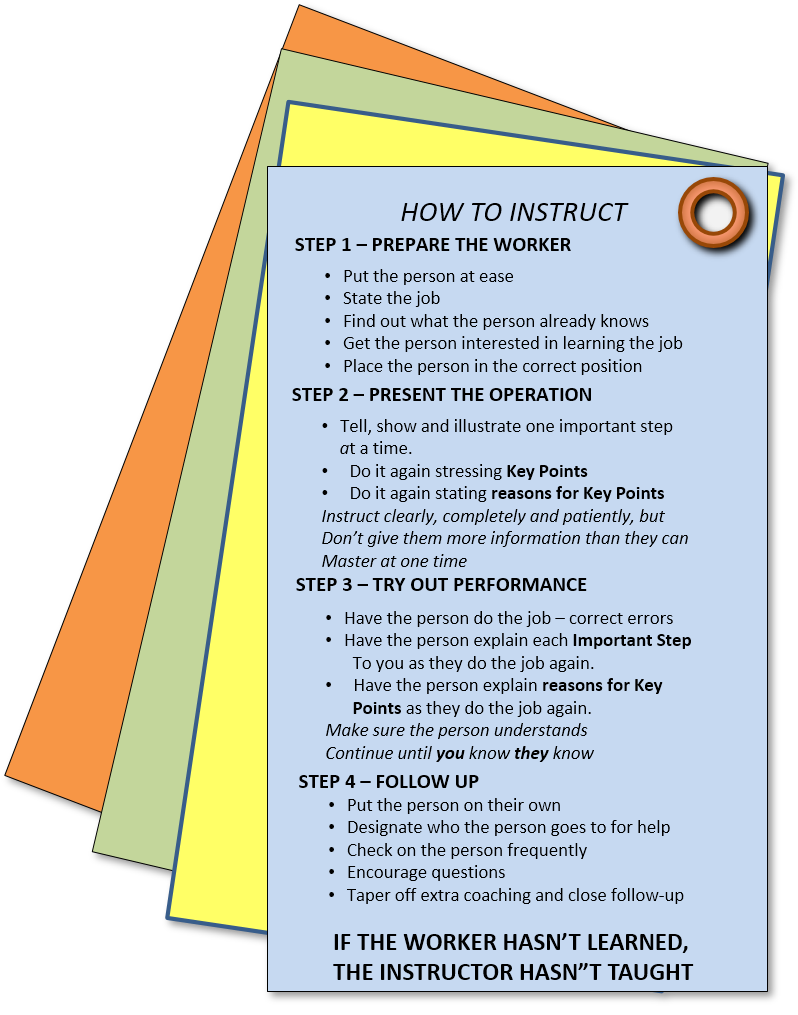

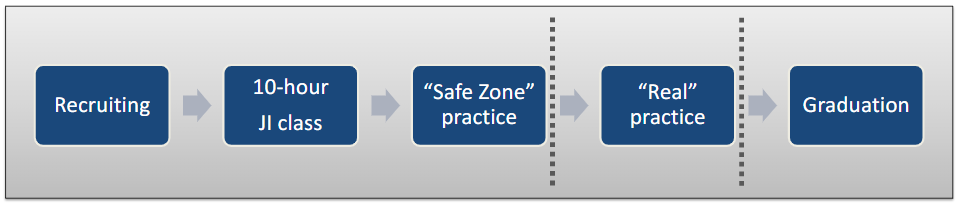

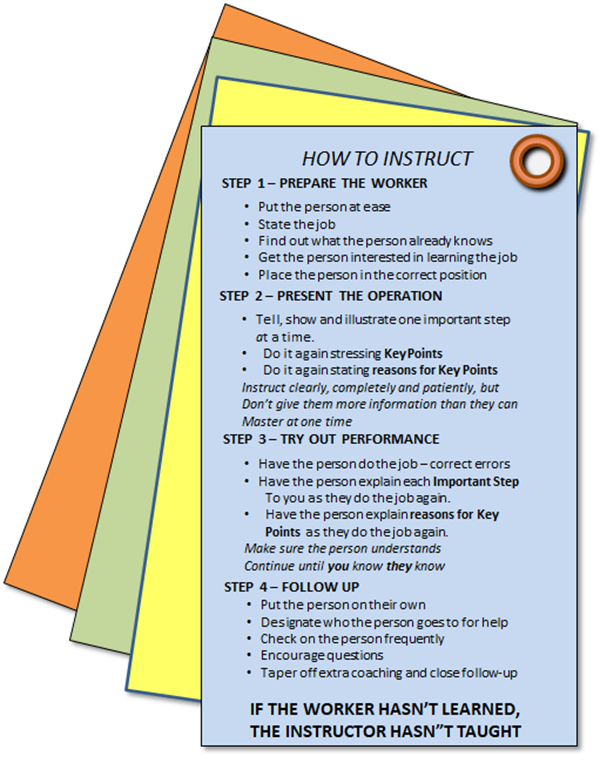

Thinking about it a bit, the classic TWI Job Relations is coaching – usually (in its original form) to fix or change behavior in some way. TWI Job Instruction is coaching – in this case to teach / coach for skill. At a deeper level, the classes themselves are designed to give novice coaches a structure they can practice.

The Improvement Kata framework itself is a pretty universal structure that I can pour a lot of different intentions into and test ideas that I think will move me in a particular direction. I think all coaching is a process of exploring and experimentation simply for the fact that we are dealing with other people. We may begin with assumptions about what they think, know, feel but if we don’t take deliberate steps to test those assumptions we are just guessing in the dark.

Hugh Alley

Hugh is a friend from neighboring beautiful British Columbia. I recall telling an audience in British Columbia that Canada represents that nice couple living quietly in an apartment over a rowdy biker bar. 😉

A couple of take-aways I noted down as Hugh was speaking:

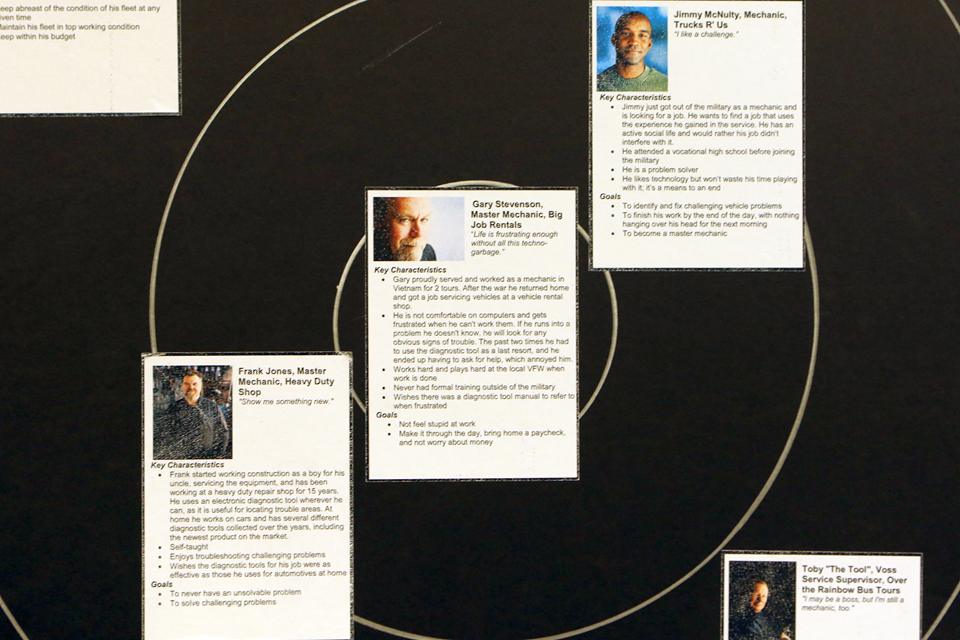

- The storyboard represents a picture of the learner’s mindset – it is like an MRI.

- Correction: Hugh informs me (see his comment below) that the MRI analogy came from Panos Eftsa.

I loved that analogy. When I look at the storyboard I am really seeing how organized the learner’s thinking is, how detailed, and whether or not they are connecting the dots of cause and effect from the levels of their target conditions to their metrics down to their experiments and predictions.

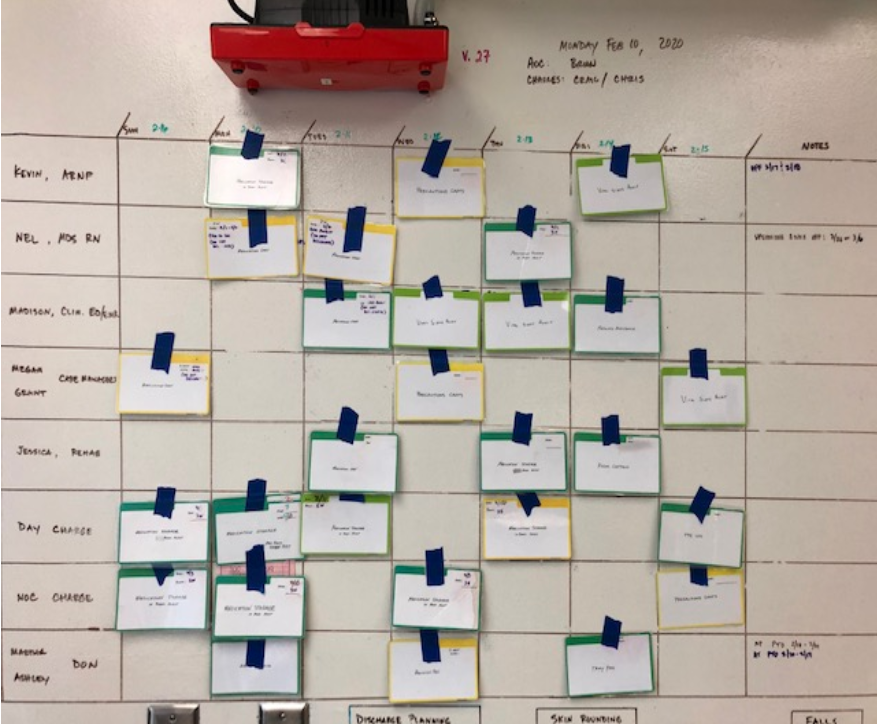

I thought of an image like this:

Hugh was asking the audience about his situation of a client company that started up 13 storyboards at once. Some of the thoughts that came out:

- Um… OK, you have already done that. *smile*

- Establish a specific area of work for each board, each coach. Don’t try to bring them along all at once.

- Work through each phase of the Coaching Kata, anchor success and mastery one-by-one rather than trying to batch everything through at once.

What was good about his client’s approach, though, is they are establishing a routine of people talking about why the work is the way it is – and that is awesome.

Toyota Kata Level-Set

At this point I am letting go of trying to write in the sequence of the agenda. There are topics I want to go deeper into, others I may combine.

Oscar Roche

The Toyota Kata Summit attracts people across a wide spectrum of knowledge and experience with “Toyota Kata” itself. Balancing the conference can present a real challenge. There are people who have been practicing this in the trenches for a decade and are pushing the boundaries. There are people who might have read the book and are curious about learning more.

One of the countermeasures is a “level set” presentation at the beginning of the formal conference. This is a brief overview of the fundamental principles of Toyota Kata and I think it is a good grounding for the veterans as well – it is always good to pull us back to the basics now and again.

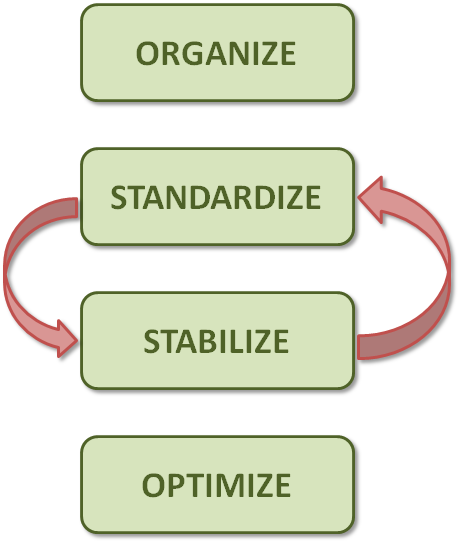

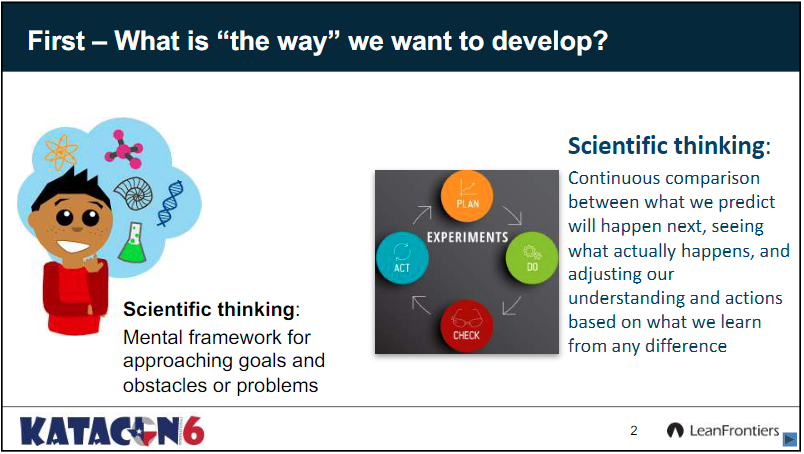

Traditionally Mike Rother has done the “level set” presentation. This year, though, was a change and Oscar Roche stepped up. Oscar’s title slide drove home a critical point that we often miss:

- “Kata is

thea thing that helps you developthea way”

His next slide answers the implied question:

My thoughts – and a digression

A lot of practitioners get hung up on the idea that the way they know best is the best way, sometimes to the point of believing it is the only way. This is true for Toyota Kata practitioners, general “lean” practitioners, Six Sigmites, Theory of Constraints, TQM, you name it.

Sometimes I hear people make sweeping statements that dismiss an entire community, perhaps focusing in on one thing they perceive as flawed. “Lean addresses waste but not quality (or not variation).” “TOC doesn’t address flow.” “Six Sigma is only about big projects.” “Toyota Kata is only about the storyboard.” All of these statements are demonstrably false, but it is hard to have an open minded discussion that begins with an absolute.

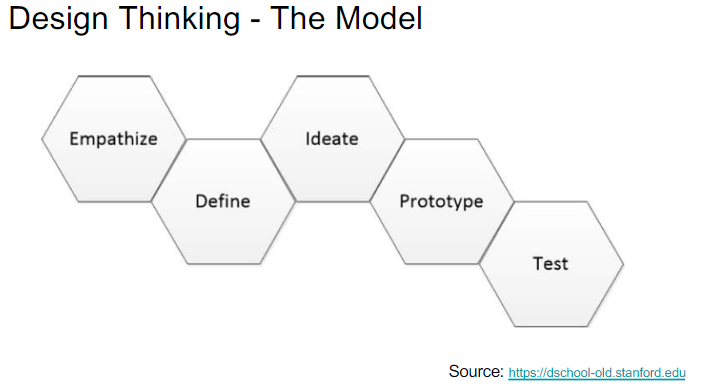

All (credible) continuous improvement has a foundation of scientific thinking. Any approach you take has some basic “first moves” to get you started thinking that way. Toyota Kata is more explicit about that than most, but the underlying principles are the same across the board.

Oscar’s opening slide emphasized this point: Toyota Kata is a way, not the way. We can all learn to adapt vs. continuing to hammer on a nail that has hit a knot and is bending over.

Steven Kane

- A teacher provides insight.

- A coach pulls insight from the learner.

- You may go back and forth between these two roles. Be crystal clear which role you are in at the moment.

I’ll probably write more about this in the future in a separate post. What I liked about this thought is that it is appropriate for the coach to provide direction or insight at times. My own presentation at KataCon kind of hinted at this – someone has to bring in the paradigm of what “really good” looks like.

Nevertheless, it is critical for the coach to drop into the “teacher” role only when necessary (which I think is a lot less often than we like to think it is), and then get back into true “coach” mode as quickly as possible. Why? Because unless I am in “curious” mode with my learner, I really have no way to know if my brilliant insights got any traction. 😉

Paraphrasing from Steven’s presentation, the question “What did you learn?” is there to see if there has been a moment of discovery.

- The Power of Nothing

The most powerful follow-on question to “What did you learn?” is silence. If initial response is fluffy or vague, or you think there is more, just wait. Don’t try to say anything. The learner will instinctively fill in the awkward silence.

- Target Condition vs. a Result

This came up a lot during the conference. Billy Taylor talked about the difference between “Key Activities” (KA) vs. “Key Indicators” (KI or KPI). What are the things that people have to do that will give us the result we are striving for? Leaders, all too often, push only on the outcome, and don’t ask whether the key activities are actually being carried out – or worse, don’t think about what activities are required (or the time and resources that will be required). I’m going dedicate a post on that topic.

And finally (and I am making this one bold so I remember it!) –

- Don’t rob the leaner of their opportunity to make discoveries.

How often do we do that?

Michael Lombard

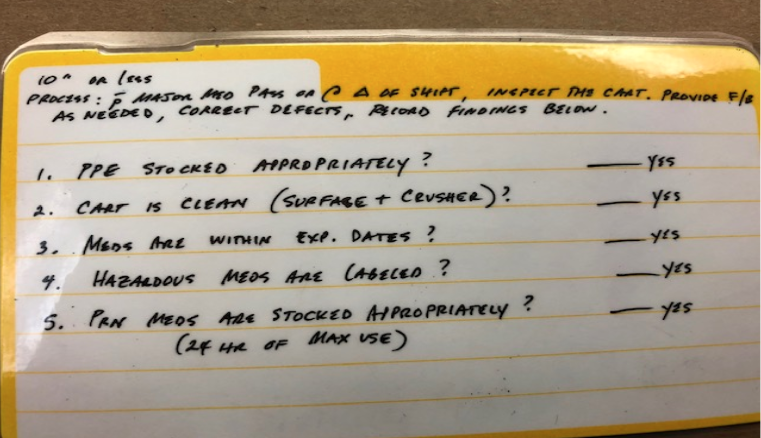

Michael had a brief presentation on “What we are learning” focused specifically into the health care field. His thoughts on medical students actually apply universally with anyone who perceives themselves as successful.

- We need to de-stigmatize struggle. Productive struggle is part of deep learning. Medical students should not feel shame when they struggle to learn a new skill.

Why do they? Michael pointed out that the people who manage to get admitted to medical school are high-achievers. Things may well have come easily for them in high school and their undergraduate studies. Now they are in a group with other high-achievers, they don’t stand out from the crowd, and the concepts can be difficult to master.

We see the same things in other environments – a lot of people in senior positions of authority got there the same way. Many are ultra-competitive. Now we are asking them to master a skill that runs entirely counter to their paradigm of intuitive decision making. Note that that intuitive decision making has worked well for them in the past. But maybe they are at the limit of what they can do themselves, and have to find ways to engage others. I don’t know… there could be lots of scenarios that put them into completely unfamiliar territory.

Our challenge is how we de-stigmatize struggle.

Michael’s other key point touched one of the Wicked Problems in health care. I’m going to go into some more depth when I get to Tyson Ortiz’s presentation, but want to acknowledge the Great Question posed here:

- “99% of activity needed to maintain wellness never involves a health system. Can we increase the striving capabilities and mental resilience of our patients, families, & communities so they can own their health journey?”

Amy Mervack

Amy tied our practice to the concept of “mindfulness.” One of her key points was learning to see that the pattern we are trying to teach may well be there in some form other than the explicit Improvement Kata.

She wrapped up with some guided practice of “being mindful” for the audience – which she said stretched her a bit as she had never done it with a group that large.

As a change agent, a mindfulness approach is critical. We have to learn to find everything about the way things are being done that we can leverage and extend. This means paying attention vs. the mindless approach of dismissing them out of hand with a single statement. Making people feel wrong may get attention focused on you, but it rarely helps make progress.

Experientials

The afternoon was “Experientials” – four hour breakout sessions that went deep into a particular topic. As Craig Stritar and I were hosting one, I didn’t attend any of the others. Always a downside of being up-front – I see more of my own stuff than the awesome things others bring.

As I mentioned above, I am going to be digging into some of the topics in more depth, and I want to keep those individual posts focused vs. trying to cover a rich diversity of discussions all at once. Hmmm… one-by-one vs. batching. That might be a concept. 😉