“No… this is coaching. That means I talk, you listen.”

Many years ago, those words began a 20 minute session that I can best describe as an “a** chewing.” The boss systematically went through all of the little notes he had been saving for over a year – like the fact that someone had commented that I had a cow lick in my hair one day many months ago, which was framed as “lack of grooming.” None of this, of course, had anything to do with what had triggered the tirade. As I recall I had scheduled a meeting with a supplier over something that he had thought was more important. Needless to say, the guy didn’t have a lot of credibility with the group, as this was pretty normal behavior.

What Is Coaching?

While my (real life!) example may have been a somewhat extreme case, a recent HBR article by Julia Milner and Trenton Milner titled Managers Think They’re Good at Coaching. They’re Not offers up some preliminary research that supports the hypothesis in their title.

What they found was that what most managers described as “coaching” was, in fact, offering direction couched in the form of advice.

As an alternative, they offer up a definition of coaching by Sir John Whitmore:

“unlocking a person’s potential to maximize their own performance. It is helping them to learn rather than teaching them.”

I can see where it would be easy to argue about whether or not “teaching them” is actually different from “helping them learn” but I tend (these days) to come down on the side of seeing a big difference.

To quote from David Marquet:

“… they have to discover the answers. Otherwise, you’re always the answer man. You can never go home and eat dinner.”

And, indeed, I see the effect of managers trying to always be “the answer man” every day – even this week as I am writing this.

Milner and Milner conclude with this take-away:

coaching is a skill that needs to be learned and honed over time.

This, of course, is consistent with the message that we Kata Geeks are sending with Mike Rother’s Coaching Kata.

The challenge for these managers is the same as that posed by Amy Edmonson in a previous post, It’s Hard to Learn if you Already Know.

Learning to Coach

The HBR article lists nine skills that the authors associate with coaching:

- listening

- questioning

- giving feedback

- assisting with goal setting

- showing empathy

- letting the coachee arrive at their own solution

- recognizing and pointing out strengths

- providing structure

- encouraging a solution-focused approach

Unfortunately just memorizing this list really isn’t going to help much, because there are effective ways to do these things; and there are ways that seem effective but, in reality, are not.

The question I would like to examine here is how practicing the Coaching Kata might help build these skills in an effective way.

I’m going to start with the second from the last: Providing structure.

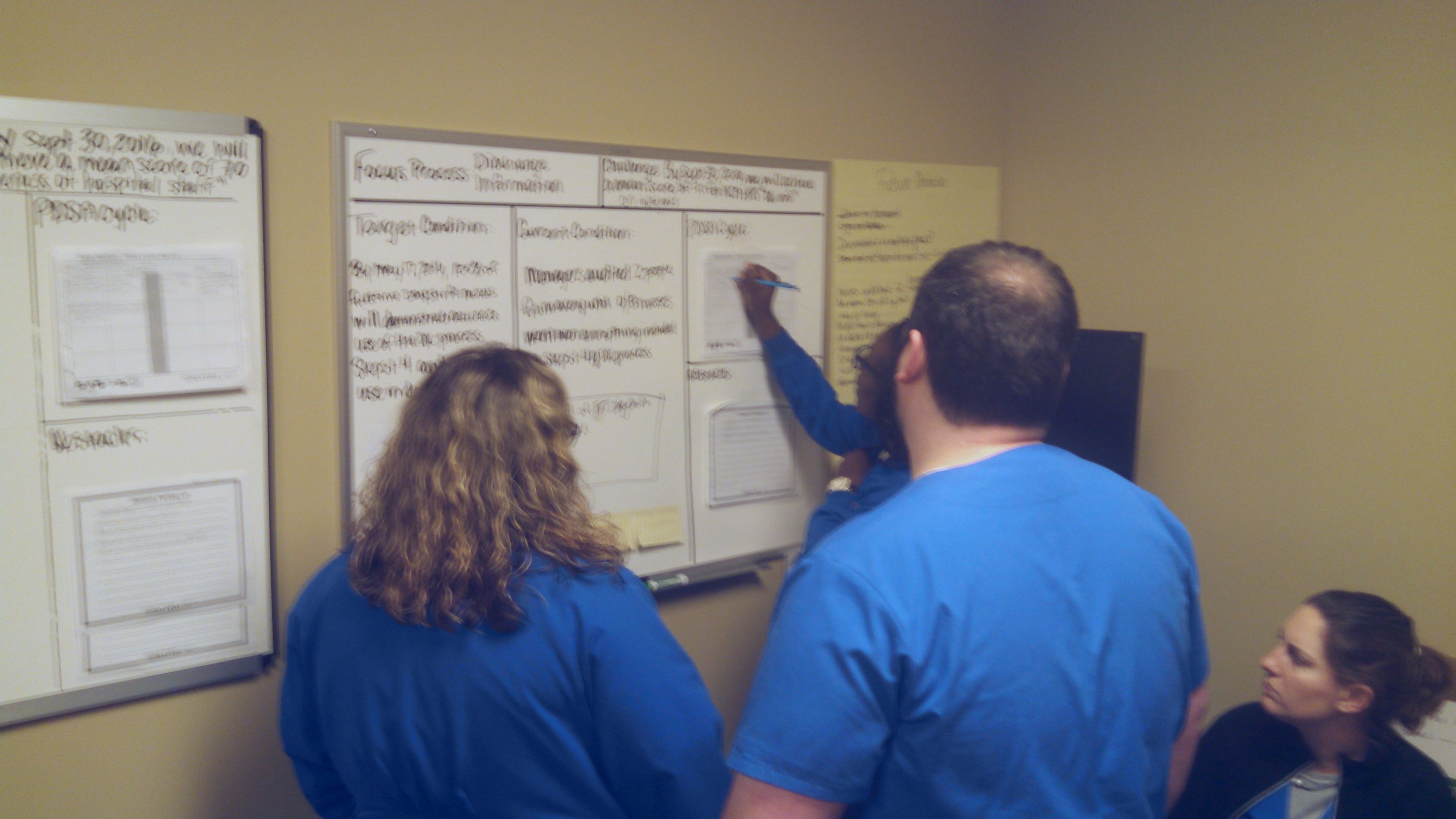

The very definition of kata implies a structure. Especially for that critical early practice, the Coaching Kata and Improvement Kata provide a mutually supporting structure for both the Coach and the Learner to practice building their skills. The Starter Kata that Mike Rother describes make up the most rigid form of that structure with very specific activities designed to push problem solving and coaching skills.

As the organization matures, of course, that structure can shift. But even very mature organizations tend to have “the way we do things” which provides a safe structure that people can practice and experiment in. Ironically, this is the very purpose of standardization in the Toyota sense. (This is very different from what most organizations think of as “standards” – where experimentation is forbidden! )Without this baseline structure, sound experimentation is much more difficult.

Continuing to skip around on the list, let’s look at assisting with goal setting.

The very first step of the Improvement Kata is Understand the Challenge or Direction. Right at the start, the coach must assist the learner with developing this understanding. At the third step we have Establish the Next Target Condition. Here, again, the coach practices assisting the learner to develop a target condition that advances toward the challenge; is achievable; and is challenging.

While novice coaches can struggle with this, the structure of the Improvement Kata gives them a framework for comparison. In addition, the learner’s progress itself becomes data for the coach’s experiments of learning.

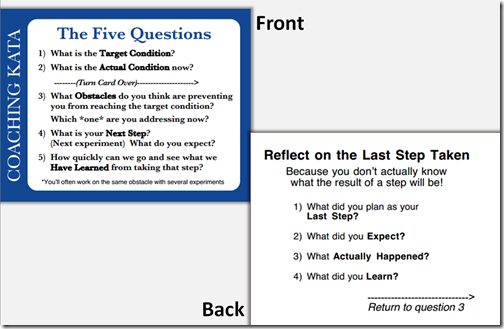

Of course questioning is the hallmark of the Coaching Kata. We have the “5 Questions” to start with, and they provide structure for not only questioning but listening as well.

There is a critical difference between giving feedback and giving advice, and beginning coaches – especially those who have formal authority – frequently fall into the trap of “leading the witness” – asking questions intended to lead the learner to their preferred answer. Giving feedback, on the other hand, might be more focused on pushing a bit on untested assumptions or gaps in the learner’s logic or understanding of the chain of cause-and-effect.

Thus, someone practicing the Coaching Kata is learning to let the learner arrive at their own solution vs. leading them to one that the coach has in mind. These are all instances where a seasoned 2nd Coach can help by giving feedback to the coach about her process – working hard to avoid “giving advice” in the form of exactly what follow-up questions to ask. (Believe me, this is more difficult than it sounds, and at least for me, doesn’t get any easier.)

I am going to make an interpretation of encouraging a solution based approach and assume this means exploring the space of possible solutions with experiments vs. “jumping to solution” and just implementing it. I could be wrong, but that is the only interpretation I can think of that fits with the context of the other items on the list.

And finally are the softer skills of showing empathy and recognizing and pointing out strengths. I think it is unfortunate that these skills are typically associated with exceptional leaders – meaning they are rare. These are things I have had to learn through experimentation and continue to work on. But I think I can say that my own practice of the Coaching Kata has given me a much better framework for doing this work.

The Coaching Kata framework is certainly not the only way to develop coaching skills. We have been training effective coaches long before 2009 when the original book was published. And there are very effective training and mentoring programs out there that do not explicitly follow the Coaching Kata / Improvement Kata framework.

BUT I will challenge you to take a look at those other frameworks and see if you don’t find that their underlying framework is so similar that the difference is more one of semantics than anything else.

In my next few posts, I am going to be parsing a course I recently took that is just that.