Earlier this year, Sir Ken Robinson gave a great TED talk about the state of education in the USA. While his talk was about K12, nearly everything he says applies to how we grow and develop leaders.

Or stifle their growth.

He makes it clear that no teaching is taking place unless learning is taking place.

And he points out that if we create an environment that encourages curiosity, then we get creativity and learning in return.

But many of our organizations and institutions almost seem to be designed, instead, to discourage curiosity. If being wrong or incorrect has negative consequences, then the safest course to take is one which makes no commitments and questions nothing.

Robinson finally points out that the ability to grow and learn is in all of us. It is much more a matter of the right conditions than it is innate talent or skill.

I would like to suggest that creating those conditions, and that process of growth, is deeply embedded in nearly all of our cultures and in our very humanity.

This growth is what the management consulting business calls “change.” Change is a hot topic. There are bookshelves, file drawers and web servers chock full of advice on how to “change.”

But what are we really talking about? Though we discuss “organizational change,” I think the process of “change” is deeply personal to each individual. It is a process, not so much of adopting new behaviors, but of personal growth.

And as individuals grow, connections between them strengthen, and the organization as a whole performs. But it’s people that change. And that change, more often than not, comes down to growth and confidence in the face of adversity.

So how, exactly, do people “change?”

Let me tell you about Karen.

She is a typical supervisor in a typical small manufacturing company. The company could be anywhere.

Karen is responsible for the shipping department. She oversees the work of about half a dozen people who process customer orders, pick the items, package them, label them, pack them and ship them.

As straight forward as this sounds, the real world throws a lot of chaos at Karen every day. They don’t know how many orders they are going to get, yet Karen must maintain a reasonable level of productivity.

Some orders are simple, others are complex with multiple packages being consolidated into a single shipment.

Sometimes the items aren’t on the shelf even when the computer insists they are.

A typical day for shipping was a continuous push to get the orders picked as soon as possible, then a push to get the orders packed, then there was the Big Push at the end of the day to try to force everything through the shipping process and ready for UPS.

Karen was coming in at 2 or 3 am to sort through paperwork and try to organize things. During the day she was working to manage the Big Pushes, move people to where the work was. And at the end of her 13 hour day she went home exhausted. And the next day she got to do it all again.

Meanwhile, in the background, a storm was brewing. We had identified an opportunity with great potential for productivity in manufacturing and shipping. But for Karen, that “opportunity” meant her team had to take on higher volumes of work with no more predictability than what they were already struggling to get out the door.

Let’s just say that Karen was skeptical. She was convinced there wasn’t any way, short of increasing her staff, that this could be done.

Karen was a good sport though, and grew into the challenge of learning how to break down and analyze the work steps, and get on-by-one flow into place. It was a lot of work as she tried some things that didn’t work in order to learn more about the things that did. Throughout this process, she was getting support, encouragement, advice and coaching from a couple of key, experienced people.

But it was Karen and her team, not her coaches, who were solving the problems because it was Karen’s team who had to live with the solutions.

A few weeks later I was back, and we were taking another team from another department through the same process. To give them a visible example of what to strive for, we went to shipping to let Karen show them the changes they had made, and were continuing to make, and explain the new work flows.

It turned out that one of the people getting that little tour had done Karen’s job a few years ago. Her first question was “Is the computer down?”

“No,” said Karen.

“Are you having a really slow day then?”

“No, in fact this is a pretty busy day,” was the reply.

“But…” with an incredulous look “… it’s calm.”

And yes, it was calm.

In addition to the process changes, Karen was leading differently.

Instead of being “Hurricane Karen” and disrupting the flow of work with constant intervention, she was starting to trust the flow and visual controls to tell her where she needed to pay attention.

When she was surprised by something, she was asking “What would have let us spot that issue sooner?”

She was beginning to manage problems and exceptions with an eye toward preventing them.

Her new skills were still rough and needed practice, but she was working hard to apply them. She was still getting a lot of coaching, but it was mostly to help her stay on track and not get distracted from the path by the urgent.

There was still a looming challenge, however.

While the new process had dramatically improved quality and productivity, the “one order at a time” rule that made it all work had the side effect that the pickers were doing a lot more walking up and down the aisles.

Karen was feeling a lot of pressure to go back to picking batches of orders. She challenged her coaches, and they challenged her to look at why the walking was necessary in the first place.

They found fast moving items in locations at the very back of the store;

And long one-way aisles with no cut-throughs and no room to turn around a cart;

The locations were poorly marked, increasing the time to search for something.

Pulling and picking one order at a time wasn’t causing more walking, it had highlighted the poor organization of the storage area.

Holding the line here took a lot of courage. Karen had to step up her leadership and gain the faith of her people.

She also had to learn to work with other parts of the organization to:

- Get slow moving and obsolete items off the shelves to free up space.

- Get a more rational location system into place.

- Take advantage of the increased shelf space to open things up; put breaks and cross-over points in the aisles; and create wider aisles where carts could pass one another.

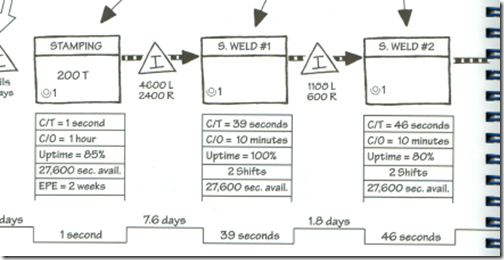

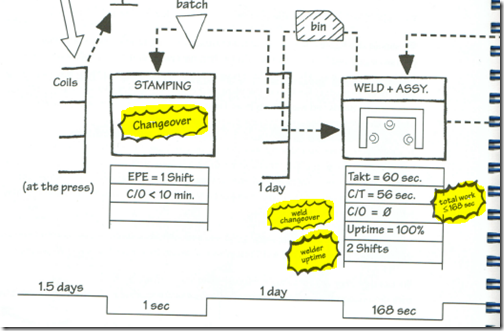

This was new territory, technically and politically. As a side-effect, the company had the insight that working on their changeover times in injection molding would have a direct effect on how much walking parts pickers in shipping had to do. I’ll let you figure out why those things are tightly related.

Some months later I was back again, and of course went to see Karen.

Now she was telling me about her initiative to take on even more volume by creating capacity from wasted time.

Karen had observed that they spent a lot of time counting out little parts into bags. Working with her team, they had developed a simple, inexpensive, part counting jig that mounts on the cart. They worked this out through a series of trials and experiments, solving one problem at a time, cut the counting time by around two thirds.

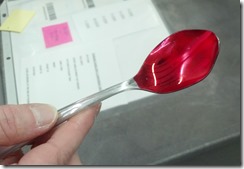

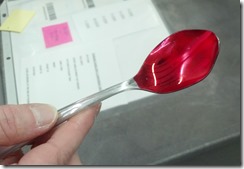

See that red spoon? Some of their parts are silver, others are white. And there are other colors as well. Their experiments had shown that candy red gave the best contrast between the parts and the spoon used to scoop them from the counting tray into the bag (even the red ones), thus reducing the opportunity to mis-count.

See that red spoon? Some of their parts are silver, others are white. And there are other colors as well. Their experiments had shown that candy red gave the best contrast between the parts and the spoon used to scoop them from the counting tray into the bag (even the red ones), thus reducing the opportunity to mis-count.

Who has time to think through this level of detail?

Karen and her team do now, because getting the daily work done is a matter of routine rather than a daily battle. She has time because, through her leadership, they have created that time. She took this last initiative on her own. She took what she had learned, and is now applying it every day.

When we talk about “change” this is what it looks like. It is people that change, and when they do, the organization changes with them.

Most of us have stories like this – of someone we know who was initially reluctant or skeptical;

Who overcame those initial doubts and committed themselves to a course of action into the unknown;

Who worked through a series of challenges, overcame them, and emerged change in some small, or large, way.

We find these stories compelling… but why?

This is the story of

The Karate Kid

Harry Potter

Dr Grant in Jurassic Park

Huckleberry Finn

It is the story of Beowulf, of Dorothy Gale, and Gilgamesh, of Alex Rogo in The Goal, Tom Hank’s character in Castaway and the real-life story of Apollo 13.

Snow White, Cinderella, Sarah Conner, Luke Skywalker, and on a grand arc, even the story of Darth Vader.

The story is told and set on sailing ships, star ships, in little cafes in Morocco, and across countless urban legends.

It is a narrative that is embedded in the psyche of every human culture from the dawn of storytelling.

And it is the continuing story of Karen.

Some of you may have heard of Joseph Campbell. His work became well known after a series of interviews with Bill Moyers in 1988, broadcast a year after Campbell’s death. The most famous of Campbell’s work is The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Campbell found common elements in nearly all mythology and stories across all human culture, throughout human history.

We tell these same stories, with different twists and forms, over and over. But they all have a similar underlying structure.

This isn’t about a formula for story creation, rather, our compelling stories follow the path taken by those we admire in real life. The stories and myths are concentrated for effect, but the transformation is the same. Although there are a lot of variations, there are some patterns of common elements.

What makes them compelling is growth through perseverance.

The Dragons, Orcs, Wicked Witches and Grendel all represent our inner fears and doubts.

What makes the “hero” – and our emerging leaders – is the willingness to set aside those fears and take on the challenges.

That, in turn, produces growth – what we call “change.”

It is individual people that change, and in the process of changing, they often follow their own “Hero’s Journey.”

The Mundane Life

The stories start with the protagonist leading an ordinary, often mundane life. He or she may be satisfied with that life, or may be yearning for something more.

Dorothy is on the farm in Kansas dealing with the demands of her aunt, and her little dog getting into trouble, dreaming of somewhere over the rainbow.

Sarah Connor is a waitress in a diner, and Bilbo is enjoying his days sitting outside and contemplating the scenery.

Nothing about Karen’s work life was mundane, every day was a new battle. But the battles were fought over and over. Victory was survival until tomorrow morning.

The Call

Early in the story, the hero often receives “the call” to depart the ordinary life into something compelling but unknown.

Sometimes “the call” is a violent event, like a tornado carrying the house to Oz. Other times it is an opportunity to “take the red pill.” It could come in the form of a change in the dynamics such as the arrival of Buzz Lightyear in the toy box.

Karen’s “call” was being asked to participate in a kaizen event to examine the very work that she managed every day.

Refusal of the Call

Often the hero initially refuses the call. Karen was very skeptical.

They often do not feel up to the challenge being issued, or feel they cannot leave their current responsibilities.

Nevertheless, in our stories, the call is eventually answered, and sometimes events compel the protagonist to act.

This is a point in the development of a leader when we must have empathy.

We have to realize that the known, no matter how ugly it may be, is at least predictable and safe.

Karen knew she had to come in at 4 am every day, and she knew she would be battling to keep things on track.

She knew she would be there late to make sure everything got done.

And she knew that the process would utterly fail if she did not do these things.

It was completely reasonable for her to be skeptical that it would be possible to change this dynamic.

Sadly, too many of us are quick to frame these reasonable fears as “resistance to change” and make judgments about the protagonists in the story unfolding in front of us.

But our reluctant heros-to-be are holding the best interests of the organization in their hearts. What we call “resistance,” most of the time, is actually fear of letting people down. We need to empathize with this fear because it is in all of us. In other conditions, that same fear also motivates great heroism and sacrifice.

The Mentor Figure

In a real-world organization we are all too willing to abandon people into stressful situations and expect them to step-up. In my own studies of world-class management systems, though, I have found a common theme:

The primary responsibility of true leaders is to coach and develop people.

In The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, Gandolf represents the mentor or spiritual guide. In The Goal this role is played by Jonah. We see Tinkerbell with pixie dust, retired Jedi Knights, and fairy godmothers.

The mentor cannot actually be the hero, but is highly influential in the hero’s development by providing guidance and emotional support.

In our story, Karen’s “Gandolf” was Brian, the Continuous Improvement Manager. This role, however, is temporary for Brian. Ultimately this role falls to Karen’s boss, Carlene. But Carlene is on her own journey as this company was still in transition.

Brian took on the role of giving Karen the training and guidance to help her along her journey.

This is very different than sitting her down in a class and deluging her with PowerPoint slides about general principles.

Though only Karen can lead her group, Brian was there to make sure she succeeded.

Crossing the Threshold

In the Hero’s Journey there is usually a moment when the protagonist steps from the ordinary world into the world of adventure and learning.

Campbell calls this “crossing the threshold.

After the tornado drops her house into Oz, Dorothy opens the door and sees and world of Technicolor. “Oh Toto, this isn’t anything like Kansas.”

Luke Skywalker goes to the bar to meet Han Solo.

John Dunbar moves to the Sioux village.

Karen entered the kaizen event on Monday morning.

The Journey of Adventure

Of course, “one does not simply walk into Mordor.” Actually you do. But there are obstacles to overcome.

The new world is different, and our hero must learn its rules, find new friends and allies, and overcome new challenges that usually increase in drama and complexity.

These events and experiences shape the growth of the character as he transforms.

As leaders develop, their styles and approaches change. They must. When leaders change their style and role – like Karen – they still face challenges from the people around them.

Karen was developing and testing new skills. She had never been taught how to carefully study how the work was done. We taught her.

She had not considered how smooth, steady work was faster than pushing everything. She learned by trying and experimenting. We taught her these things by teaching problem solving in the context of what she was trying to get done.

The emerging leader must be willing to learn, which means being willing to try something she doesn’t know how to do, and fail a few times.

The Mentor’s job is to shape the path forward and provide support, technical and emotional, throughout this process.

During this part of the journey, the hero usually acquires something – what Campbell calls “the elixir” but it may be symbolic and take the form of new knowledge or skill, or a great insight.

Karen’s “elixir” was developing faith that it was possible to calm down the chaos of shipping, to see problems sooner, and deal with them before they turned into disruptions.

The Final Confrontation

In our mythology, there is often a Big Confrontation toward the middle or end of the story, a symbolic death and rebirth. The protagonist must draw upon the strength that was gained up to this point, and emerges with new confidence, a changed person.

Dorothy had the courage to stand up for her friends and confront the Wicked Witch who, back in Kansas, had been trying to take her dog away.

Even though things were much better, Karen was confronted about the additional walking, and had her meddle as a leader tested. Where she might have argued in the past that this wasn’t working, per perspective was now “How do we move this forward?”

The Journey Home

Now the hero must return. Often there is yet one more confrontation and a final chase scene.

The hero re-enters the “old” world, but profoundly changed. Sometimes the world itself has changed, other times the protagonist’s response to that world has changed. Either way, things will never be the same.

Sarah Connor was no longer a waitress in a diner. She was tough, alert, and protecting the future savior of humanity.

Karen was learning to delegate the things she had previously done personally, and allow the process to handle them. Her management style has shifted from “Who is doing what?” to “Is the process working as it needs to?”

Oh – and maybe she doesn’t see it, but I do. Her mannerisms have changed. She is far more articulate and confident.

Why did I take your time to map this analogy?

When I read Jeff Liker’s book that describes Toyota’s process of leader development, what really struck me was the principle of self development combined with stepping up to the challenge.

A prospective leader is offered a challenge to take on a project that is likely outside of his or her current experience and knowledge base. While there is, without a doubt, an urgent business imperative, it is also a process of developing leaders.

The challenge is probably scary. The prospective leader has an opportunity to refuse the call and remain in her current job for the remainder of her career. There are certainly people who are very happy working on the assembly line until they retire. There is no prejudice here. How you reach fulfillment in your life and career is a decision as unique as your DNA.

But if the “challenge” is simply “make the numbers or we will find someone who will” the story can fall apart. Yes, there are truly exceptional people who can dig out of those challenges on their own. But they are rare.

We have to realize that, even in our adult post K12 world, our organizations must be institutions of learning.

And the way people learn is through experiences. Not just any experiences, but experiences that illicit specific emotions. It is the act of struggling with something we almost get that resets the neural patterns in our brains.

Today, we know how to teach emerging leaders to become critical process thinkers.

We do it by teaching routines that, once mastered, become thinking patterns. We guide them through that struggle in a kind, supportive, challenging way.

You may remember “Wax on, Wax off” from the classic motion picture Karate Kid (or perhaps you recall “Hang up coat” from the recent remake). Those basic motions were used to build strength and motions that could be carried out without thinking. In Japanese martial arts, they are called “kata.”

Thanks to research by Mike Rother, published in his book “Toyota Kata,” we are actively experimenting with a “kata” for learning foundational problem solving and leadership skills.

But this learning does not occur without motivation and perseverance. If we want to grow leaders and innovators, we have to understand that each of them must go through their own Hero’s Journey and emerge in their own way.

The path is not known beforehand.

What we can do, though, is recognize the pattern of human growth, support it, and create the best possible environment for people to find their path.

___________

Update: August 20, 2015 – two years later. I saw Karen again today. She is now overseeing the assembly department, which is much more complex. Her successor in shipping was telling me about her challenge to improve counting accuracy for larger orders (~100 small parts). The journey continues.

Another update: Karen is now overseeing injection molding, the most critical value stream in the company. Her first step there was to make sure the work schedules were realistic, visible to all, and to begin understanding what obstacles were coming up to prevent attainment. Then she started working on them.