Anyone who is following this blog knows my view of “engaged leadership.” As I read this book, I had two experiences.

Anyone who is following this blog knows my view of “engaged leadership.” As I read this book, I had two experiences.

- I found it validating. There were a lot of times I said “oh yeah!”

- I found it clarifying. Rother turns up the contrast on a couple of crucial points and I liked that.

This is not to say I don’t have a couple of quibbles, but I’ll get to those at the end.

The bottom line is that I am pushing this book, hard, internally in my company right now as a way to get a focused conversation going about what we mean when we say “engaged leadership.”

A Caveat

Before I get into this, I want to be clear about something. There have always been individuals and small groups out there that have had a deep, intimate understanding of how the Toyota Production System works and how to teach it. What I will be commenting on here is our community’s success at getting that deep understanding into the mainstream of thought. For example, “The Machine That Changed The World” revealed nothing new to anyone who had been teaching and practicing this stuff for a decade. What it did accomplish, however, was moving the discussion into the mainstream.

Thousands of people inside, and outside, of Toyota have been following some form of the practices Rother outlines for many decades. I have seen for myself the results of just trying to follow these practices. (The results from doing it badly are vastly superior to those gained from not trying.) Toyota Kata is an opportunity for at least a fundamental understanding of these practices to spread and hopefully generate a bit of a shift.

So, this review is not intended to say to anyone who has been successfully applying these skills that you didn’t know what you were doing. Quite the opposite. It is a validation of what you have been doing. The mainstream press is finally saying “ah-ha!” and understanding just how critical this is for sustaining and success.

Rother’s book describes a crucial piece that is simply not addressed well in any of the “lean industry” publications. That is the good news. The bad news is that it is going to be enormously difficult to get this piece into place in most companies. I’ll get into why later on.

History

The Toyota Production System was never designed. There are no specifications or blueprints. It grew, and continues to grow, organically. We learn about how it works by studying it. Therefore, our knowledge and understanding should be continuing to evolve and grow, as indeed, the TPS itself continues to evolve. Anyone who says “We get it now” has stopped learning.

In the early days we looked at the TPS through the eyes of engineers. We regarded it as a machine. If we could just see all of the parts and pieces, and understand how they work, we could reverse engineer the machine. That is where we get the emphasis on the tools, like one-piece-flow, pull, “looking for waste vs. value-add,” standard work and such.

In his doctoral research, however, Steven Spear took a different look. He went in with social science eyes rather than engineering eyes. His doctorial research findings have been cited as “potentially the most significant research ever to come out of the Harvard Business School.” Spear discovered the connections that make the mechanics into a living thing that engages people in improvement. His work is summarized in “Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System” published in 1999.

That was 11 years ago.

Unfortunately, in the meantime, other publications of the “lean industry” have continued to imply that “all you have to do is…” and describe sequences of using and implementing the tools. This has been at best misleading, and resulted in a graveyard of failed efforts to adopt the TPS.

Everybody, though, has been clear that “engaged leaders” are crucial for success. But up to this point, nobody has really said what the term “engaged leaders” means in terms of what they actually do. There have been hints – John Shook’s Managing to Learn does a great job describing the process of mentoring, but does not set the context as well as Rother does.

So my first key point is that I believe Toyota Kata is a significant contribution to the popular body of theory – it is the first book that really describes, in detail, the mechanics of “engaged leadership” in a continuous improvement environment.

Kata

The term kata is found mostly in the study of Asian martial arts. Kata are the basic motions, “wax on, wax off,” that are foundational building blocks. Once those foundations are embedded into subconscious memory, it is no longer necessary to focus on them. Though they are not called kata, the basic drills that any athlete learns are foundational in the same way.

Rother contends that Toyota’s improvement processes are build upon two fundamental kata.

- A kata for improvement or problem solving.

- A kata for coaching.

This does bring up my first quibble about the book. I wish it had a different title. While it is a great metaphor, I have found that the word “kata” is foreign to many people and I end up having to spell it and explain it as I tout the book. I ran into he same thing with Spear’s book Chasing the Rabbit – having to explain what the rabbit is and why we are chasing it – and note that his book has been re-issued with a title that better explains what the book is actually about.

Context

A “kata” is just a practice – in effect, yet another tool. There are lots of books and materials out there for problem solving methods, and John Shook’s Managing to Learn does a decent job describing the coaching process. So what is new here? In my opinion, Rother does the best job so far of setting the context – describing the improvement culture and environment if you will – of any popular press publication so far. It is this context that I find lacking in so many of the publications coming out of the “lean press.”

The book covers five interlocking topics.

- The role of vision and direction in continuous improvement.

- Critical context for the “classic lean tools” as target conditions.

- The problem solving kata, and how it differs from what most of us do.

- The coaching kata, really describing how management engages.

- A proposal for teaching the problem solving and coaching kata to a management team.

In addition, there is an overarching theme which compares this style of management with what is traditional taught and practiced in most business.

I would like to discuss these in detail, and offer my thoughts on each of them.

Vision and Direction

Maybe you’ve been there. “Top management” makes a “commitment” to “use lean principles” or some such. But nobody ever really defines what that means. The implementation is delegated to staff specialists, and it is up to them to provide “management education” and, ultimately, make the case for each and every improvement step.

I suppose there might be cases where this approach has worked and sustained. I just don’t know of any.

In the Toyota that Rother describes, there is an an overarching sense of direction, the true north that is used to unify the organization’s understanding of what “improvement” means.

Although Rother describes Toyota’s concept of being a perfect supplier much the same way that Spear does, (zero defects; 100% value added; one-by-one, in sequence, on demand; security for people) the concept comes through in other companies in other forms.

In “Made to Stick,” for example, Heath and Heath cite a story about Herb Kehler, then chairman of Southwest Airlines, as he describes how he uses a simple concept of the ideal to make decisions. In his case it is “We are the low-fare airline.” Thus, any “improvement” that does not consistently move Southwest in that direction is considered off track. (I should point out that “…without compromising safety or consistent performance in any way” are likely unspoken “givens” in this example.)

In The High Velocity Edge (formerly titled Chasing the Rabbit), Steven Spear points out several examples, including Toyota, where there is a strong explicit, or implicit, sense of an uncompromising direction. And Jim Collins’ book, Good to Great talks about defining what “we will be the best in the world at” as one of the key factors to sustainable breakout.

So, again, while this is not a new concept, Rother turns up the contrast and elevates it to a prominent position in decision making and direction setting.

Why is this important?

Because it focuses the debate away from “should we do it” to “what problems are in our way?” Rother gives a great example on page 50 and 51:

… we pointed out the potential for smaller batch sizes to the management team. … closer to 1×1 flow, less inventory and waste, faster response to different customer requirements, less hidden defects and rework, kanban systems become workable and so on.

Almost immediately the assembly manager responded and said “We can’t do that,” and went on to explain why. [… the usual excuses here …] “Those extra non-value-added activities would be waste and would increase our cost. We know that lean means eliminate waste, so reducing the lot size is not a good idea.”

The plant manager concurred, and therein lies a significant difference from Toyota.

A Toyota plant manager would likely say something like this to the assembly manager.

“You are correct that the extra paperwork and first-piece inspection requirements are obstacles to achieving smaller lot size. Thank you for pointing that out. However the fact that we want to reduce lot sizes is not optional nor open for discussion because it moves us closer to our vision of a one-by-one flow. Rather than losing time discussing whether or not we should reduce the lot size, please turn your attention to those two obstacles standing in the way of our progress.”

By clearly defining what “progress” is – outside of the scope of the daily debate – the debate is shifted away from whether or not there is a problem to a discussion on how best to solve it. This, in my view, is one of the most important policy decisions a management team can make. It gives people a foundation of consistency. But for this to work, there must be no caveat such as “when it makes sense to do so.” Adding one provides an “out” that allows people to accept the status quo rather than focusing people’s attention in solving the problems so it does make sense.

Rother goes on to point out how this sense of direction re-shapes cost-benefit analysis. The question being answered is now not whether we will make this decision, but rather whether the solution is adequate, or we must keep looking for a better one.

Step by Step

A common source of confusion in organizations trying to adopt these principles is the tension between the theoretical ideal or vision (as defined above) and the “what we can do now.” This is made worse when there is no clear sense of the ideal vision or direction because it reduces each step to a choice of “do we take it?” rather than “what must we do to get there?”

What happens in that case is some people are talking about the vision, others dismiss it as “unrealistic” and a lot of energy gets expended because people think the vision is something that must be achieved with a single comprehensive plan..

In reality, though, no one has any idea what the clear path is. Trying to build a detailed plan to “implement lean” is destructive because there is no way to predict what problems will need to be solved until they are encountered. If you think about it a comprehensive project plan assumes that we have such a clear grasp of the current condition and already know what must be done to get us to the desired end state. In reality, we are driving on a winding road in the dark. We can only see as far as our headlights.

“We’ll just solve the problems before we discover them”

– Dilbert

Rother describes a series of target conditions as the true objectives of improvement.

Because there is a strong sense of direction, it makes sense to set an immediate target just beyond what we can achieve today. While there is no clear path to the notional end state, the target condition is much closer, so the immediate issues that must be overcome are plainly visible.

While this is somewhat understood in general principle, Rother takes it down a couple of layers. He points out that each of the common “tools and techniques of lean” are actually targets to strive for. Only by setting an objective, and then trying to hit it can we learn why we cannot. That, in turn, becomes the focus for kaizen.

The example that will most challenge a lot of practitioners out there is takt time as a target condition. This is one of the few mainstream books that gets beyond the overly-simplistic notion of takt time only as the rate of customer demand. Rother acknowledges that, internally, there is an intentional overspeed built into the system as a target. And here is the key point: You rarely hit the target. At least not at first. It is established as something to strive for, step by step, each day. The system is set up so people can both succeed in meeting the customer’s needs every day and have a challenge for the next level of performance.

From this foundation, Rother expands the concept across the other “tools of lean” – not as things you implement, but devices to focus your attention on the next problem. The common excuses and obstacles we are used to hearing are turned around into those challenges. The work cycle is too unbalanced to achieve one-by-one flow? OK – then that is the focus or our kaizen activity until we break down that problem. The kanban discipline broke down? Great! What didn’t we understand when we set it up?

In each case the questions are:

Can we run this way? (smooth, level pulls; one-by-one; cycle time = takt time; etc)

If no, then “What is preventing us… now… from doing so?” Crutch the system while you work on the problem, but work on the problem. Rather than using the problem as a barrier, it become the next challenge.

Rother goes into quite a bit of detail for each of the common tools, and resets the commonly held idea that they are something to implement. I am glad for this chapter because it clarifies (or contradicts?) the idea that these tools are “what makes a value stream lean.” That idea has been firmly entrenched by the middle chapter of Rother and Shook’s book Learning to See which, in turn, is the cornerstone of the LEI’s publications and doctrine. We are finally starting to move beyond that anchor and understand that these tools are not the fundamentals of lean.

The entire concept of a target condition, that describes not simply the performance but the operating characteristics of the system, is a critical one. The vision of ideal sets the general direction for forward progress, the target condition issues a clear done-or-not-done challenge for the next step.

This concept links back to Learning to See in that the “future state map” can define an overall target condition rather than some long-term end state. Perhaps that was the intention all along. But Learning to See and its publishers are vague about that, and many companies have tried to reach too far into the ideal with their future state with the idea that it describes an end game rather than the next challenge.

Kata 1: Problem Solving

Of course if the target could be achieved today, it is a poorly set target. There are likely problems to solve.

Where we commonly fall short in problem solving is trying to take on too much at once. We try to take on complex problems, create elaborate dependencies, and work on multiple things at the same time. As a result, we never really gain a clear understanding of what worked (or didn’t) or why because we are manipulating all of the variables at once.

Unfortunately most “problem solving” courses teach us to do it just this way.

Rother, on the other hand, points out that rapid, linear solution of small problems, focusing on single issues and single countermeasures, lets us gain that process understanding – and increase our profound knowledge in the process.

A really telling chart on the crucial difference between a problem solving culture and a problem avoiding culture is in the section titled What Toyota Emphasizes in Problem Solving.

|

Toyota |

“Us” |

| Focus |

Learn about the work system.Understand the situation. |

Stop the problem! |

| Typical Behavior |

Observe and study the situation.Apply only one countermeasure at a time in order to see cause and effect. |

Hide the problem.Quickly move into countermeasures.

Apply several countermeasures at once. |

This little chart covers a lot of ground. Where “we” are primarily interested in eliminating the effects of the problem so we can move on to something else, the Toyota approach, according to Rother, is to learn and understand more about the process. So while solving the problem is the goal, it is only acceptable to solve it in a way that improves understanding. A blind solution is no solution.

Logically, of course, this makes sense. But in real life it is extraordinarily difficult in the heat of the moment, with people demanding a quick fix, to exercise this kind of discipline. This is driven by a fear that thorough = slow, which is simply not true.

And as each countermeasure is applied, the next problem becomes apparent – and that problem is the next barrier to better performance. Progress can be made very quickly in this way because there is a much reduced risk of leaving problems behind us as we move forward.

In contrast, I find two main issues with most “problem solving” approaches.

First, they spend an inordinate amount of time deciding which problem to work on. While that may feel like working on solving problems, no actual progress is being made. The countermeasure for this waste is to have a clear sense of direction, and a clear target objective that makes “which problem to work on” painfully clear – it is the obstacle between the current state and where you want to go.

Second, and perhaps worse, is that we like to think we are working on “important” problems, which seems to mean difficult ones. Maybe this is because if feels like a waste of time to work on the simple issues. “Problem solving” is often taught as a complex, drawn out process (which often begins with deciding which problem to solve…). We learn about designed experiments, statistical analysis, stratification techniques. Some problems require this kind of work, but not very many. Worse, learning to solve those problems well requires a thorough grounding in the fundamental logic which is best learned by solving lots of problems.

The only way to solve lots of problems is to start with the simple ones, but apply rigorous methods in doing so. But we skip that part, and then wonder why “problem solving” doesn’t take hold. We are trying to teach multivariate calculus before we learn algebra.

Toyota avoids this issue because they develop these skills from the basics, at the very start of their employment. Teaching the fundamentals – the entry level stuff – to senior people with advanced career positions can be problematic. More about that later.

Kata 2: Developing People (Coaching)

Even in the rare organizations that have fantastic problem solving and kaizen skills, the development of people often a very weak process. There is no systematic approach to doing it.

Let me be specific about this, just to be clear.

Most companies have some kind of “performance management” system that is built around some form of “management by objectives.” The team member is supposed to develop a set of goals with his boss. Those goals may even include “developmental goals.” They might even be specific things like taking a class or performing an assignment. Then, at the end of the rating period, the team member is evaluated on his performance against those goals.

This is not developing people. Not by a long shot.

“Coaching” is often a euphemism for the boss telling the team member that something in his behavior or performance is seriously inadequate. It is the first step in the “steps of accountability” which, in itself, is a euphemism for escalating punitive actions on a path to termination for cause.

This is not coaching. Not by a long shot.

And both of these functions are usually delegated to Human Resources rather than being clearly owned and adminstered by line leaders.

Rother, on the other hand, describes a process of mentoring. The boss has skin in the game because he is accountable to his boss for the results. Yet he does not direct solutions. He guides the subordinate through the process of solving the problem in the correct way. In fact, upon study, it becomes clear that the process of coaching (the “coaching kata”) is simply an instance of the problem solving kata. There is a target condition for the team member’s capability. The current condition is understood, gaps are assessed, and at each step of the way, countermeasures are applied in the form of direction that will build the team member’s problem solving skills. In the end, it is the team member, not the boss, who comes up with the solution, and the boss has to live with whatever it is as long as it works.

What is critical to understand here is a difference in who carries out improvements. In most of our companies, improvements are the domain of skilled staff specialists. These are the people who plan and lead kaizen events, or carry out black belt projects, or whatever improvement process is used. Those people are probably quite good at what they do, but they are the only ones who do it. The attention is always on solving the problem. Yes, they go through the motions of developing people – they teach them the principles, they guide them to the correct solution, but in the end, the process of how to improve is the domain of the specialists.

This is, in reality, a very traditional approach – a slight evolution from the practices outlined by Fredrick Taylor in 1911. Yes, they do a better job of “engaging the workers” vs. just telling them what to do, but when that engagement is limited to specially planned events, we are really not developing anyone, nor are we truly engaging them.

In a Toyota Kata type environment, most improvements are led by lower level line leaders, and they do so in way that is designed to develop people’s depth of knowledge. Yes there are staff specialists, but they are pulled in when a problem requires technical help rather than being pushed in to “fix things.”

The other key point is that in the Toyota-type environment, the entire operation is built around flagging problems immediately. Spear describes how work, information flows, material flows, and indeed the flow of problem solving itself is deliberately structured to always be testing against an explicit intent.

In this environment, the vast majority of problems are discovered and handled while they are relatively small and manageable. In contrast, “traditional” organizations deal with problems only when they can no longer be tolerated. Where Toyota deliberately stops the process at the first hint of trouble, other organizations run it until it is so overwhelmed that it is brought to its knees.

Following that, in the Toyota-environment, someone other than the production operator responds to the problem. This, again, is a huge contrast. But if you think about it, the only thing the production worker can do is work around the problem enough to keep moving. He doesn’t have time to solve it and continue production. So when we say “We want out workers to see problems and solve them” that may be well intentioned, but it isn’t going to happen without the rest of the structure in place.

What this means is that there is no such thing as an entirely autonomous worker, nor can there be a “self directed team” that operates completely independently. Trying to do so is leaving people on their own, without support from the rest of the organization. That doesn’t mean we micro manage, but it does mean that there is a clear delineation between “normal” and “abnormal” and, further, “abnormal” demands that someone gets notified right away, and responds in a specified, standard way.

The role of leaders in this world is two fold.

- Respond immediately at the first hint of a problem. Take ownership of the issue. Get the problem cleared – that is, establish a temporary countermeasure which allows safe, defect-free production to resume.

- The problem has revealed something that was not previously understood about the process. Work together with the people in the trenches to develop that understanding and guide them through the process of implementing a workable solution.

The coaching kata is how this is done.

In the end, not only is the problem fixed, but the profound knowledge of the entire organization has improved.

A couple of things that make this different.

The initial temporary countermeasure will likely “bust the system.” By that I mean it takes things away from the ideal. But that happens all of the time, everywhere, doesn’t it? True, but what happens next is critical. The leader is responsible for the issue until the system is not only restored, but improved. Where “the rest of us” willingly accept that we have to compromise and make things a little less than ideal to get the product out the door, the Toyota Kata mindset accepts this only as a scaffold to hold up the process until it can be repaired… and strengthened so it won’t break again. With one mindset, things get a little worse. With the other, they get better. “Chatter is signal.”

Rother describes this process with a few stories and examples that make the point very well. So does John Shook in Managing to Learn.

Adopting the Kata

One thing I like about this book over many others is that Rother goes beyond just describing an ideal environment. In Chapter 9 Developing Improvement Kata Behavior in Your Organization he openly discusses the very real barriers that an organization must surmount to get this thinking and practice into place.

He says the challenge is:

“Not to implement or add on some new techniques, practices or even principles”

rather it is

“To develop consistent behavior patterns across the organization.”

He is, of course, talking about a fundamental change in culture. Let’s talk about that a bit. “Culture” is really defined, not so much by the behavior of individuals, but rather, it is something that emerges from the norms and rituals people follow when they interact with one another. This is true of a national or ethnic culture as much as a corporate culture.

The coaching kata describes a specific way that people interact with one another when solving a problem. It is not individual behavior – what we commonly teach in “problem solving” – it is group behavior. Therefore, this is not something that can be taught to individuals.

Rother is clear about a couple of things. First is that nobody has succeeded in doing this as well as Toyota yet. We are cutting new ground here. There is no clear path to the end state. There is a clear vision for what the end state looks like, and each of us should know (or be able to assess) the current state in our individual organizations. If this sounds familiar, it is. Rother is describing a process of using the very principles discussed in the book to put these patterns into place. Why? Because when the practices are applied correctly, they work. If they don’t work, we must look at the quality of our application, not the validity of the approach. “If the student hadn’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught.”

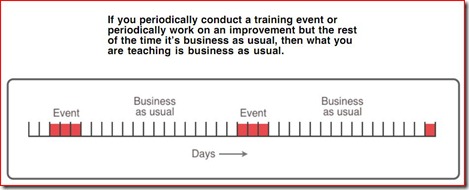

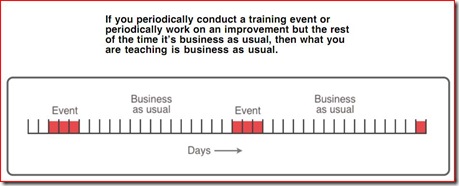

He is equally clear in a section titled What will not work.

- Classroom training does not work any better here than it would to teach you to swim or ride a bicycle.

- “Workshops” do not work – especially if they are focused on making improvements vs. developing behaviors. I’ll talk more about that in the next post.

- Hiring consultants to lead improvements for you, does not work.

- Using metrics to alter people’s behavior. Management by measurement does not work.

- Reorganizing, “re-engineering,” whatever you call altering the lines on the org chart, does not work.

What does work?

Continuous and conscious practice with the oversight of a coach. Every world-class athlete in the world has a coach. Only the coach can observe her performance objectively and see what must be adjusted to improve it. I always wonder why it is that, in business or operations, we believe that once some level is reached there is no need for this.

In this section Rother outlines what seems to be a pretty good plan for applying the improvement kata to the problem of developing the organization’s skills.

A couple of keys.

- Learn to do before learning to coach.

While this makes sense when we write it, again, in business organizations it seems that people’s capabilities to do something they have never done before are not questioned once they reach some level of seniority. This is, of course, silly. Rother proposes to start at the top with the basics – not because they end up as the primary coaches. No, that is primarily the domain of the middle managers and below. But because someone has to coach those middle managers, and it has to come from above. Rother’s point is around classic change management. I would add that starting in the middle puts those people in an untenable position because they are being taught to behave in ways that their bosses do not understand. Getting the top level team not only involved, but embedded, in the process is a countermeasure.

I am not going to go into a lot of detail and spoil the book. Get it and read it. Form your own view on this. Just understand that getting this thinking into place is a big deal.

Final Thoughts

This book is a good one, but I want to add a little reality here.

Like every book before it, Toyota Kata is targeted primarily at senior leaders. I would like to say that it will take off like The Goal or The Machine that Changed the World. It is probably too early to tell, but I don’t see it happening yet. Like most books of these books, its primary readers are going to be technical practitioners.

Those technical practitioners are the ones leading the classroom training, leading the kaizen workshops or black belt projects. They are the ones who are doing most of the things that do not work. They are doing those things because that is what their bosses expect (or allow) them to do since, rightly or wrongly, “improvement” is largely delegated to them.

Odds are you are one of those people if you are reading this blog, and odds are you are the only one who will be reading this book. It is a great book, but you will find it frustrating because you bosses aren’t reading it.

Here is what you can do.

First, practice this stuff on your own. Coach each other. It will feel awkward. Get as good at this as you can.

Then start altering how you run your events. Shift them to changing the behavior of team leaders and supervisors. Teach them to see, clear, and solve problems quickly. Set more clear target objectives. Hold yourself to a higher bar. At the end of an event, where you have traditionally focused on clearing newspaper action items, focus instead on ensuring that this behavior is embedded. Coach and support those front line leaders until they are habitually employing the kata every single day. That is the only way your results will sustain. Then, and only then, move to the next “event.” Your objective is not so much to make change in the way things flow as it is to systematically transfer this behavior to those critical first two or three levels in the organization.

Then comes the hard part.

The leadership above is going to say and do things that introduce problems. You have to intervene, but use it as a coaching opportunity. Apply the kata, just like you would for any other issue. Now, though, you are coaching those leaders – gently – through the process of understanding what is really happening, what they truly want to achieve, and understanding what is truly in their way. Maybe, just maybe a few of them will listen.

And maybe you can lead them through a study of this book so they can begin to understand what you are doing.

Just to be clear, Rother says that everything I have just said is the wrong way to go about this. It has to start from the top. Perhaps he is right. But sometimes you do what you can, where you can.

In the end, these concepts have to overcome huge momentum. Our business leaders today are firmly entrenched in a management paradigm that was developed, ironically, in General Motors. It is taught by every major business school in the world. Now we are beginning to see that there is a better way. But the better way is very different from anything they understand, and it is a lot of work. Its focus on developing people, first and foremost, runs counter to the paradigm of an objective, numbers-based analytical “business decision.” Ironically Toyota’s approach is based in far deeper understanding of objective facts than the financial-decision paradigm, but it does not feel that way when you are doing it.

Thus – this is a great book. Read it. Do what it says. But it isn’t going to move the Earth for us. There is still a lot of work we have to do ourselves.

I welcome your thoughts and comments.