A lot of the organizations I deal with have a legacy with Six Sigma, or some x-Sigma variant. If they are now trying to incorporate Toyota Kata as a way to shift their daily behavior, questions arise about how it fits (or might fit, or whether it fits) with DMAIC.

This sometimes comes about when the impetus to embrace Toyota Kata comes from outside the organization, such as an initiative from the corporate Continuous Improvement office. In this case, unless integration with legacy approaches is carefully thought through, Toyota Kata (or whatever else is coming down the pipeline) can easily be perceived as “yet another corporate initiative” or “something else to do” rather than “a new (and hopefully better) way to do what we are already doing.”

My Background

First a disclaimer. My deepest exposure to Six Sigma was during my time as a Quality Director in a large company that had a long history with TQM and then Six Sigma. Thus, I dealt with the Black Belts and Green Belts in the organization, and paid a lot of attention to the projects they were working on.

In addition, every certification project for a new Black Belt came across my desk. Unlike a lot of managers in the chain (apparently), I actually read them, parsed them, and asked questions when I couldn’t follow the story line of the project. (Apparently nobody expected that, but it’s another story.)

I worked with the corporate Master Black Belt, made input into their programs, and did what I could to create a degree of cooperation, if not harmony, between the Six Sigma community and the lean guys.

Thus I am not claiming this is anything new or profound. Rather, this is sharing my own sense of connection between these two approaches in a world where I often find them competing for people’s mindspace.

The Improvement Process Flow

As I observed it, a Six Sigma project was typically organized and conducted as follows:

An area manager, usually a Green Belt, identifies something that needs improving. He assembles a team of stakeholders. He is coached by a Black Belt through*:

Defining the problem and establishing a charter for the team.

Establishing a Measurement that will define progress.

Conducting a thorough Analysis of the process, with a primary focus on sources of variation, especially those which are intertwined with quality issues.

Developing a list or set of Improvements and putting them into place, again focusing primarily on variation in methods, etc. that drive defects.

Establishing a standard to Control the process and keeping it running the new way.

Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control. DMAIC.

In actual practice, it is very similar to the large single-loop “six step problem solving” process I was taught as “the problem solving process that came out of TQM.” That is probably not a coincidence.

DMAIC projects are typically targeted at measurable significant financial payback. Black Belts are trained to find and spend their time on high-payback projects. At least in the company I worked for, there was a minimum payback they had to achieve to get their certification. They also had to demonstrate knowledge of the various high-powered statistical tools.

It makes sense for people steeped in this methodology to ask how it fits in with “short cycles of experiments and improvements” that are the anchor for not only Toyota Kata, but kaizen in general (if you are doing it right).

And, put another way, if the organization is trying to establish a coaching culture using Toyota Kata, is Toyota Kata something different from DMAIC, or do they fit together? (I have actually been asked exactly the same question about Toyota Kata and kaizen(!), but that, too, is another story.)

To give credit where credit is due, this was the topic over lunch last week at a client site whose Six Sigma projects also follow the general structure I outlined above. Jazmin, the continuous improvement leader, was already working through this in her mind, and recognized the linkage right away.

Since the company has an active Six Sigma program, with dozens of projects ongoing, we wanted to find a way to integrate Toyota Kata thinking into what they were already doing vs. introducing yet another separate initiative. (It is easier to “embrace and extend” something you are already doing than bring something brand new into the domain.)

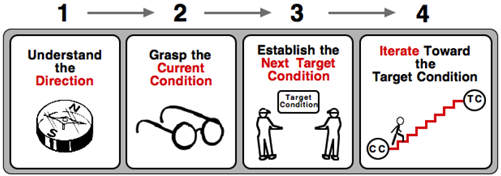

Relating DMAIC to the Improvement Kata

Here is how I relate DMAIC to the Improvement Kata.

Define the Problem =(more or less) Challenge and Direction. This is what we are working on, and why it is important.

Measure and Analyze = Grasp the Current Condition. Six Sigma has a host of powerful tools (which are often used just because they are there … so be careful not to make easy things complicated).

I would point out that if you follow the process in the Improvement Kata Handbook, you are also initially focused on variation in the process. Lean people tend to reduce all variation down to units of time, but in that noise are all sources of variation of the process. Defects, for example, don’t count as a delivery, and so introduce noise into the exit cycles. Machine slowdowns and stoppages, likewise, disturb the rhythm of the process. Like DMIAC, the Improvement Kata, as outlined in the handbook, steers you toward sources of variation very quickly.

Thus, a Six Sigma project team, and an improver following the Improvement Kata are both going to initially look for sources of instability. (Quality First, Safety Always).

At this point, the two diverge a little, but only a little.

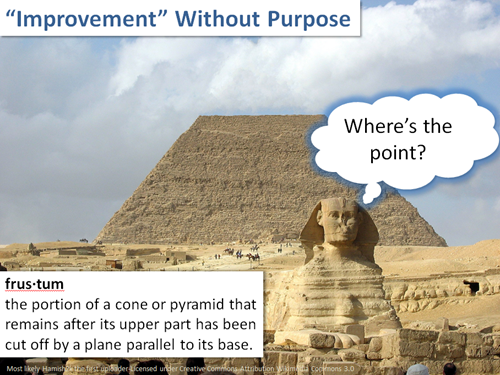

Perhaps because DMAIC sounds like a single cycle, a fair number of teams tend to try to Implement a Single Grand Solution. They spend a fair amount of time brainstorming what it should look like, and designing it. Then, once they think they have a solution, they put it into place by establishing new “standards” (in this context, that usually means procedures), training people, and validating that it all works.

Again – a lot of kaizen events do pretty much the same thing, they just might do it faster if it is a classic five-day event.

A few years ago I was on a discussion panel at a conference in Chicago that was very Six Sigma centric. In the various breakout sessions, the Black Belts (who are mostly staff practitioners) universally complained about “management embracing the changes” and not enforcing the new processes. They were frustrated that once they were done, things slipped back.

In other words, once the energy input of the project itself stopped, entropy took over, and things regressed back to the original equilibrium.

And (once again) traditional kaizen events often have the same problem.

Blending Toyota Kata and Six-Sigma Coaching

Think of this conversation between the Black Belt coach and the Green Belt project leader in their daily meeting and check-in:

[preliminary social rituals]

“Just to review, what is the problem you are working on?”

[Green Belt reviews the charter and objective]

“Great, so what is the target condition you are striving for right now?”

[Green belt describes the next intermediate step toward the chartered defined state. He describes how the process will operate when key parts of it are stabilized, for example.]

The Black Belt is listening carefully, and may ask follow-up questions to make sure the target condition is clearly on the path toward solving the defined problem vs. chasing something interesting-but-irrelevant to the issue at hand.

“Good. Can you tell me the last step you took?”

[Green Belt describes a change they made, or some additional data they needed to collect and analyze, or a control measure they have experimented with, etc]

“What did you expect from that step?”

[Green Belt reviews the intent of the action, and what he expected to happen.]

“And what actually happened?”

[Green Belt describes what his data collection and observation revealed about the process, or how well his control measure worked to contain a source of variation, etc…. or didn’t.]

“And what did you learn?”

[Green Belt describes insights that have been gained, especially insights into sources of variation, or the effect of controlling them. He also describes what he might have learned about the tools, or struggled with in applying them.]

“Very good. So what sources of variation or obstacles do you think are preventing you from reaching the target right now?”

[Green Belt describes the current suspects for causes and sources of variation in the process, as well as other issues that may be impeding progress.]

“Which one of those are you addressing now?”

[The Green Belt may well still be working on the last one, or might have it effectively controlled and is now addressing a new one. If he has moved on to a new one, the Black Belt is going to be especially interested in the control mechanism for the sources of variation that has been “eliminated” so it stays that way.]

For example, a follow-up question might be “Can you tell me how you are controlling that? What countermeasures do you have to detect if that variation comes back into play?”

We aren’t limited to SPC of course, and actually would rather have a binary yes/no need-to-act/don’t-need-to-act signal of some kind.

What we are going here is iterating through sources of variation, and establishing a positive Control on each of them before moving on rather than trying to stabilize everything in one step at the end.

Once he is satisfied that the project team hasn’t “left fire behind them,” then the Black Belt can move on.

“Great. Can you tell me the next step you plan to take, or experiment you’re going to run?”

[Green Belt reviews the next action to either learn more about a source of variation or attempt to keep it controlled.]

“And what result do you expect?”

[If the Green Belt is proposing using a specific Six Sigma statistical cool, the Black Belt is going to be carefully listening, and asking follow-on questions to confirm that the Green Belt understands the tool’s function and limitations, how he plans to use it, what he expects to learn as a result, and why he thinks that specific tool will give him the answers he is looking for.]

“OK, when do you think we can review what you have learned from taking that step”

This interaction is using the Coaching Kata script to develop the Six Sigma skills of the Green Belt project leader. We already have a coaching relationship, so all we are doing here is practicing a technique to make it more effective and more structured.

DMAIC is now more like:

DM [repeat AIC as necessary]

as the team works methodically through the sources of variation as they are uncovered.

The Master Black Belt

At the next level up is typically a Master Black Belt who is generally responsible for mentoring and developing the Black Belts. They typically meet weekly or monthly and review and share progress on projects.

Only now, let’s shift the discussion to reviewing and sharing progress on developing the problem analysis and solving skills of the Green Belts. Remember, the Green Belts are line management, and we want to get them thinking this way about everything.

“Lets review your learning objective for your Green Belt last week.”

“What did he do? What did you expect him to learn?”

“What did he actually learn? Did he make any mistakes?”

“Is he stuck anywhere? What is your plan to give him additional coaching or instruction?”

In other words, they are following DMAIC as well. Except that the “problem” is the skill of the Green Belt and how effectively he is applying that skill to solve his chartered problem.

I am really interested in hearing from Six Sigma folks out there about how this resonates, or doesn’t, with you.

————

*Sometimes I observed a Black Belt doing the same thing on his own initiative, leading the project himself. Occasionally I saw a Black Belt acting solo. I am not discussing either of those approaches here, however.