In Chapter 2 of The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership, Jeff Liker and Gary Convis describe one of the most important, and least emphasized, aspect of developing leaders – the necessity for intrinsic motivation. In simple terms, the desire has to come from within. This theme ties together everything else in the chapter, and I suspect, through the rest of the book.

On the other hand, this isn’t about the typical western “everyone fend for themselves” environment that develops unhealthy (and unethical) cutthroat competition.

They describe a nurturing environment that will allow and support anyone with the desire to take on ever increasing responsibility and challenges, and learn through a process of developing mastery.

The Role of Sensei

Not surprisingly, the role of the sensei described in Lean Leadership is quite consistent with the process that Jeff Liker and Mike Hoseus describe in Toyota Culture.

While the work environment itself is built around opportunities for learning, it is far different from out western ideas.

Lean Leadership sums it up quite well as they discuss the role of the sensei.

-

In the west, the teacher’s role is to show you the shortcuts.

-

At Toyota, his role is to make sure you don’t take shortcuts.

The teaching process is one of challenge and struggle – but not abandonment. It is guidance through discrete learning stages on the way to mastery.

Mastery

“Standard work” has always been regarded as a core element of the Toyota system. Liker and Convis build on the concept as far more pervasive than simple work procedures. We have known there is more to it for a long time, but like the list of what doesn’t work, authors, consultants and practitioners continue to emphasize the work procedure model.

In Lean Leadership, we see standard work as a path to mastery, and we see the reason behind the emphasis.

Liker and Convis describe a three stage process of learning and developing:

- Shu – being taught. In this stage, the teacher says “do this” and the struggle is to get it right.

- Ha – competent, but following by rote. In this stage, the teacher asks questions to cause reflection, and the struggle is to understand.

- Ri – mastery, the point where the team member has enough depth to improve upon and teach the task.

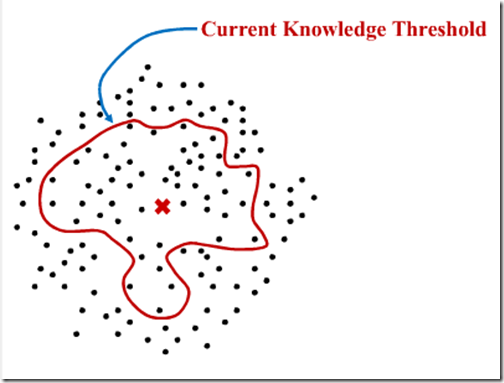

The point of standardizing and stabilizing a process is to allow the team member the chance to master it. Why is this important? Because then the team member can pay attention to solving problems to improve the work vs. solving problems to simply get it done.

Even this is fairly easy to grasp in the context of bolting a suspension together, or welding a scissor lift. But the same principles apply to leadership itself.

Mike Rother’s Toyota Kata is about application of this principle in the core processes of leadership: Problem solving and coaching. By standardizing problem solving, we give team members the opportunity to master it so they can focus on solving the problem rather than trying to figure out how to go about solving it. It sounds like subtle semantics, but it is a huge difference.

But, again, this is about demonstrated capability rather than classroom hours Compare this process with how we typically “certify” practitioners in the west.

At Toyota the learner’s capability is judged by direct observation, just like any other process. While there must be an internal drive to learn, the challenges and struggles are tailored for the learner’s next stage of development.

Self Development vs. Mandated Development

All of this brings us to one of the core differences in the Toyota described by Liker and Convis.

Throughout my career as an internal “lean guy” in companies large and small, our “lean skill development” (or whatever you want to call it) process for leaders was largely driven by establishing requirements.

We wanted to require leaders to participate in kaizen events. We wanted to require them to attend the Lean 101 class. At one company, managers and supervisors were required to teach the “World Class Competitiveness” course. We want to include classes and educational events on their performance goals. We wanted to make them learn it.

To get back to an earlier post it doesn’t work.

The Toyota process is reversed. There is no requirement for anyone to master anything other than their current job. But if you want to get more responsibility, it is incumbent on you to demonstrate the drive to develop your own capability.

One purpose for universal team member involvement in kaizen is for leaders to directly observe who has the right motivation to learn and take on more. That is the beginning of the leadership development process.

In our companies today, of course, we have the situation of an existing hierarchy. Leaders have gotten into senior positions without having any of these skills. Our western management process is one of detached decision making from summaries presented by staff on PowerPoint. If a new initiative comes along, the senior leaders delegate it and “support” it by not shutting it down.

That doesn’t work if you want to change the status-quo.

What does? A drive to master something new and a realization that personal development is a continuous life-long process. That is the key message I get from this chapter. More to follow.