Sometimes I see people chasing their tails when trying to troubleshoot a process. This usually (though not always) follows a complaint or rejection of some kind.

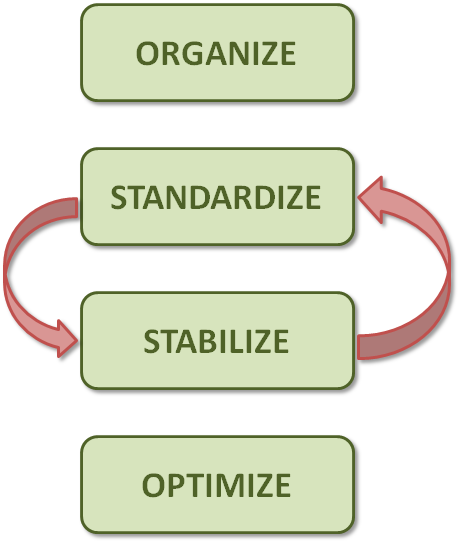

A few years ago I posted Organize, Standardize, Stabilize, Optimize and talked in general terms about the sequence of thinking that gives reliable outcomes.

This is a series of questions that, if asked and addressed in sequence, can help you troubleshoot a process. The idea is that you have to have a very clear “YES” to every question above before proceeding to the next.

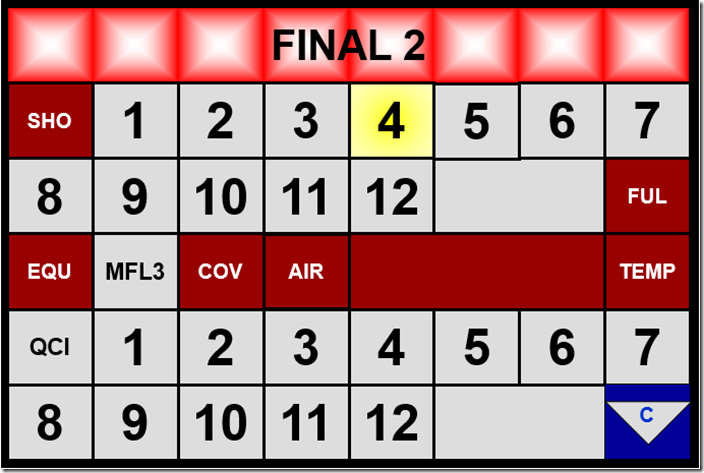

Question 1: Is there a clear standard for the outcome?

Why? Because if you don’t have a clear expectation of what “good” looks like then your definition of “not good” is subjective and varies depending on who, what, when things are being looked at.

If no, then define:

- What are you trying to accomplish from the customer’s perspective? What does “good” look like? How do you know?

- How does the team member performing the work know (and verify) that this expectation has been “met” or “not met” – each time.

- This includes not only the physical quality expectations but the required timing.

- What do you want the team member to do if she finds a problem? What is your process for escalation / response?

Question 2: Is there a clear standard for the method that will achieve the standard results?

Why? Because if you (as an organization) don’t know how to reliably achieve the standard you are relying on luck.

If no, then define:

- What steps must be performed, in what order, to get the outcome you expect?

- Content, Sequence, Timing to give the desired Outcome.

- How will the team member doing the work know (and verify to themselves) that the method was either “applied” or “not applied” according to your standard – each time?

- What do you want the team member to do is he can’t or didn’t carry out the process as defined? What is your process for escalation / response?

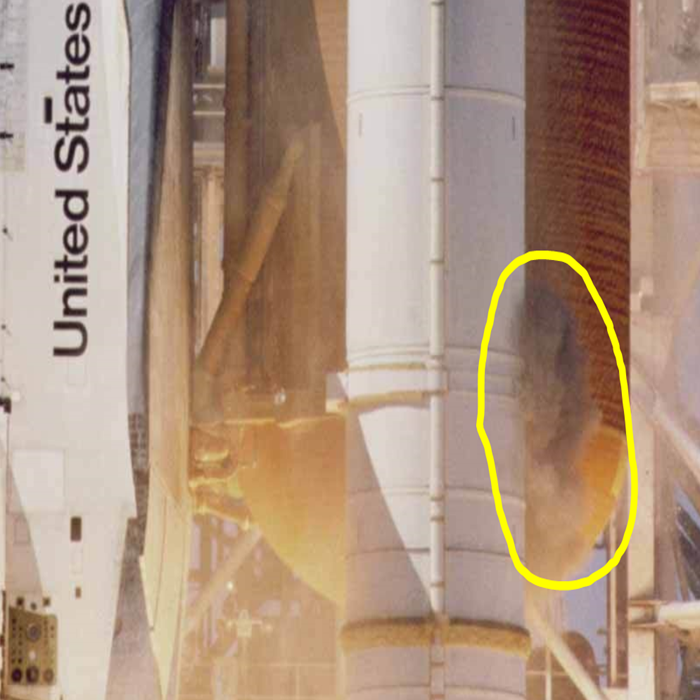

Question 3: Are the conditions required for success present?

Why? Because if the team member does not have the time, tools, materials, environment that are required to execute the process as designed they have to improvise and compromise.

If no, then define:

- What conditions must exist for your standard method to work?

- What conditions must exist to enable the team member to consistently execute to the standard with no work-arounds?

- How will you assure that the conditions exist prior to process execution each time?

- What stops the process from proceeding if the required conditions do not exist?

Question 4: Is there consistent execution of the standard method?

Why? If you have defined the method, and assured that the conditions required for success exist, then you must examine what other factors are causing process variation.

ACTIONS:

- CONFIRM the standard conditions exist. Correct or restore. Check for process stability.

- CHECK FOR other conditions which affect execution. Establish new standard conditions. Check for process stability.

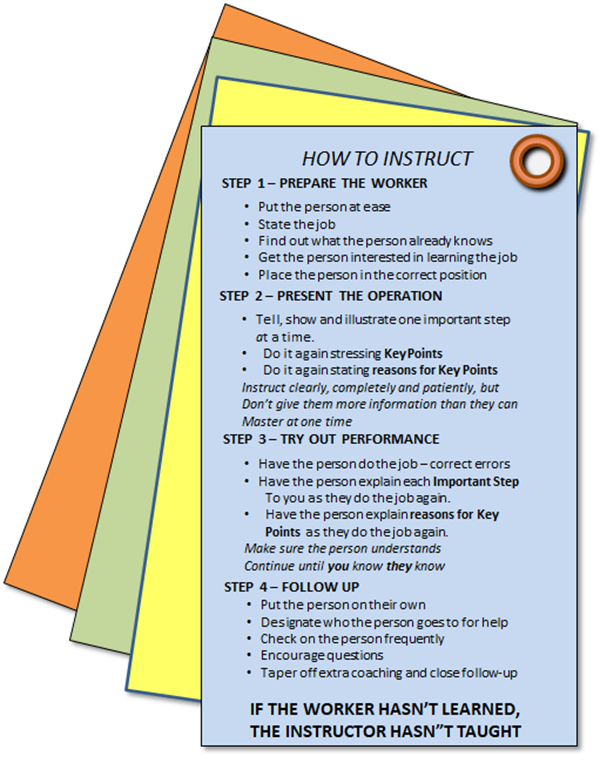

- CONFIRM clear understanding of the standard method. This would be a good time to engage TWI Job Instruction. Check for process stability.

- For all of the above – verify all suspect process output vs. the standard for outcome and results.

- If you discover an alternative work method that is clearly superior to the standard then Confirm, capture, verify. DEFINE a process for process improvement – how to alternatives get confirmed and incorporated vs. random mutations?

- Define your mistake-proofing / poka-yoke at the point where process execution varied to increase stability.

Question 5: Was a standard method followed and the results were as expected or predicted?

Why? After we have verified process stability, then we can ask “Does the process that we specified actually work as we predicted?

- REEXAMINE your standard method and conditions.

- Identify process failure points and sources of variation.

- Adjust the process to address those failure points and sources of variation.

- Repeat until your process is capable and consistently performs to the standard.

Question 6: Does everything work OK, but you want or need to do better?

Only a stable baseline can tell you how well you are performing today. Then you can assess if you need changes. If so, then reset your standard for expectations. Return to the top.

There are lots of classes and materials out there about “active listening” but I really like a simple techniques that

There are lots of classes and materials out there about “active listening” but I really like a simple techniques that  NO sarcasm. NO implied judgement. You must come from a position of being curious about what they are trying to communicate, and what they are feeling.

NO sarcasm. NO implied judgement. You must come from a position of being curious about what they are trying to communicate, and what they are feeling.