I just started reading this book, and my initial feeling is that it is a winner. Rather than producing a batch review of the whole thing at the end, I thought I would employ “one chapter flow” and share my impressions with you as they are formed. As I write this, I honestly do not know where it is ultimately going.

I am excited about this book because it is challenging the decades-old paradigm of kaizen events run by specialists (while simultaneously trying to justify the change activity to the people who hired them in the first place). In its place is a leader who knows what he is doing, and appears to be starting to lead by asking tough questions.

Even with that initial endorsement, this book appears to be following the standard formula established by Eli Goldratt in The Goal.

- Manager finds out factory is being closed. News is devastating to his personal life.

- The Jonah character emerges and teaches him how to save the operation.

- He applies what he learns and saves the day.

While there is nothing wrong with this structure, it is wearing a bit thin, at least to me. So I hope that the authors are going to find an interesting twist that surprises me. Still, because this is a novel with a point, vs. an attempt at classic literature, I’m not going to spend much time on the literary style.

The two main characters (so far) are Andrew Ward, the manager who finds out his plant is being closed, and Phil Jenkinson, the new CEO, with the double role of bringing the bad news (closing the plant) as well as filling the role of the Jonah (or sensei in this case, I suppose).

In the opening chapter, Jenkinson’s style is authoritative, bordering on confrontational. Without knowing the culture of this fictitious company, I can’t say whether his blunt, direct approach is from necessity or because he simply doesn’t have the skills to ask tough questions without pushing people back. I’ll hold judgment on that part. My hope is that the book doesn’t teach this approach as how it has to be done, because in my experience, it doesn’t have to work that way.

The message, though, is crystal clear. The old way isn’t cutting it. Leaders, not staff, are responsible for results (safety, quality, delivery, cost). Leaders are expected to know the hot spots in their operations. Leaders are expected to be involved in the details – not to micro manage, but to develop the capabilities of others. (That last one is a bit of an extrapolation on my part.) “Lean” is not a program, not projects run by a staff of specialists, it is how we will manage the company.

The notable quote from this chapter comes in a shop floor lecture given by Jenkensin and nicely sums up the relationship between process and results.

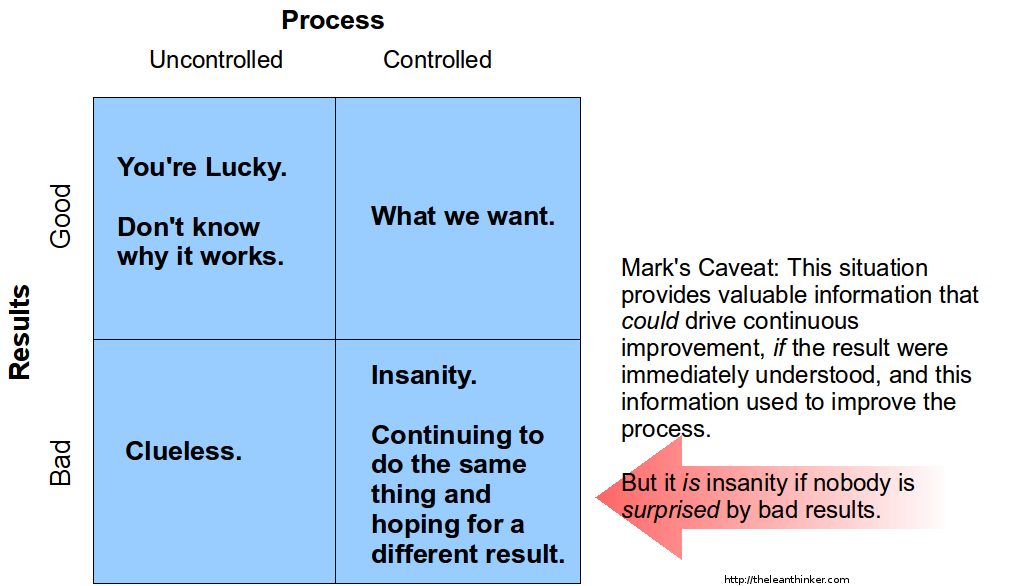

“Results… are the outcome of a process. What we want are good results from a controlled process because they will be repeatable. Bad results from an uncontrolled process simply mean that we’re not doing our job. Good results from an uncontrolled process…only mean we’re lucky. Today, bad results from a controlled process just says that we’re stupid: We expect different results from doing the same thing over again.”

Based on that, I sketched out this little matrix that captured my response and the key points.

But the technical nuances aside, this story is clearly developing into one about leadership. The key issues, so far, are:

- Safety, quality, delivery, cost, are line leaders’ responsiblity, with assistance from technical staff – who are also experts.

- Though it is certainly a culture shock, the leader is teaching by asking questions.

- The various character’s reaction to the confrontive authoritative style is predictable. I am uneasy, at this point, with that approach being held up as an example of the best way to get this done. But it is only Chapter 1.