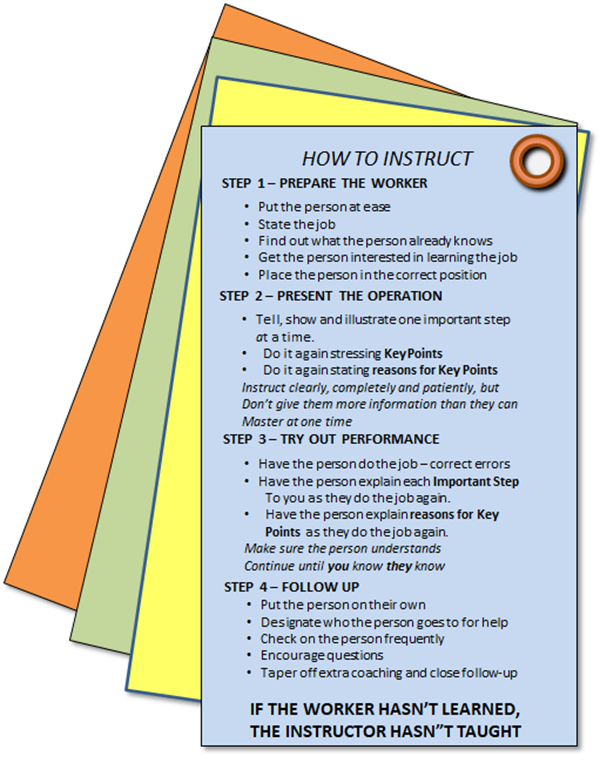

TWI Job Instruction is built around a four step process titled “How to Instruct.”

Steps 2 and 3 are the core of the process.

- Present the Operation

- Try Out Performance

I want to discuss Step 3: Try Out Performance

Teaching Back as Learning

All too often I see “training” that looks like this:

- Bring the team members into a room.

- Read through the new procedure – or maybe even show some PowerPoints of the procedure.

- Have them sign something that says they acknowledge they have been “trained.”

This places the burden of understanding upon the listener.

The TWI model reverses this paradigm with the mantra at the bottom of the pocket card which, though they vary from version to version, is some form of: If the student hasn’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught.

Having the learner teach back to the instructor does two things:

- The learner has to understand it better to be able to explain it.

- It provides a verification check that the instruction has been effective.

Point two is important here. Instruction is a hypothesis: “If I teach these steps, in this way, my learner will be able to perform the process.”

Having them teach back is the testable outcome of this hypothesis. If the the learner struggles, then the instructor must re-instruct. But not simply by rewinding the script and playing it again… we know that didn’t work. Instead the instructor now has to get curious about which points are confusing the learner and why, and correct his instruction.

But that’s not what I came here to discuss. TWI is just a lead-in.

Learning to See – by Practicing

An operations manager who is learning fast was challenging my insistence on having a visual status board that showed the real-time location of product on the line.

In the same breath, he was saying that he wanted the leads and the supervisor to be able to “walk the trapline” and do better seeing issues coming before a train wreck. (Empty positions, overproduction, etc.)

My response was “Having them update the magnets on that board every time something moves forces them to practice seeing what is where.”

In other words, by making them teach you where things are, and demonstrate their knowledge, they have to learn how to see that bigger picture.

“That’s the best explanation I have ever heard.”

The operations manager can walk the line and see the status himself. He doesn’t need the board. In fact, he could see even better if he went up the mezzanine overlooking the line. It’s all there.

But the board isn’t for his benefit. It is a learning tool. It is structure for the leads and supervisors to have a joint conversation, facing the board instead of each other, and reach agreement about what is where.

It gives them a clear indication if they need to escalate a problem, and a way to be able to converse about when and how they might recover (or not).

In other words, it is “Grasp the Current Condition” continuously, in real time. This lets them compare the current condition with the target condition – the standard depicted on the board.

By seeing gaps quickly, they have a better chance at seeing what obstacle or problem prevented them from operating to the target.

That, in turn, gives the manager an opportunity – in invitation – to shape the conversation into one about improvement.

Back to Job Instruction

This is exactly the same process structure as having the learner demonstrate performance. It is a check, right after the operation (present the operation) was performed to see how well it worked.

Fine Grained Observation

All of this is about moving observations, evaluations, checks, verifications away from batching them at the end of a huge block of work and embedding them into one-by-one flow. It builds Ohno’s “chalk circle” into the work itself.