A long, long time ago – in the days when computer programs were coded as holes in punch cards – I was in ROTC* in college. Twice a year we had a “PT” (Physical Training, I think) test that consisted of measured performance on five “events.” One of those events was a 2 mile run. To get a maximum score of 100 points, the participant had to complete the 2 mile run in 14 minutes and 9 seconds. Why? I have no idea. But that was the way it was.

My buddy John and I enjoyed running, and would often work out together. Our school was in Potsdam, New York, a place known for rather brutal winters, so we ran on a 1/10 mile indoor track.

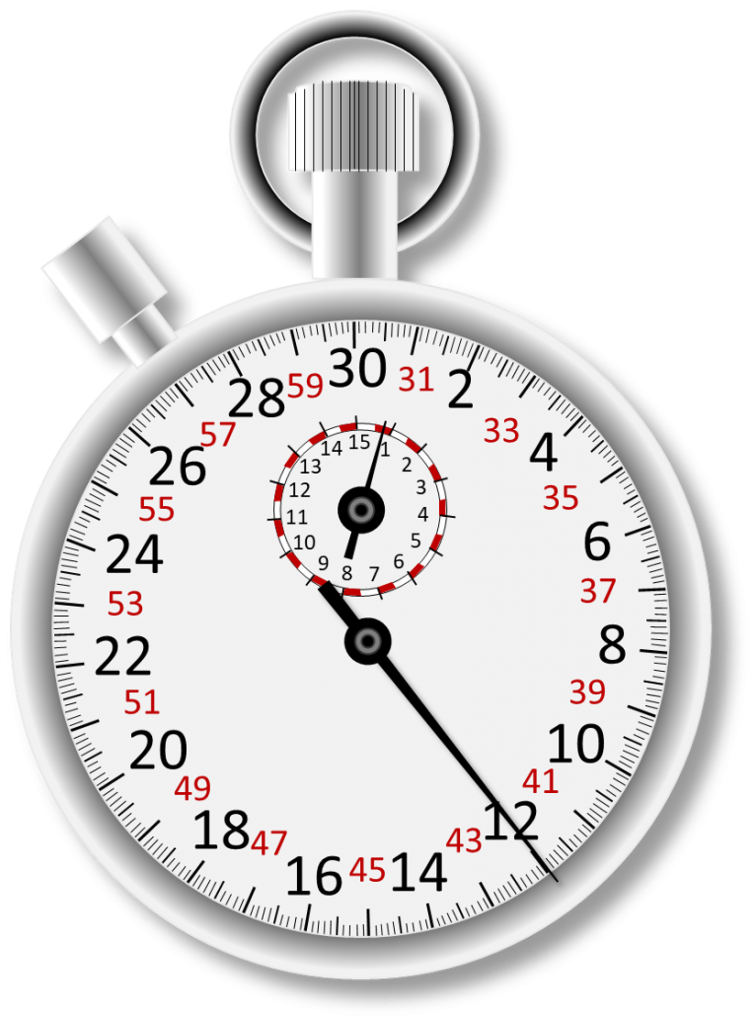

We practiced the PT test. John would track our total time for 2 miles (20 laps around the 1/10 mile track). I would measure lap times. Since 14 minutes is 840 seconds, we knew that if we could consistently make 42 second laps, we would complete two miles in 14 minutes, and get the maximum score with 9 seconds to spare.

The track had hash marks at each quarter point, so we knew we had to hit quarter 1 between 10 and 11 seconds, half way at 21, the 3/4 mark between 31 and 32, and the lap at 42. We would check and adjust our pace accordingly, striving to hit exact 42 second laps every time.

To be clear, we could hold that pace many times further than 2 miles. It wasn’t a matter of conditioning. We weren’t going all out. We were going fast enough. And that was the point.

When we took the test, other cadets were going all out, passing us, and turning in much faster times. Others would try to “pace themselves” and then sprint as fast as they could for that last lap. As a general rule, although the instructors were calling out elapsed times as people went by, these cadets weren’t all that aware of the speed they had to hold. They were just going as fast as they could.

Meanwhile, John and I, running together, and tracking our cycle times (lap times) vs the takt time (42 seconds / lap) would come in at pretty much exactly 14 minutes and get the same score as everyone who had finished ahead of us: 100 points.

After our timed run was done, we would keep running, offering encouragement and pacing for those cadets who were struggling a bit. Everyone finishes, nobody left behind.

A couple of the instructors were curious why we didn’t go for a faster time. And many times we did when we were just working out. We were capable of breaking 12 minutes – not competitive times in a track meet, but respectable. The simple fact was that going faster wasn’t necessary to accomplish the goal.

Takt Time and Cycle Time

This is the whole point of having a takt time. It answers the question, “How fast must we go?” It doesn’t answer “How fast can we go?” nor does it answer “How fast should we go?” I fact, John and I could have run those laps almost (but not quite) half a second slower than we did – which would have eaten into the 9 second buffer we established. Aside from making the math easier, that buffer also gave us a small margin for even something as bad as taking a stumble and standing back up. Also, of course, we could make up 5-10 seconds a lap if we really had to. But we never did. Time: 14:00. We were very consistent.

Rate vs. Output

I encounter a lot of production managers who are so conditioned to focus on the daily output that they don’t even think about the critical factor: How fast are you running vs. how fast do you need to run? In other words what is your rate of output vs. your takt time?

Instead they tend to, at best, count units of output without really paying attention to the time interval between one and the next. In the worst case many units are started at once, and people swarm from one operation to the next during the day – the equivalent of that mad sprint trying to make up as much time as possible. They don’t really know if they will succeed or not until the end of the day (or month!).

It Isn’t a Race

The “just” in “just-in-time” is “just enough resources” to “just make the output you need” in any given time interval. As the operation is streamlined, the same effort is able to accomplish more. Where to put that additional capacity (which costs nothing additional since it has been there all along) to create more value should be the challenge the organization is trying to meet.

My experience has been that managers and leaders often struggle to adopt this “rate” mindset and let go of chasing an inventory number. In the words of the late great philosopher Kenny Rogers – “There’ll be plenty of time for counting when the dealings done.”

*ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Corps) is a U.S. program where college students can earn a commission in the U.S. Armed Forces while earning their degree.