I am taking the Toyota Kata seminar this week in Ann Arbor. There are two programs offered:

- A one-day classroom overview of the concepts in Toyota Kata.

- The one-day classroom overview followed by two days of practice on a shop floor, for a total of three days.

I am taking the three day version.

Impressions of Day 1

There are about (quick count) 36 participants, a big bigger group than I expected considering the premise. I don’t know how many are not going to be attending the shop floor part, but most people are.

I suppose the ultimate irony is the slide that makes the point that classroom training doesn’t work very well for this.

Realistically, I can see it as necessary to level-up everyone on the concepts. The audience runs the gamut of people who have read, studied, written about, made training material from, and applied the concepts in the book; to people who seem to have gone to the class with quite a bit less initial information.

That being said, everyone had some kind of exposure to lean principles, though there was a lot of “look for waste” and “apply the tools” mindset present. Since one of the purposes of the class is to challenge that mindset, this is to be expected.

You can get a good feel for the flow and content of the material itself on Mike Rother’s web site. He has a lot of presentations up there (via Slide Share).

Like any course like this, the more you know when you arrive, the more nuance you can pull out of the discussion.

Since I have been trying to apply the concepts already, my personal struggles really helped me to get a couple of “ah-ha” moments from the instruction.I arrived with a clear idea of what I wanted to learn, and what I thought I already knew. Both pre-disposed me to get insight, affirmation, and surprise learning from the material.

I would not suggest this for anyone who was looking to be convinced. Classroom training in any case doesn’t do that very well, and this material isn’t going to win over a skeptic. You have to be disposed to want to learn to do it.

At the end of the day, the overall quality, etc. of the presentation was pretty typical of “corporate training” stuff – not especially riveting, but certainly interesting. But we don’t do this for the entertainment value, and the learner has a responsibility to pull out what they need in any case.

Insights from Day 2

Day 1 is intended, and sold, as a stand-alone. The next two days are available as follow-on, but not separately.

The intended purpose was to practice the “improvement kata” cycle in a live shop floor environment. Today was spent:

- Developing our “grasp of the current condition.” There is actually a quite well structured process for doing this fairly quickly, while still getting the information absolutely necessary to decide what the next appropriate target is.

- Developing a target condition. Based on what we learned, where can this process be in terms its key characteristics and how it performs, in a short-term time frame. (A week in this case)

Key Points that are becoming more tangible for me:

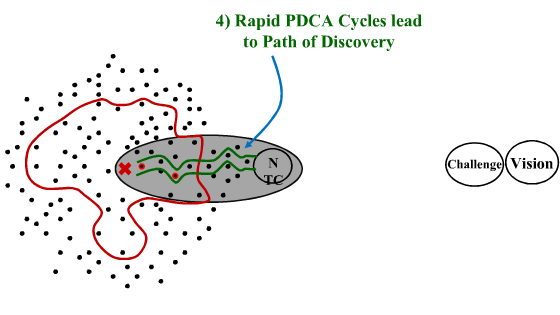

The “Threshold of Knowledge” concept.

I elaborated on Bill Costantino’s (spelled it right this time) presentation on this concept a while ago. In the seminar, I am “groking” the concept of threshold of knowledge a bit better. Here is my current interpretation.

There are really three thresholds of knowledge in play, maybe more. First is the overall organization. I would define the organizations’ threshold of knowledge as the things they “just do” without giving it any thought at all.

For example – one company I know well has embedded 3P into their product design process to deeply that the two are indistinguishable from one another. It is just how they do it.

They still push the boundaries of what they accomplish with the process, but the process itself is familiar territory to them.

Likewise, this company has a signature way to lay out an assembly line, and that way is increasingly reflected in their product designs as 3P drives both.

It wasn’t always like that. It started with a handful of people who had experience with the process. They guided teams through applying it, in small steps, on successively more complex applications until they hijacked a design project and essentially redid it, and came out with something much better.

Another level of knowledge threshold is that held by the experienced practitioner.

Today I walked into a work cell in the host company for the first time, and within a few minutes of observation had a very clear picture in my own mind of what the next step was, and how to get there. My personal struggle today was not in understanding this, but in methodically applying the process being taught to get there. I knew what the answer would be, but I wasn’t here to learn that.

An extended threshold of knowledge in one person, or even in a handful of people, is not that useful to the company.

But that is exactly the model most kaizen leaders apply. They use their expert knowledge to see the target themselves, and then direct the team to apply the “lean tools” to get there.

They tell the team to “look for waste” but, in reality, they are pushing the mechanics. You can see this in their targets when they describe the mechanics as the target condition.

The team learns the mechanics of the tools, but the knowledge of why that target was set remains locked up in the head of the staff person who created it.

So his job is to set another target condition: Expanding the threshold of knowledge of the team.

He succeeds when the team develops a viable target themselves. It might be the same one he had, but it might not. If he framed the challenge correctly, and coached them correctly, they will arrive at something he believes is a good solution. If they don’t he needs to look in the mirror.

So the next level of knowledge threshold is that held by the team itself.

If enough teams develop the same depth, then they start to interconnect and work together, and we begin to advance the organization’s threshold. Now what was previously required a major “improvement event” to develop is just the starting baseline, and the ratchet goes up a bit.

None of the above was explicitly covered today, but it is what I learned. I am sure I’ll get an email from a certain .edu domain if I am off base here.

There is no Dogma in Tools

This is the third explicit approach I have been taught to do this.

The first was called a “Scan and Plan” that I learned back in the mid/late 1990’s. It was more of a consultant’s tool for selecting a high-potential area for that first “Look what this can do” improvement event.

Though I don’t use any of those forms and tools explicitly, I do carry some of the concepts along and apply them when appropriate.

Then I was exposed to Shingijutsu’s approach. This is heavily focused on the standard work forms and tools. Within the culture of Shingijutsu clients, it would be heresy not to use these forms.

The “Kata” approach targets pretty much the same information, but collects and organizes it differently. I can see, for myself, a of better focus on the structure of establishing a good target. I can also see a hybrid between this method and what I have used in the past. Each form or analytical tool has a place where it provides insight for the team.

One thing I do like about the “Kata” data collection is the emphasis on (and therefore acknowledgement of) variation in work cycles. (All of this is in the book by the way. Read it, then get in touch with me if you want some explanation.)

Now, I want to be clear – in spite of the title of this section, when I am coaching beginners, I will be dogmatic about the tools they use. In fact, I plan to be a lot more dogmatic than I have been.

I am seeing the benefit of providing structure so that is off the table. They don’t have to think about how to collect and organize the data, just getting it and understanding it.

What I can do, as someone with a bit more experience, is give them a specific tool that will give them the insight they need. That is where I say “no dogma.” That only applies when the principles are well within your threshold of knowledge.

The real ah-ha is that, unlike the Shingijutsu approach, we weren’t collecting cycle times at the detailed work breakdown level. Why not? Because, at this stage of improvement, at this stage of knowledge threshold for the team, the work cell, that level of detail is not yet necessary to see the next step.

I will become necessary, it just isn’t necessary now.

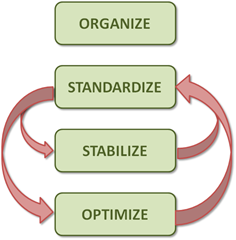

Target Conditions and PDCA Cycles

One place where my work team bogged down a bit this afternoon was mixing up the target condition that we are setting for a week from now, and what we are going to try first thing in the morning.

The target condition ultimately requires setting up a fairly rigid standard-work-in-process (SWIP) (sometimes called “standard in-process stock) level in the work cell.

There was some concern that trying that would break things. And it will. For sure. We have to stabilize the downstream operation first, get it working to one-by-one, and make sure it is capable of doing so.

The last thing we want to do while messing with them is to starve them of material.

So – key learning point – be explicitly clear, more than once, that the Target Condition is not what you are trying right away. It is the predicted, attainable, result of a series of PDCA steps – single factor experiments. You don’t have the answers of how to do it yet. So don’t worry about the SWIP level right now. That will become easier… when it is easier.

More tomorrow…