Jeff asked an interesting question in a comment to the post Often Skipped: Understand the Challenge and Direction:

[Hoshin Kanri] seems to suggest I reach long term objectives (vision) through short term initiatives/projects as if I can (should?) know the steps. [Toyota Kata] says I don’t know the way to reach my long term vision, so I limit focus to next target condition and experiment (repeatedly) toward the vision.

Seems contradictory to me. What am I missing?

Let’s start out with digging into what hoshin kanri is supposed to do. I say “supposed to do” because there are a lot of activities that are called “hoshin kanri” that are really just performance objectives or wish lists.

First, hoshin kanri is a Japanese term for a Japanese-developed process. We westerners need to understand that Japanese culture generally places a high value on harmony and harmonious action. Where many Americans (I can’t speak for Europeans as well) may well be comfortable with constant advocacy and debate about what should be worked on, that kind of discussion can be unsettling for a Japanese management team.

Thus, I believe the original purpose of hoshin kanri was to provide a mechanism for reaching consensus and alignment within a large, complex organization.

In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, hoshin kanri concepts emerged out of their Japanese incubator and came to western business. In this process, the DNA combined and merged with western management practices, and in many (never say “all”) western interpretations, the hoshin plan tends to be something patched onto the existing Management By Objectives framework.

That, in and of itself, isn’t a bad thing. Hoshin kanri’s origins are from MBO migrating to Japan where they took MBO and mixed in Japanese cultural DNA.

However, I’m not comfortable that what we have ended up with in the west meets the original concept or intent.

With that as background, let’s get to the core of Jeff’s question.

What is the purpose of hoshin kanri?

Let’s start with chaos. “We want continuous improvement.”

In other words, “go find stuff to improve,” and maybe report back on what you are going to work on. A lot of organizations do something like this. They provide general guidance (if they even do that), and then maybe have the sub-organization come tell and report what they expect to accomplish. I have experienced this first hand.

“I expect my people to be working on continuous improvement,” says the executive from behind his desk in the corner office. Since he has delegated the task, his job is to “support his empowered workforce” to make things better.

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a

continuous conversation and stream of consciousness within the organization. That is very rare. How to achieve that alignment is the problem hoshin kanri is intended to solve. It isn’t the only way to do it, but it is an effective method.*

A Superficial Overview of the Process of Hoshin Kanri

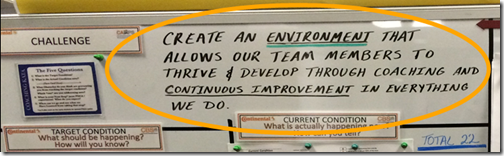

The leadership sees or sets a challenge for the organization – something they must be able to do that, today, they cannot. This is not (in my opinion) the same as “creating a crisis.” A crisis just scares people. Fear is not a good motivator for creative improvement.

Different parts of the organization may get a piece of the challenge, or the leadership team may, as a whole, work to figure out what they need to accomplish. Here is an important distinction: “What must be accomplished” is not the same as a plan to accomplish it. A challenge, by its very nature, means “We don’t know exactly what we will have to do to get there.”

This can take the form of KPI targets, but that is not what you are doing if there is a simple percent improvement expected with no over-arching rationale.

Now comes the catchball.

Catchball is not Negotiation of the Goal

Catchball is often interpreted as negotiating the goals. That’s not it. The goals are established by a market or competitive or other compelling need. So it isn’t “We need to improve yield by 7%.” followed by “Well, reasonably, I can only give you 5%.” It doesn’t work like that.

Nor is it “You need to improve your yield by 7%, and if you don’t get it then no bonus for you.” That approach is well known to drive some unproductive or ineffective behavior.

And it isn’t “You’re going to improve your yield by 7% and this is what you are going to do to get there.”

Instead, the conversation might sound something like “We need to improve our yield by 7% to enable our expected market growth. Please study your processes as they relate to yield, and come back and let me know what you think you need to work on as the first major step in that direction.”

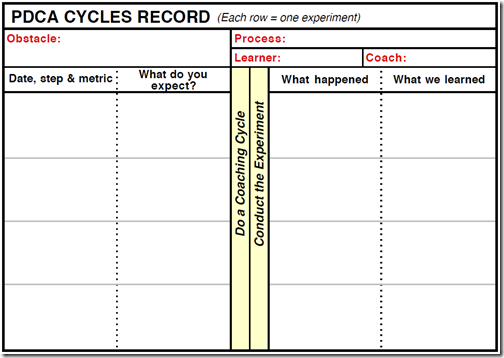

In other words, please grasp your current condition, and come back with your next target condition.

That sounds a lot like the Coaching Kata to me.

SIDEBAR:

Toyota Kata is not a problem solving method.

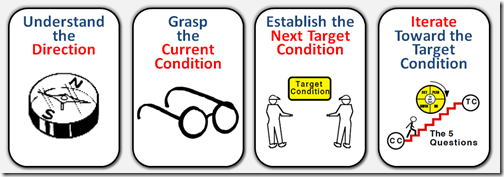

Toyota Kata is a set of practice routines designed to help you learn the thinking pattern that enables an organization to do hoshin kanri, and any other type of systematic improvement that is navigating through “We want to get there, but aren’t sure exactly how.”

An executive I am working with mentioned today that Toyota Kata is what is informing their policy deployment process. Without that foundation of thinking, their policy deployment would have been an exercise in assigning action items and negotiating the goals.

So what is the difference between hoshin kanri and Toyota Kata?

There isn’t a difference. They are two parts of the same thing. Hoshin kanri is a mechanism for aligning the organization’s efforts to focus on a challenge (or a few challenges).

Toyota Kata is a practice routine for learning the thinking pattern that makes hoshin kanri (or policy deployment) function as intended.

In hoshin planning, you are planning the destination, and perhaps breaking down individual efforts to get there, but nothing says you already know how to get there.

It isn’t an “action plan” and it isn’t a list of discrete, known action items. Rather, it is specific about what you must accomplish, and if you accomplish those things, then the results are predicted to add up to what you need.

What to Do vs How to Get It Done

At some point, someone has to figure out how to make the process do what is required. That has to happen down at the interface between people and the work actually being done. It can’t be mandated from above. Hoshin helps to align the efforts of improving the work with the improvements required to meet the organization’s challenge.

From the other side, the Improvement Kata is not about short-term objectives. The first step is “understand the challenge and direction.” Part of the coach’s job is to make sure this understanding takes place, and to ensure that the short-term target condition is moving in the direction of the challenge.

We set shorter term target conditions so we aren’t overwhelmed trying to fix everything at once, and to have a stable anchor for the next step. It enables safer learning by limiting the impact of learning that something didn’t work.

However, in Toyota Kata, while we might not know exactly how to get there, but we are absolutely clear where we have to end up.

The American Football analogy works well here. The challenge is “Score a touchdown.” But if you tried to score a touchdown on every play, you would likely lose the game. The target condition is akin to “get a first down.” You are absolutely clear what direction you have to move the ball, and absolutely clear where you need to end up in order to score. But you aren’t clear about the precise steps that are going to get you there. You have to figure that out as you go.

Hoshin Kanri focuses the effort – “What to work on.”

Toyota Kata teaches the thinking behind “How to work on it.”

*Though hoshin kanri may be effective, getting it to work effectively is a journey of learning that requires perseverance. It is much more than filling out a set of forms.

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a