Emily sent an email asking “how would you describe the difference between GOAL and TARGET CONDITION?”

I end up on this topic enough that I thought I’d discuss it here.

I am assuming we are referring to the “Toyota / Toyota Kata” context here. I mention that because while “target condition” has a pretty clear meaning in that context, we have to rely on the everyday meaning definition for “goal.”

Thus, I can’t objectively say “goal” means this, or doesn’t mean that because it means whatever it means to you.

Still, I can give it a try.

I have drawn on the following analogy frequently because I think it demonstrates the concept pretty well.

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

I’d say that was a goal. It is a specific accomplishment that is clearly “done” or “not done” and it has a deadline. (Someone else once said “a goal is a dream with a deadline.”)

For those of you who don’t remember Woodstock*, let me provide some context.

President Kennedy made that speech on May 25, 1961.

On May 5th, Alan Shepard had been launched into a sub-orbital space flight giving the USA a total manned space flight experience base of about 15 minutes. The previous month, the Soviet Union had launched Yuri Gagarin for a single orbit around the Earth, thus the entire planet had a total manned space flight experience of just under 2 hours (but the Russians weren’t sharing).

On May 5th, Alan Shepard had been launched into a sub-orbital space flight giving the USA a total manned space flight experience base of about 15 minutes. The previous month, the Soviet Union had launched Yuri Gagarin for a single orbit around the Earth, thus the entire planet had a total manned space flight experience of just under 2 hours (but the Russians weren’t sharing).

<— This is the best we could do.

The goal was selected for political and technical reasons. We had developed a huge rocket engine needed to do the job, and didn’t think the Russians larger rockets would scale well. So the Administration selected a goal they thought the U.S. could accomplish but believed the USSR would have a tougher time with. (They were right.)

At the time the speech was made, there were two competing approaches in play for landing a man on the moon.

Both involved landing a large upper stage intact on the moon, then lifting off and using the whole thing to return to Earth.

The problem was thought to be how to get that huge moon landing rocket off the Earth and to the moon.

There were a couple of ideas kicking around at the time.

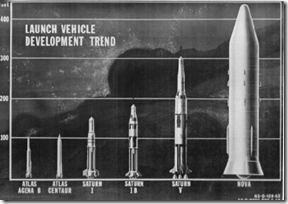

One was to build a huge rocket, maybe twice the size of the Saturn-V that eventually was used for Apollo 11.

The design was never finalized, but the concepts were all lumped together as the “Nova” rocket. You can see the 36 story tall Saturn V (the biggest rocket ever built and launched) as the second from the right in this picture. The idea was to send the entire thing directly to the Moon with a single launch. This was called the “Direct” approach.

The design was never finalized, but the concepts were all lumped together as the “Nova” rocket. You can see the 36 story tall Saturn V (the biggest rocket ever built and launched) as the second from the right in this picture. The idea was to send the entire thing directly to the Moon with a single launch. This was called the “Direct” approach.

Given that building the Nova rocket (not to mention the launch facility) was likely to be…um…really hard, the other idea was to use multiple launches of something more like the Saturn rocket, and assemble the moon rocket in low Earth orbit, then send it on its way. This was called “Earth Orbit Rendezvous.

All through the late spring and summer of 1961 this debate was raging within NASA. Wernher von Braun, our chief “rocket guy” wanted this capability for a large lunar payload because he was interested in establishing bases and serious exploration of the moon. But that wasn’t the objective right now. It was get there fast and beat the Russians.

Another NASA engineer, John Houbolt had what was considered a bit of a high-risk (bordering on crackpot) scheme of a smaller-but-still-huge rocket, single launch, sending an expendable two-stage lander to the moon, having it land with two astronauts, then lift off and rendezvous with the return ship in lunar orbit. Not surprisingly this scheme was known as “Lunar Orbit Rendezvous.” It was risky because what was thought to be the trickiest part, the rendezvous and docking, was to be done 250,000 miles from the safety of Earth, with no way home if it didn’t work.

You can read the whole story here.

By the fall of 1962, Lunar Orbit Rendezvous had emerged as the only viable scheme to accomplish the goal by the deadline.

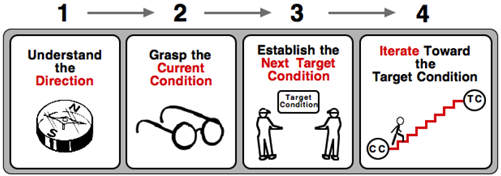

At the program level, they now had a target condition: How the process should operate in order to accomplish the goal. This does not mean they had worked out every detail. It only means they knew what they were trying to accomplish. This 1962 NASA film pretty much lays out the concept in as much detail as they understood at the time:

Remember, this is at the high level. But at this level they identified obstacles – things they didn’t know how to do – that had to be cleared in order to reach the target condition.

1) They had to develop the concept into a real rocket capable of pushing 90,000 pounds (and finally 100,000 pounds) into lunar orbit. They also had to develop and built the infrastructure to (according to the initial plan) launch one of these every month.

2) They had to determine if (and how) humans could spend 10+ days in space without psychological or psysiological problems. (Remember, we had no idea at the time).

3) They had to develop a space suit that would allow an astronaut to leave the spacecraft.

4) They had to develop techniques and technology for rendezvous and docking in orbit.

Each of these major obstacles could be, in turn, defined as a goal (or challenge) for the next level down. Project Gemini’s purpose was to test #2, and directly learn about #1 and #2.

And of course, the teams working on developing space suits, developing docking technology, etc. then would set their own target conditions that progressively marched toward their goals or deliverables.

Bring this back to Earth

A goal is something you need to accomplish. It usually doesn’t assign the method, only the result and the “by when.”

A target condition is typically a major intermediate step toward the ultimate challenge. Importantly, it outlines the “how” or proposed approach, though necessarily doesn’t offer up the solutions to the problems.

The goal is “win the game.” The target condition is the game plan. To execute the game plan, we need to develop specific capabilities, or solve specific problems.

One thing the target condition does do is limit the domain of the problems that must be solved. This is critical.

There are always more problems to solve than are solvable with the resources available. By being specific about a target condition, you focus the effort on the obstacles that are actually in the way of achieving the target. As you proceed, you learn, and as you learn, the nature of those obstacles may change. Thus, the obstacles are not a static list of things to do. Rather, they are the unsolved issues that, right now, you think must be dealt with.

See this (largely redundant) post from a couple of years ago for another perspective. (oops – just realized I’d already used the Apollo analogy. Oh well. At the time all of this was going on, I was the geeky 12 year old who knew (and would talk endlessly about) every dimension, rocket engine nomenclature, fuel burn rates, etc. of the Saturn-V rocket.)

Hopefully this will spark some discussion.

———–

*If you actually remember being at Woodstock, then you likely weren’t there. ![]()