My intent with this post is to spark a conversation about whether it is time to adjust what we teach people to say when they are teaching TWI Job Relations. It is based on, and expanded from, a talk I gave at the 2023 TWI Summit.

Background

TWI stands for Training Within Industry, a program developed during WWII by the U.S. War Manpower Commission. During the war there was huge growth and turnover within the industrial base as production shifted from civilian products (locomotives, for example) to wartime production (tanks). Many of the (mostly male) workers were drafted or enlisted. People with no industrial experience were joining the workforce. Technicians, often very technically skilled, but inexperienced in leading people, were put into supervisory positions.

The Commission deployed a series of training programs to teach industrial supervisors:

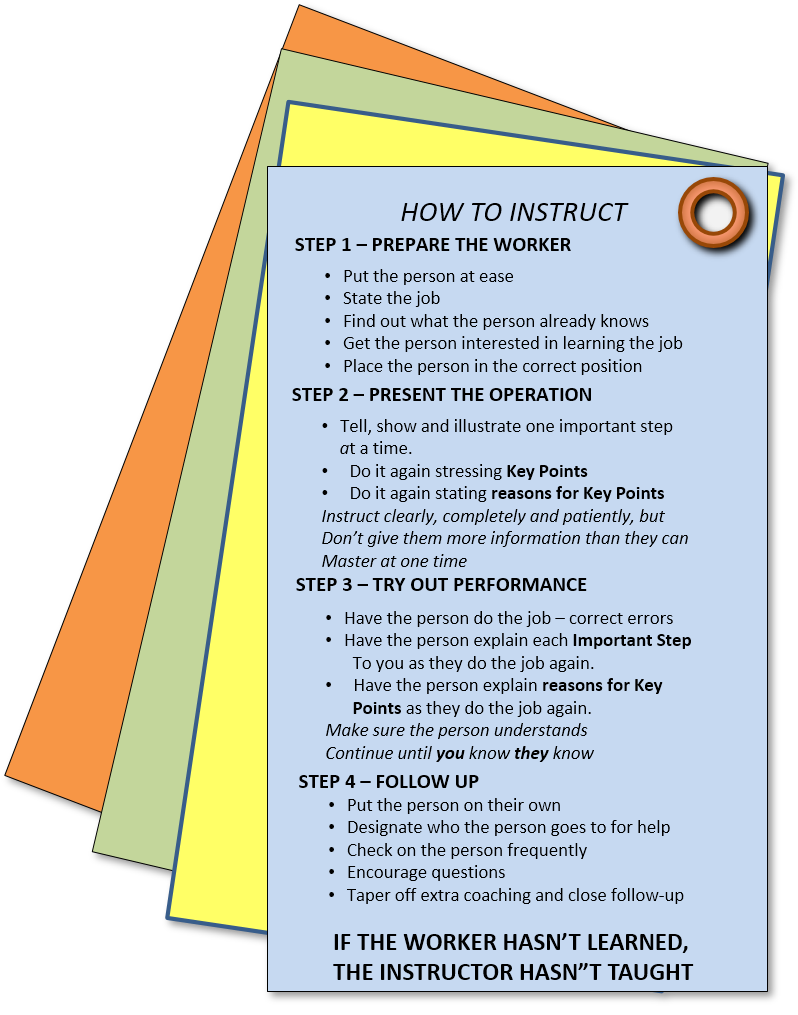

- Job Instruction, teaching the skill of breaking down a job and teaching it to others.

- Job Methods, teaching the skill of analyzing work with an eye to improve efficiency.

- And, Job Relations, what we are discussing here, the skill of handling people problems.

The program produced detailed manuals for certified instructors, and was rigorous in insisting that instructors not deviate from the words in the manual (unless the manual called out using their own words to tell a story, for example).

Today there are a lot of people, both internal trainers and quite a few outside training companies and consultants, using this material to teach.

In many cases the material these current-day trainers use deviates very little from the source material.

In addition, there are companies that are “training the trainer” to deliver the course precisely – which is good – and coaching them not to deviate from the words in the manual.

When we have people follow a script, they are playing a role that is defined by the voice in the script. Yes, they bring their own style, but the scripted dialog sets the tone of the message.

I believe it is time to take a look at that source material through the lens of 21st century values and ask whether or not we should revise the words and content in that script rather than blindly following something written in 1944 as though it is somehow sacrosanct. If the words do not match the story we want to tell, and the values we want to communicate, then perhaps we should update the script.

The challenge, of course, is that nobody owns this material. The original 1944 manuals are all in the public domain. Thus there is no central owner or go-to “keeper of the configuration.” Anyone can take the source material, and with some practice and feedback, do a credible job delivering it. But it remains that most of the versions in use out there don’t deviate much from the original material.

Thus, my message is not about anyone in particular. It is about the 1944 material. What follows is a review I would write if it were just being published, separating from the legacy and taking an objective look at the document and training material as it stands on its own.

If you are considering using it yourself, or are considering hiring someone to bring this material to your company, then hopefully this will make you a better customer by arming you with some questions to ask.

Determine Objective: What Kind of Relations Do We Want?

The TWI Job Relations course emphasizes the importance of supervisors having “good relations” with their people, and giving supervisors the basic skills they need to develop and maintain those relations is clearly the objective of the course. In principle, I agree with this objective 100%. The relationships between a supervisor and the team are critical to the success of the organization.

How do we define “Good” in “Good Relations?”

If “good relations” is the overall objective, then we should look at what is meant by the word “good.” I think the answer depends on the person’s mental model and biases about the role of authority. There are a couple of distinct paradigms I want to discuss. There may be more, but I think most are variations of these two. And, to be clear, this is actually a continuum rather than a bipolar model. I am just showing the endpoints.

Thus, rather than thinking about whether a particular turn of phrase in the script represents one end or the other, perhaps ask, “Which direction is it nudging things?” In other words, which end of the continuum is it biased toward – and is that the direction you want to emphasize in your own organization?

Traditional Transactional Relationships

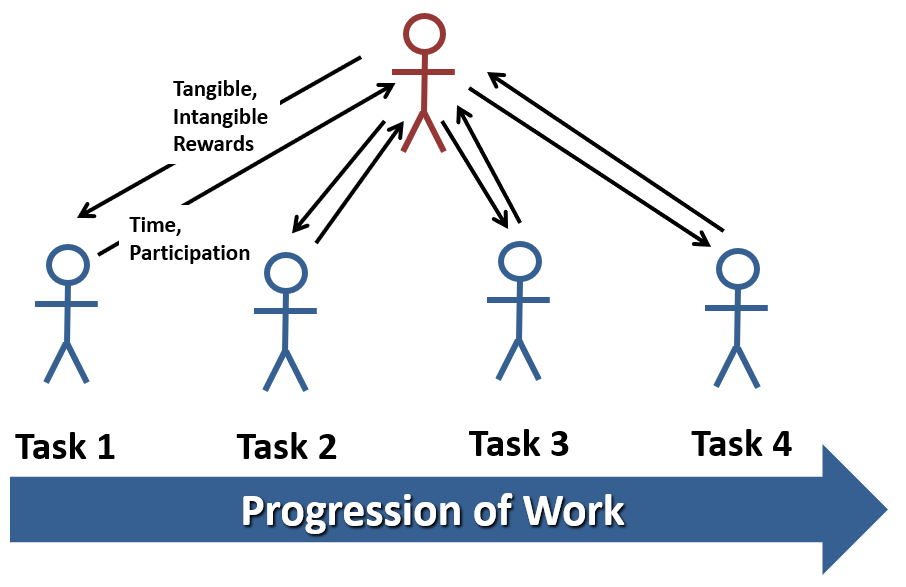

In a lot (probably most) organizations the relationship between the supervisor or boss and their subordinates is largely transactional.

They ask people to give their time and participation in exchange for tangible benefits (like pay) and intangible rewards (like approval).

This model embeds some tacit assumptions including:

- If everyone does their job, we get the result we want.

- The supervisor is largely responsible to define the jobs.

- The supervisor is responsible ensure that everyone is doing those jobs.

The Job Relations material is pretty explicit when it describes the purpose of the class:

Management wants output and quality.

Output and quality always require the loyalty and cooperation of the people in addition to what machines can accomplish.

Can we do something which will improve loyalty and cooperation? That is the purpose of these meetings.

– From Job Relations Session 1

Loyalty and cooperation are certainly things we would like to get from people, but I also think it is also a pretty low bar. And loyalty is a two-way street, at least outside of a dysfunctional relationship where it is expected but not given outside of the bounds of a transaction.

A Mechanistic Model of the Universe

This transactional view is representative of a 17th century mindset that, unfortunately, prevails today in many domains, especially in business and industry.

Largely defined in the work of René Descartes (1596-1650) and really solidified in the work of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) this model depicts a universe that operates like clockwork. It is mechanistic. It is deterministic – if we know the starting positions and characteristics of the pieces, we can predict what will happen. This is a reductionist view – we can understand the whole by decomposing it and understanding the parts. If we optimize the parts, we will optimize the whole.

From the 1944 perspective, the world of physics had been grappling with the idea that none of this is actually true for the previous 30 years or so. In the world of everyday experience, the mechanistic view still made common sense to people. It still does today. But on the level of human relationships, we now understand things much better.

The Mechanistic View in Industry

What do I observe that might lead me to conclude that the mechanistic view prevails in a business or factory?

Relationships Are Transactional

There are discussions around the relationship as an exchange between the business and the employee.

Motivation is Regarded as Extrinsic

“They are only here for the paycheck” and even the attitude that the purpose of treating people well is to motivate them to perform – as part of the transaction. The general belief here is that if it were not for the external rewards, people would not bring what is required to the job.

Issues, “problems,” are framed as restoring or renegotiating the transactional relationship, or at best, heading off things that might disrupt it.

The Goal or Objective is for everyone to “do their part” for the performance of production – to meet the needs of the organization which is thought of as separate from the employees.

Therefore, leaders intercede when something threatens production. Their goal, their objective, is to head off threats to the status-quo or to restore the status quo.

Now, to be clear, there are elements of these things in even the most enlightened organizations. But there are key differences in the underlying paradigm and, more critically, the words that are used when discussing problems.

The Holistic, Teamwork View

The reductionist, mechanistic model is appealing because it creates an illusion of direct cause-and-effect between a change in one component and the overall outcome. It is also appealing because it gives the illusion that we can deal with each component, including each person, separately, and shape their behavior by altering the terms of the transaction.

We have learned a lot since the early 1940s.

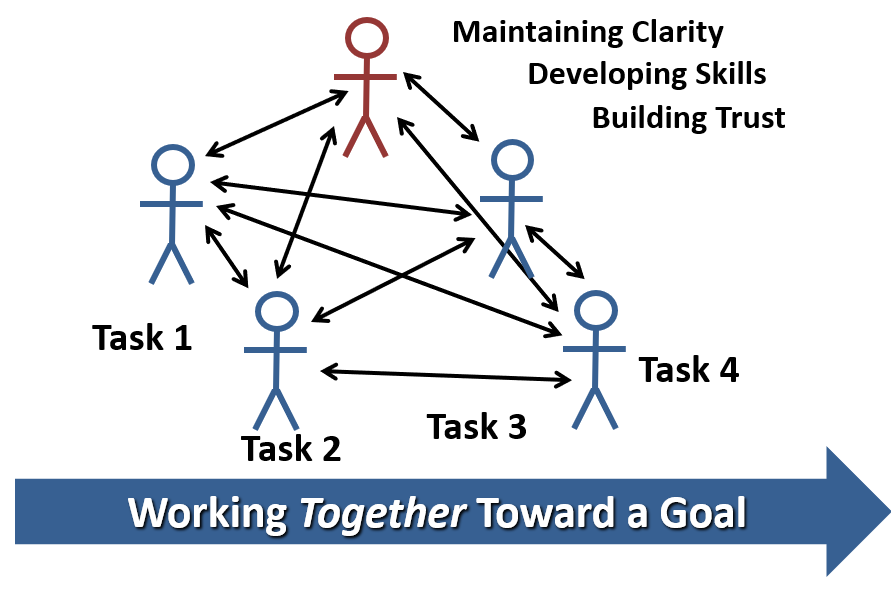

In this paradigm the emphasis is on teamwork rather than “do your job.”

“Teamwork” is interesting. People tell me they want “teamwork” within their organizations as though teamwork is a tangible thing. It isn’t. Teamwork is an emergent property of specific habitual patterns of interaction between people. When those interconnections are strong, there is teamwork. When those interconnections are weak, then people tend to retreat into their own individual silos.

The supervisor’s role in this model is much less directive. Their objectives are around maintaining clarity so that the entire team is aware of how they are doing vs. their objective; to work to build trust with and between the members of the team; and work to grow people’s skills, both technical and social.

The objective is centered around strengthening the team.

What kind of things do I observe when this model prevails?

Relationships are Social

This doesn’t mean that everyone is friends or socializes outside of work (though that can happen). It doesn’t even mean they all like each other. Rather, there is a bond of trust and respect between the members of the team. This isn’t just about the interactions between individuals and the supervisor, but interactions between everyone.

Sidebar: It your organization refers to employees in terms such as “team member” but still engages in traditional transactional relations focused on compliance and control, the values in your language do not reflect the values people actually experience, and you are only fooling yourself.

Motivation is Considered to be Intrinsic

Human motivation is probably the thing we have learned the most about since the 1940s. There is a robust body of research that suggests that transactional, extrinsic, motivators alone actually reduce teamwork, reduce the level of commitment, and impede creative problem solving because they introduce a fear of loss into the transaction. Organizations that have strong teamwork also understand this.

They work hard to build a workplace that creates a sense of autonomy, competence, and most critically, relatedness – the sense of satisfaction from relationships and being a part of something bigger than ones’ self.

And crucially, these organizations tend to consider all employees, regardless of level, to be vested members of a single entity rather than transactional employees. Note that I say “employees” here but I am not implying any particular legal relationship. I have seen phenomenal teamwork and intrinsic motivation within groups of independent contractors, or hybrid groups with both independent contractors and formal employees. I have even seen it with team members who were technically employees of a temp agency.

This feeling of being vested in the teamwork and the outcome arises from the relations between the team members, not any particular legal structure.

Assumption: Good Teamwork Produces Better Results

In the strongest teamwork cultures, the lowest level of accountability for results is the team. Admittedly this is exceptional, but it demonstrates a basic underlying assumption: The way to get the best performance is to focus on strengthening teamwork rather than reacting directly to things that disrupt production.

Now… reality is more subtle than this, of course. But that really means that the leadership, especially the first line leadership, must be steeped a mindset of learning and growth rather than one of simply gaining compliance.

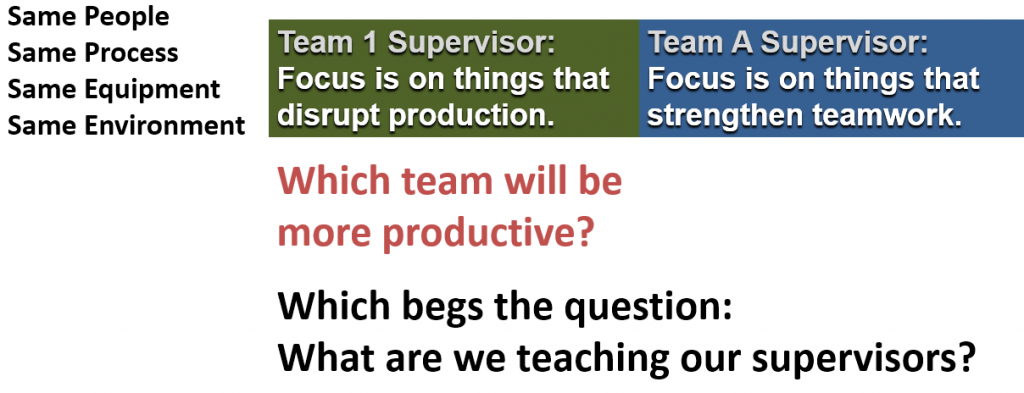

A Thought Experiment – Which Team Do You Want?

Consider this hypothetical. We have two groups that are identical.

- The same people.

- The same process.

- The same equipment.

- The same environment.

The supervisor for Team 1 has a focus on things that disrupt production.

The supervisor for Team A has a focus on things that strengthen teamwork.

Which of those teams will be more productive? Team 1? or Team A?

I asked this question to an audience of about 60 people (as I gave this talk) at the 2023 TWI Summit. Nobody raised their hands for Team 1. About two thirds raised their hands for Team A. Strong teamwork produces better results.

Getting the Facts: What Does TWI Job Relations Actually Say?

Which brings us back to our original question: How do we define “good” in “Good Relations?”

The 1944 Job Relations trainer’s manual is silent on any direct definition of “Good Relations.” Therefore we have to look at what the material defines as the objective of the supervisor.

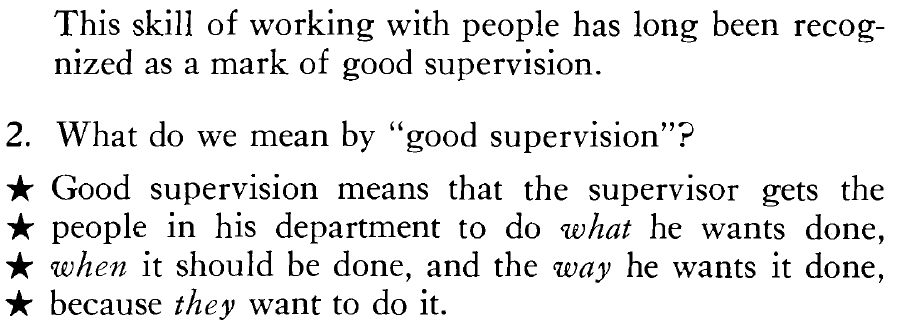

In the introductory material on day one, we see this definition of “Good Supervision” at the bottom of Page 18 in the 1944 Job Relations manual:

Good supervision means that the supervisor gets the

people in his department to do what he wants done,

when it should be done, and the way he wants it done,

because they want to do it.

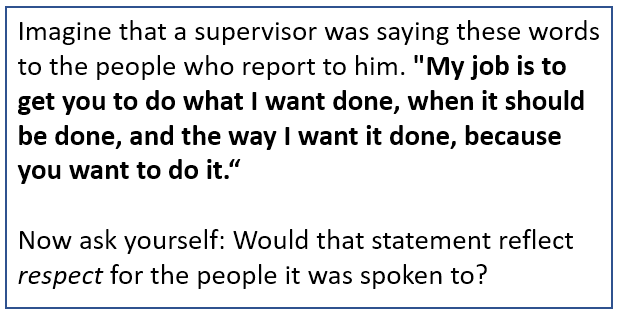

Are you comfortable with this definition of “good supervision?”

All I can do here is relate my own reaction. Yours may be different. But to me, this is the very definition of compliance. Most updates to the material change the pronouns from “he” to something more inclusive, but the rest of the words remain, and are often quoted outside of the actual class.

Is this the objective? Is this the relationship we want our supervisors to have with their people? Only you know what your objective is.

Here is a little test you can do. Take this definition of “good supervision” and frame it in the first person. Imagine that a supervisor was saying these words to the people who report to him. “My job is to get you to do what I want done, when it should be done, and the way I want it done, because you want to do it.”

Now ask yourself: Would that statement reflect respect for the people it was spoken to? Would it fly when spoken to members, especially the youngest members, of a 21st century workforce? Does that statement meet the objective of good relations between a supervisor and his direct reports?

If teaching your supervisors how to constructively gain compliance from their people is your goal, you can stop reading. This post is not targeted at you.

But if you are after a different objective, then perhaps we should rethink the words we use when instructing. And, more importantly, we should rethink the words we teach others to use when teaching them to deliver this training material.

The Job Relations Model

If we were to hypothetically change the definition of “Good Supervision” to something a little more aligned with 21st Century values (or keep it if your values are aligned with it… why are you still reading this?) and look at the rest of the material, we see that we may have now created some discontinuities that need to be addressed.

The question remains: Does the model we use to teach these concepts support our objective?

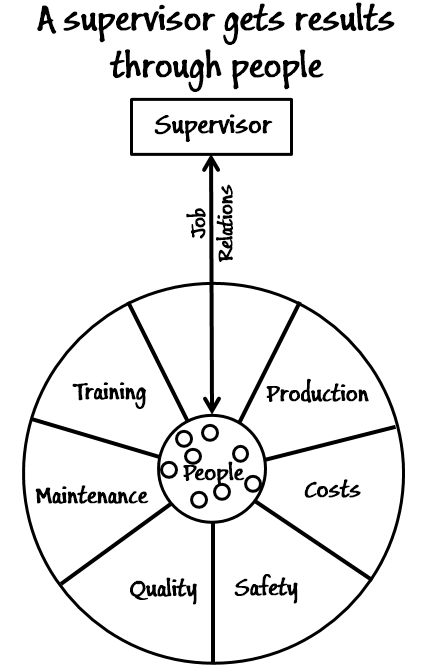

In the 1944 course, the instructor constructs this diagram step by step with the objective of emphasizing that success of supervisors depends on the “loyalty and cooperation” of the people working for them.

The first step of building the diagram is to emphasize that “A supervisor gets results through people.” by making the valid point that it is the people actually running the machines and assembling the product (or in more modern language, performing the value-adding operations) that actually get the results.

Did that supervisor himself make wire? No, he supervised a department in which many people worked together to turn out the wire.

Now this is really just a quibble on my part, but is there a better way to say that the supervisors’ job is to enable their people to get good results rather than “the supervisor gets results…” which, in my mind, lays claim to them?

I’m just throwing that out there, but overall, the tone seems to me to be more about authority than teamwork.

If I look holistically, I think the supervisor is more about enabling the team to get results by working on removing barriers to teamwork and getting the job done in the most effective and efficient way possible.

As the vertical two-ended arrow labeled “Job Relations” is drawn, the training script directs the instructor to say:

“Job Relations are the everyday relations between you [the supervisor] and the people you supervise.

The kind of relations you have affects the kind of results you get.

Relations with some are good, with others are poor, but there are always relationships.

Poor relationships cause poor results ; good relationships

cause good results.When a supervisor wants to meet any of these responsibilities effectively, he must have good relations with his people.

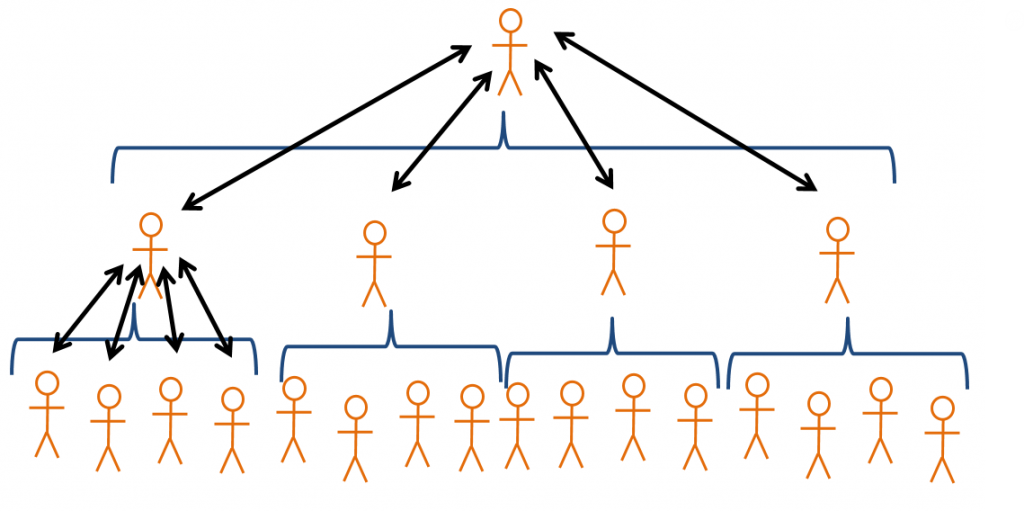

And all of this is totally true. What is not here is emphasis on the relations between the people. In fact, the word “trust” appears nowhere in the baseline material. “Teamwork” is mentioned only as “Lack of teamwork” in the list of possible problems a supervisor might encounter. It certainly isn’t a point of emphasis as a core objective.

So to someone who already has a mechanistic mindset, it is easy, in my mind, for that person to interpret this material as reinforcing a model where the supervisor uses his authority to oversee each member of the group individually with the overall objective of each one doing his job so that their piece of the process functions correctly.

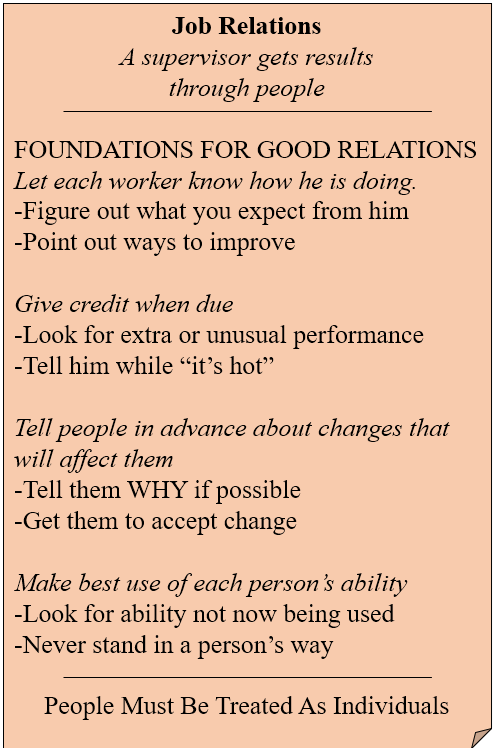

The Foundations for Good Relations

The 10 hour course spends 10 minutes going over the “Foundations for Good Relations.”

They are:

- Let each worker know how he is doing.

- Give credit where credit is due.

- Tell people in advance about changes that will affect them.

- Make the best use of each person’s ability.

and at the bottom of the pocket card: People must be treated as individuals.

What is really interesting to me here is that, according to the 1945 Training Within Industry Report that outlines the development of these courses, an earlier version of these foundations was (Bold emphasis added by me):

- Be sure that each person understands what his job is.

- Be sure each person understands the working conditions.

- Be sure each person understands what affects his earnings.

- Be sure that the people on the team work together.

So earlier, pilot, version of the material from early 1942 (at the latest) included an explicit reference to teamwork as a foundation for good relations, but this was changed by the time the final 1944 version was finalized. And it is the 1944 version that everyone who teaches TWI Job Relations bases their materials on.

Although the foundations are pretty solid, I personally find the phrasing a bit paternalistic – which, again, reflects the values of the times. Thus I think we should review the foundations and choose our words carefully when teaching these critical concepts.

The other question I have is this: Since these foundations are a critical underpinning for the entire program, why do we only spend 10 minutes telling them about the foundations? From TWI Job Instruction we know that “telling alone is not enough” for something that is critically important.

Again, according to the official history of the program, earlier pilot versions spent more time on the foundations, but that time was given up in order to spend more time on what is now the main emphasis of the course: “How to handle a problem.”

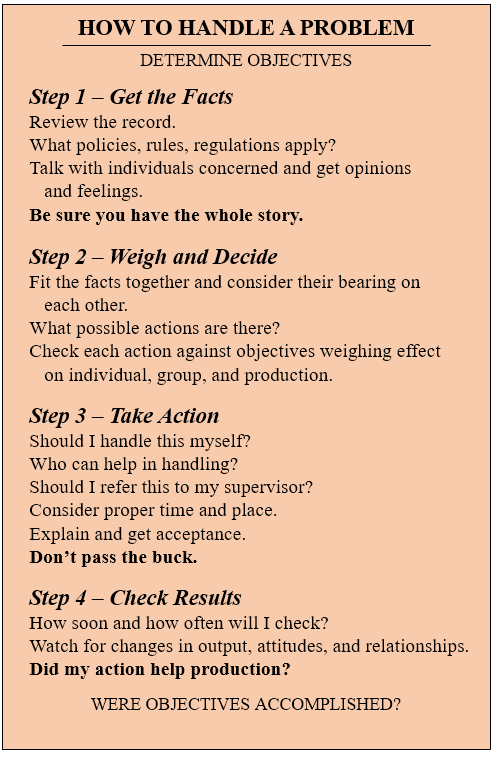

How to Handle a Problem

The course defines a problem as: “Anything the supervisor has to take action on.” and right away we set the tone for the remaining 8 hours and 55 minutes of the course – Problems.

What is awesome about TWI Job Relations is the Four Step Method for “handling problems.” What I wish were different is that it is framed to be about handling problems that cannot be ignored rather than a more general purpose process for developing people and teamwork. The process itself needs no changes. Only the title and context of teaching.

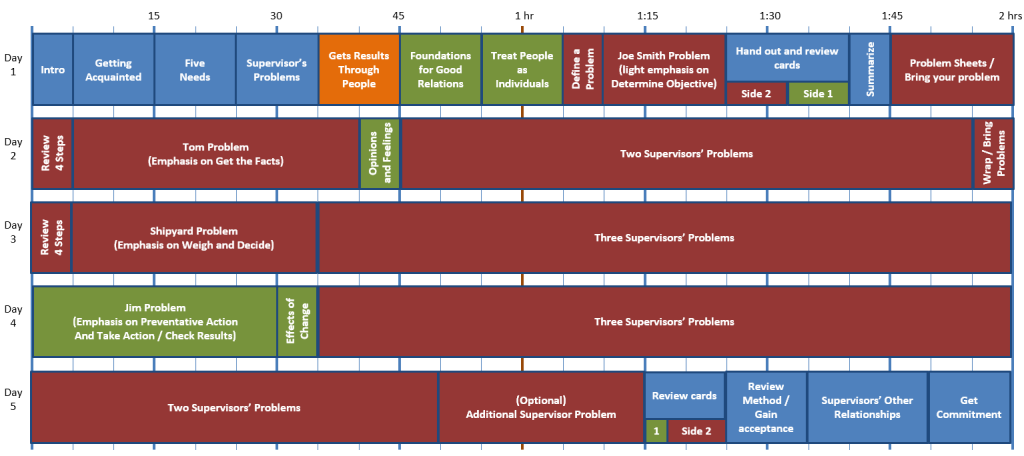

I think this point is driven home by the way the 10 hours course spends people’s time.

What Does TWI Job Relations Emphasize?

A simple look at the overall timeline of the course is telling. It spends slightly over 10% of the time talking about the foundations (in green above), the importance of good relations. And it spends just under 75% of the time practicing how to handle compliance issues (in red above). With the exception of “The Jim Problem” the case studies are around people having poor attitudes, not showing up for work, etc. And the case studies tend to set the tone for the “problems” that the participants bring to the class.

In the examples, the instructor emphasizes listening to people, though there isn’t any real practice around good listening skills. Again, earlier pilot versions of the course emphasized this more, but not the final version that everyone uses today.

OK, I could dig in more, but I’m not going to. Hopefully if you are considering using this material, you will read it for yourself, or listen to the words actually used, and ask yourself if these points of emphasis are what you want to teach your supervisors. Time for the next step.

Weigh and Decide

First, let me address some obvious (to me) potential objections to what I am saying so far. Then let’s look at alternatives, and finally, let’s ask which alternatives is most likely to meet our objective.

But Mark…Supervisors have to learn to deal with these real-world issues.

Yes they do. My questions are:

- Are the case studies reflective of issues that 21st century supervisors have to deal with?

- Are we giving our supervisors 21st century skills to deal with these their issues?

- Are we emphasizing teamwork or compliance?

I don’t disagree at all that our objective includes teaching supervisors how to effectively handle problems. I question whether the tone and phrasing we are using is the most effective way to do so.

But Mark… I (we) absolutely emphasize building good teams when teaching Job Relations.

If so, that is awesome. My questions are:

- Are you following the Job Relations course script, or are you deviating from the script to emphasize these things?

- Are you having to emphasize these things in follow-up after the formal class?

- If you are deviating from the script, then my message is not directed to you, BUT…

Do we teach new instructors to follow the script exactly?

If so, then my questions are:

- Do those newly certified Job Relations instructors already work in a place with a solid teamwork-based mindset (or a place striving toward one)?

- Do the words we teach them to say reinforce that teamwork mindset?

- What happens when the norms and customs of the organization are focused on compliance and production numbers only?

- Do those same words reinforce the mindset of compliance and production?

Are We Meeting Our Objective?

That depends very much on what your objective is.

If your objective is to prevent (or recover from) disruptions to production by teaching your supervisors to get people to do what he wants done, when it should be done, and the way he wants it done, because they want to do it, then everything is fine. The 1944 TWI Job Relations material is focused on this objective and does a great job.

If, on the other hand, the objective is to teach supervisors the skills they need to build a culture of teamwork, as well as to build a cadre of instructors who emphasize the things that contribute to that culture, then maybe, just maybe, we should take a look at the words we use.

And the words we teach others to use. And what we have them practice. And where they spend their time.

Job Relations is great. And when it is taught and coached through a lens of teamwork culture, it can have a profound positive impact on the organization.

But out of the box, I believe it is too deeply tied to the values and paradigms of its times.

I think we can do a better job preparing our supervisors for the next 80 years.

Conclusion

This is long enough, and I am not going to delve into any specific suggestions here. As I said at the beginning, this is public domain material, nobody owns it or manages the configuration. Anyone who wants to is able to take this as a baseline and update it to match your own values.

If you do, I would hope that you would consider re-contributing your updates to the public domain, so that our community can benefit as a whole.