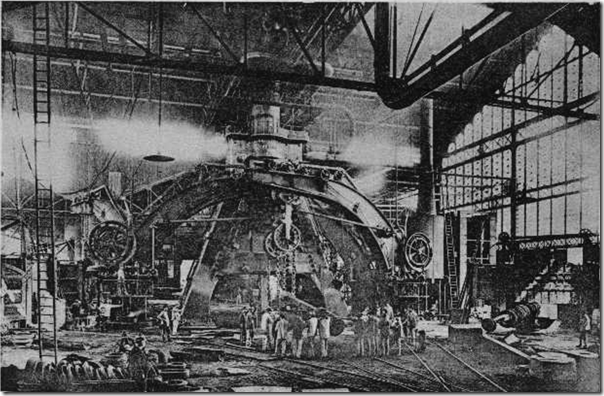

Imagine a factory with a large monument machine. It takes several days to set up. When it does run, it runs very fast, much faster than you can actually use its output. Therefore, you take the excess output and store it to use later. Actually, you don’t know how many items you need to make, so you make as many as you can while the machine is available to you.

Some of that excess output may prove to be less useful than you thought, but there is pressure to use it all anyway since it was so expensive to produce.

After a run making items for one process, you change it over to make items for a different process, and build up a queue of output there.

When all of the output is used, it all may or may not work the way you expected it to.

Most of us would see this as a classic case of “overproduction” – overwhelming the system with excess output that hasn’t been checked for quality, that isn’t needed right now, and might or might not be useful in the future. But it seemed like good efficiency to make it while we could.

Our lean thinking tells us we want to do a few things here. Ultimately, we want to work hard to break up the batches, and make the value flow more evenly to each of the customer processes, and ultimately to the end customers. The work we must do to keep things moving smoothly and evenly will pay off in both tangible and intangible ways.

One of the primary reasons we push hard for 1:1 flow in the lean world is to enable one-by-one confirmation.

We want to test each item of output to confirm that it actually performs as expected rather than making lots of them without knowing if they are any good.

How Do You Produce Improvements?

Now, imagine doing improvements this way. What would it look like?

A process would be scheduled to receive the rapid output of the Improvement Machine.

The Improvement Machine would be set up over a period of several days to produce improvements for the target process.

Once it was running, we would run the Improvement Machine very fast for a week or so. It would produce improvements faster than the target process can really absorb them.

At the end of the run, we might test the improvements as a batch. We might not test them at all, but rather report that they have been implemented with the assumption that they will work. We would also have excess improvements stored on a to-do list for future use.

Those excess improvements might, or might not, prove to be useful, but we would have huge pressure to implement them because they are on the list.

Once the machine was done producing improvements for one process, it would be set up to produce improvements the same way for another.

We would measure how many times we were able to run the improvement machine in a year, not so much the actual sustained impact we were making.

Improvements that were made without the machine might not be measured or credited at all. Or worse, these rogue improvements might actually be discouraged since they are made by people who aren’t certified to run the machine.

Now… substitute “kaizen event” for “improvement machine” and see if it makes any sense.

Why Are Big Batches Necessary?

The reason the Large Monument Machine has to cycle batches of output to different customers is because those customer processes don’t have the internal capability to do what it does. We need an outside resource to do it.

The countermeasure we strive to apply in these cases is to identify the capability that the customer process does need. We then work hard to develop it on a scale they can incorporate into their daily work. This is typically smaller, more specialized, and scoped to their needs.

My purpose here, though, is to apply a metaphor, not to discuss the economics of large capital equipment.

When we “batch improvements” it is often for the same reason: The area that is being improved can’t do it themselves, so we have to dedicate a scarce outside resource – an improvement expert – to lead them through it. Since that improvement leader can’t be there 100% of the time, he has to work as hard and fast as he can when he IS there.

Making Improvements vs. Teaching How to Make Improvements

The countermeasure in both scenarios is the same: Develop the capability within the process. In the case of making improvements, this means asking ourselves “Why can’t they do it?”

- Because they don’t know how? –> Something we need to teach.

- Because they don’t think it is important? –> Something we need to communicate, through a challenge.

- Because they “don’t have time?” –> Something we need to better understand and address.

All of these are harder than just doing it for them. But if we want improvement to flow, this is the work that must be done.

I like the comparison of Kaizen events to monuments. This can be very true, although there is a time and a place for them. My experience has been, though, that I’ve gotten better results and my customers have been more satisfied taking a workshop approach, with a few hours or a day as needed, breaking the improvement process up over several days, weeks, or even months, which gives the improvement process the necessary time intervals to perform needed PDSA. Leadership also has liked the way their resources aren’t consumed in large chunks of time.

Kaizen events fit nicely into consultants’ schedules, though, and make big money for consulting companies

😉

Mark –

Your last thought – that the week long event is built around travel schedules is likely right-on.

Looping back around to the top of your comment: “There is a time and a place for them.”

I agree, sort of. All of the evidence I have suggests that the origin of these events is training rather than the primary intent to make a lot of changes.

In fact, that is how I use those events today. Superficially the structure is similar. The difference is the intent. My goal is to kick-start a process of making, and discussing (using the Toyota Kata structure) a trial or improvement every day.

Those daily improvements or experiments are aligned on meeting a specific target condition which, in turn, is on the way to a longer-term organizational challenge.

At the end of the week, we don’t have a list of action items to complete. The “change” has been more to establish and practice a new daily routine. Thus, instead of those long to-do lists (excess WIP of ideas and improvements), we have “the next step” and each step taken identifies the next step to take. Now we are doing 1:1 flow of improvements with pull(!).

Your structure of breaking these things into smaller chunks is the same idea. Each chunk is tested and anchored (checked for quality, fitness-of-use, modified as necessary) before moving on to the next. Thus, you are moving toward one-by-one flow with smaller batches.

The whole point, I think, is that there is a limit to how quickly an organization, ANY organization, can absorb change. Exceed that limit, and it isn’t going to work. The capability to absorb change can, itself, be improved through practice.

Well said, Mark. Sounds like we’re essentially on the same sheet of music.