I am going to start off by acknowledging that my background with Six Sigma and its other x-Sigma flavors is mostly anecdotal. I have read the books, I have worked as a Quality Director in a company with a lot of Six Sigma background, and I have done a lot of continuous improvement work with people who had Six Sigma context. I understand most of the mechanics, but I have never personally used the pure DMAIC process to do a “project.”

With those caveats out of the way – I’ve been having some rich conversations about bringing the Toyota Kata framework into a Six Sigma culture without making Kata something foreign and alien.

I actually kind of addressed this back in 2014 with this post. But the recent discussions have had me think about it more, and it’s been 10+ years, so let’s go through it again.

And finally, before I get into the meat, PLEASE comment and discuss. I’m not putting this out there as fact, but more as a possible hypothesis. I am here to learn. If enough people show interest, we can even set up a Zoom call and dig in more if you want.

The Improvement Kata

This part will go into a lot more depth than I originally intended to, but I felt the need to establish some kind of fundamental baseline of the Improvement Kata for the Six Sigma audience that might have come here thorough a search engine. That being said, this is a brief overview of what the Improvement Kata is about, not a comprehensive reference.

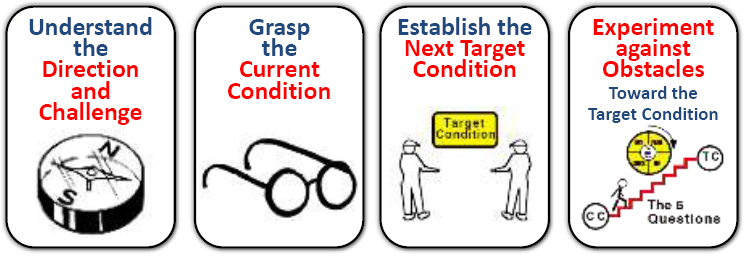

The Improvement Kata has four major steps. What follows is my interpretation which has been developed over the last 15 years of trying to apply them and teach others to do so.

These are steps that we coach the learner / improver through as they are trying to tackle a challenge.

Understand the Direction / Challenge

The key word here is understand. One way an organization with a strong culture of developing people does so is by challenging them to take on something that is going to stretch their capability. This is different from a traditional “stretch goal” that might have some kind of bonus attached to it, because this challenge comes from a leader / coach who is taking on the responsibility of making sure the improver succeeds. I think the best story of how this really works is in The Toyota Way of Lean Leadership by Jeff Liker and Gary Convis. (The book links in this post all take you to the Amazon listing. If you click through and buy something I get a small kickback at no cost to you that helps me run this site.)

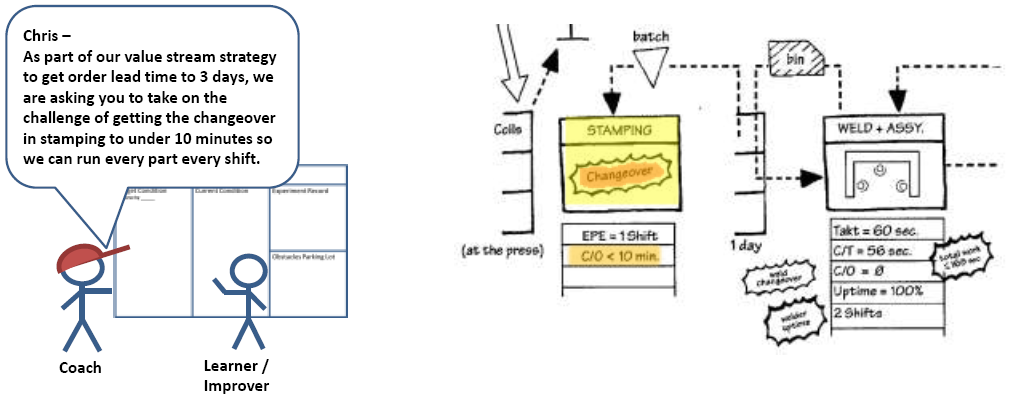

Mike Rother’s first book, Learning to See describes the process of mapping a “value stream.” An outcome of that process is understanding the things that must change or improve for the Future State to work the way we have designed it (the “kaizen bursts”).

The value stream map clip on the right side of this picture is taken from the book. On the left is the conversation a manager / coach might have with the supervisor of the stamping area.

Toyota Kata Culture by Gerd Aulinger and Mike Rother offers a good example of this. This is a video of Gerd’s presentation to Kata School Cascadia on the process of developing problem-solving capacity and cascading goals.

There is an alternate form of this step, where it is up to the learner to determine their challenge. In a corporate world that is much less than ideal. It is appropriate, though, for people working with a coach to practice the Improvement Kata on a personal goal of some kind.

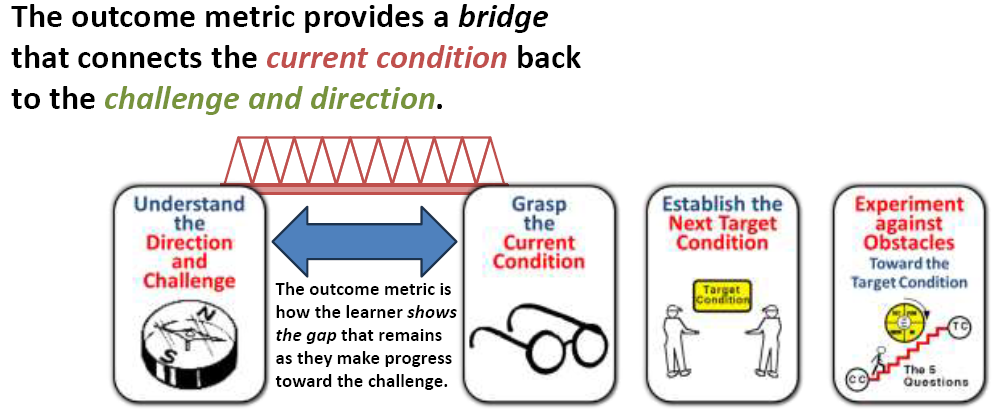

In either case, we want to end up with a way to know when we have met the challenge. We usually call this the outcome metric. I like to say that the outcome metric is what bridges between the Challenge and the Current Condition.

Once the outcome metric is understood, we should immediately start charting it. This is the first step of Grasp the Current Condition.

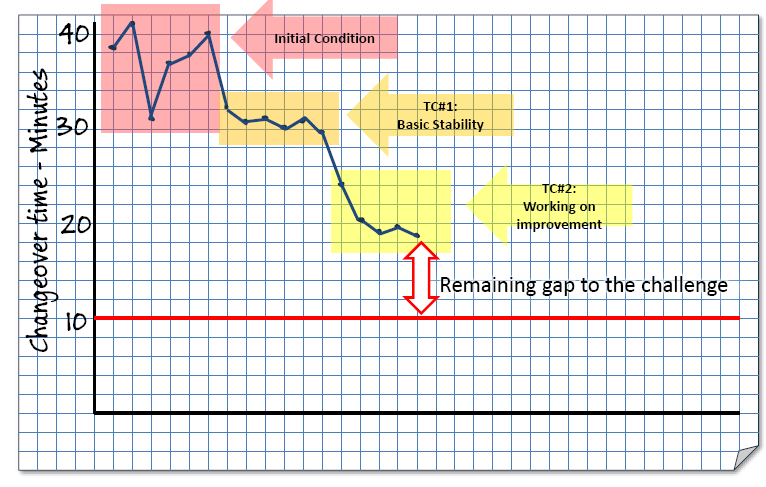

This example shows a hypothetical changeover time as the learner progresses through a few Target Conditions on their way to the ultimate 10 minute challenge.

Grasp the Current Condition

In this step we (the coach) guide the learner through a series of steps designed to help them gain understanding of what is actually happening in the process. We want to go beyond outcomes and results, and understand the dynamics of the system. Ultimately we want to develop a cause-and-effect understanding between the process itself and the results that we want to improve.

The starting point is to understand how we are going against the challenge, and then to understand what the customer needs and when they need it. Then we dig into understanding the “normal operating patterns” within the process itself.

It is really important here to exercise some discipline and resist the urge to start brainstorming ideas of things we can change. This can be challenging in an organization with an “action now” bias, and it is up to the coach to keep a gentle but firm foot on the brake pedal to keep things from careening down the mountain.

The goal of this step is to get enough information to make an informed choice about what we want to work on next. This is not necessarily exhaustive information about everything. One advantage of this approach is that by progressively narrowing the focus, we can keep the details relevant to the problem we are trying to solve right now.

Establish the Next Target Condition

This is a point of decision: What are we going to strive for next? Often the challenge is daunting. A Target Condition narrows the scope, and brings the timeline down to (usually) a couple of weeks. In the example run chart above, the Learner likely saw that the current changeovers were wildly inconsistent, and made a decision to go for stability first. That is usually a good place to begin. Until there is some stability it is hard to see the effect of future improvements.

Process Metrics

A key component (maybe THE key component) of a Target Condition is what we call a process metric. That is the thing we are actually working to change.

Often (almost always) the Challenge (which we are measuring through the Outcome Metric) is a dependent variable – something we cannot directly impact. For those of you who have not tired of sports analogies, this is the score of the game. In the words of a local celebrity sports commentator from the late 90s here in Seattle, “All you have to do to win every baseball game is score more runs than the other team.” True, but not actionable.

The process metric is usually an independent variable – something that is driving the outcome. In other words, something about the way the game is played. These are things we can affect.

I can’t just say “we are just going to make more units per shift” but I can work on improvements that impact the cycle time. I can’t just say “we are going to make the changeover 10 minutes,” but I can work on reducing the tasks that must be done while the machine is stopped.

Obstacles

Part of establishing a Target Condition is to ask some form of, “Why can’t we just do this now?” What we are looking for is Obstacles – the characteristics of the current process or environment that make it hard to change the process metric. In the language of TPS, those are problems. Another company I work with chooses to call them “issues.” The words matter a lot less than the understanding – these are the things we need to work on.

It is also common (normal?) for the initial obstacles to be more about things we need to understand better before proceeding. Our focus is narrowed now, and we may have to go back into Current Condition mode, just with finer granularity. “Where does the time actually go?”

Experiment Against Obstacles

Mike Rother’s book The Toyota Kata Practice Guide describes everything up to this point as the “Planning Phase,” and the actual process of experimenting (really LEARNING) as the “Execution Phase.” My awesome friend and amazing Kata Girl Geek, Gemma Jones, has started calling this the “Striving Phase” and I think that describes what we are doing much better.

(My original review of the Practice Guide from when it was first published is at this link. )

The simple fact is that we don’t know the answers or solutions that are going to get us there. They need to be discovered, to be learned. We learn by running experiments to test ideas, to get more information.

One key thing that distinguishes Toyota Kata from other similar descriptions of PDCA is that Toyota Kata makes the iteration explicit. This isn’t a one-and-done process.

An experiment is an action step the learner plans to take AND a prediction of what will be learned, or what impact that step will have on the process (metric).

Each experiment is followed by reflecting on what actually happened vs what was predicted and what was learned. That learning, in turn, informs the next step.

Iterate

The Improvement Kata is a process of nested iteration. We are iterating experiments against obstacles on the way to a Target Condition. Once a Target Condition is achieved (or the achieve by date reached without achieving the TC), first pause and reflect on what we have learned, then we iterate back through confirming our understanding of the challenge, grasping the current condition, and establishing the next target condition.

It is important to do this because we have been narrowly focused, and it is likely that the changes we have been making have had an effect on parts of the process we have not been explicitly working on. No matter what, the Current Condition has changed, so it is important to use up-to-date information to establish the next Target Condition.

Coaching

The whole point of this process is to solve the problem in a way that improves peoples’ problem solving skills. This is where the coach comes in.

Where the learner is working on the focus process of the challenge, the coach is working to improve the process of how the learner thinks. That is why we often give the challenge to someone who needs to grow into handling it.

The coach’s main job is to keep the learner between the guard rails of good scientific thinking. The structure of the “5 Questions” Coaching Kata is a starting place for the coach to develop the skills required to help others think more clearly.

Mapping to DMAIC

Another term we use in Toyota Kata world is “threshold of knowledge.” This is the boundary between, “things I actually know” and “things I might be speculating about.” That boundary notoriously easy to cross without knowing it. It is easy to start treating our assumptions as known facts.

I said all of that because I am talking about DMAIC, and I am way beyond my threshold of knowledge about the nuts and bolts. Feel free to correct and enlighten me where I have gotten something fundamentally wrong. However I am trying to keep this at the level of the principles, so I’m not going to go into the gritty details of statistical tools at all.

Define

As I understand it, the main goal of the Define step is to be clear about the problem we are actually trying to solve. I do not see a fundamental difference between this step and the “Understand the Direction / Challenge” step of the Improvement Kata. I believe both should give us a clear outcome gap we are trying to close.

Measure

Right away the word “measure” can impose a limit on thinking. I believe there is a lot more involved than just numbers. Though the tools may be different, Measure maps pretty will in intent to the Improvement Kata step of Grasp the Current Condition.

The Voice of the Customer step examines the same things – what does the customer need, and when do they need it. Since Six Sigma has roots in the Quality Movement, there may be more depth here, which is awesome. The Improvement Kata is a starting point, and is not prescriptive (or proscriptive) of any tool or technique that helps us gain better understanding. The goal is the same.

We are still mapping the process, and working hard to gain understanding of where problems occur (for example).

Statistical tools can (sometimes) help gain more understanding. For example, the classic SPC chart can give us insight into whether a particular part of the process is operating the way we should expect it to (“common cause variation”) or if it is being continuously disrupted by outside forces and true anomalies (“special cause variation”).

That being said, MY caution here is that statistical tools can often become a “wrench in search of a screw to pound” – knowing them is not equivalent to needing them for any particular problem.

Analyze

Now we are looking at what we have learned and making decisions about where to go first (or next). DMAIC is not explicitly iterative, put in practice I think it is.

The outcome of my analysis is analogous to a Target Condition. Instead of obstacles, we have things like sources of variation, but those are still the problems we need to better understand and solve.

Improve

If I am doing this well, then I am running experiments. I have ideas, but I have to test them to see if they are worth pursuing, and then if they actually have the impact on the process that I expect them to.

So this isn’t just brainstorm a list of action items and implement them.

If I were coaching a Six Sigma minded person, instead of asking about “obstacles” I might ask, “What sources of variation are keeping you from reaching your Target Condition, and which one are you addressing now?”

Improve maps very well to the “Experiment Against Obstacles” step of the Improvement Kata.

Control

It is interesting (to me) that this is listed as a separate, discrete step. But “standardize” as a separate step is pretty common in a lot of “lean” circles. I doesn’t work that way.

The complaint I often hear from change agents is that “management” (or “they”) “are not supporting the changes.” What exactly does that mean? What, exactly, do you expect to be different? In other words, what changes have you made to the daily management system itself?

Let’s look at the goal of that statistical control chart. Yes, it is telling us if the process is “in control” or “not in control.” But what happens if it isn’t? A data point goes outside the control limits; or the mean actual mean has shifted to a point above the historic mean. What do you expect to happen now?

All the chart does is give us information, it doesn’t actually “control” anything. It tells us when intervention is appropriate.

All of the so-called lean tools do this. They are instruments that tell you if your process is operating as it should, or if something else is happening.

But unless that information triggers immediate intervention to learn more, correct back to the standard condition, and start to understand what we need to do to prevent that problem from recurring, then the process will inevitably erode. “You can’t just decide the freezer is cold enough and then unplug it.” You have to keep putting some amount of energy into the system just to maintain it.

Control, then, is a process, just like any other. This is the heart of your shop floor daily management system. If done well, then every day things run a little smoother. If not, well, they don’t.

So “control” is really part of “improve.” If they aren’t done in rapid iteration then you are unlikely to hold any gains.

A saying from one of my ex-Toyota coworkers was “No problem is a BIG problem.” If things are running smoothly it doesn’t mean there are no problems. It means your system is blind to them. Time to investigate further.

Conclusion

OK, I’m going to resist the temptation to go off on deep dive tangents and stop here. This is already too long.

Hopefully this creates some discussion. I’d love to hear from you.

A few points from someone with over 20+ years of experience using both Lean and Six Sigma:

1. I think the methodology of Six Sigma (DMAIC) is more explicit in what you have to when solving problems vs Lean (PDCA). I would argue that Define, Measure, and Analyze (and possibly part of Improve) are all within Planning. This is helpful for new learners and emphasizes the amount of work required BEFORE you get to discussing solutions!

2. Measuring is about collecting data – something not intuitive or initially obvious in Lean. So WHAT are you going to measure? Does that metric provide the best way to view your improvement in the short piloted solutions/experiments you will run later? HOW are you going to measure it?

3. Is your measurement system accurate enough to describe the current state? What bias might be in the data? Is the sample appropriate to understand the current state? This is called Measurement System Analysis. It might be the MOST important part of the Measure phase. My experience is that many Lean practitioners don’t have a good grasp of how to do this.

4. The Control Plan in the Control phase should explicitly document WHO is going to measure the process going forward, HOW often, and WHAT they are going to measure. It also identifies the ‘specification’ they are comparing the measurement to. If it’s out-of-spec, then the response is clearly stated about WHO is going to do WHAT WHEN. Lean might do this, but I’ve not seen it in a formal way. In organizations like Toyota, this is imbedded into their system – but what about the other 99% of organizations where this isn’t? The trap is most organizations NEVER revisit their Control Plans to see if they are still valid or if changes are necessary to continue sustaining the improvement.

The complaint about management not ‘supporting’ them is VERY common – usually in organizations where leadership doesn’t practice continuous improvement and the Quality group is responsible for improvement instead of leadership (and most specifically the ‘Operations/Production’ group). Clearly identifying a Process Owner and Project Champion can help with this, but doesn’t guarantee success. Leadership is usually happy with an ‘ozempic’ solution where they don’t have to modify/change their behavior – which could be an entire post itself!

Pete – thank you for your comment.

I wasn’t trying to compare DMAIC to anything “lean” but rather to the steps of Mike Rother’s Improvement Kata which is more about coaching and thinking the thinking patterns behind improvement in general than any specific branded approach.

I agree that Define, Measure, and Analyze, and likely early steps in Improve are all part of planning. The Improvement Kata steps map pretty much the same way as early experiments are often getting more information.

I agree that measuring is about collecting data, but I also think it requires understanding customer requirements (as a minimum what constitutes “defect free” and “on time”), understanding the process itself. I believe DMAIC calls out mapping the process, for example, as part of gaining basic understanding.

How are you going to measure it? Yup. In the Improvement Kata we identify our Outcome Metric as part of Understand the Direction / Challenge; and identify Process Metric(s) as part of Establish the Next Target Condition.

I think a “control plan” needs to go WAY beyond measurement. It has to include the process for response, restoring the standard, re-stabilizing the process.

Some of the differences here are differences between TPS as actually practiced at benchmark companies and so-called “lean” which is OFTEN depicted in a watered down, less rigorous process than what you find in pure TPS.