In past posts, I have referred to an organization that implemented a “morning market” as a way to manage their problem solving efforts.

Synchronicity being what it is:

Barb, the driving force in the organization in my original story, wrote to tell me that their morning market is going strong – and remains the centerpiece of their problem solving culture. In 2008, she reports, their morning market drove close to 2000 non-trivial problems to ground. That is about 10/day. How well do you do?

Edited to add in March 2015: I heard from Barb again. It is still a core part of the organization’s culture.

So – to organizations trying to implement “a problem solving culture” and anyone else who is interested, I am going to get into some of the nuts and bolts of what we did there way back in 2003. (I am telling you when so that it sinks in that this is a change that has lasted and fundamentally altered the culture there.)

What is “A Morning Market?”

The term comes from Masaaki Imai’s book Gemba Kaizen pages 114 – 118. It is a short section, and does not give a lot of detail. The idea is to review defects “first thing in the morning when they are fresh” – thus the analogy to the early morning fish and produce markets. (For those who like Japanese jargon, the term is asaichi, but in general, with an English speaking audience, I prefer to use English terms.)

The concept is to display the actual defects, classified by what is known about them.

- ‘A’ problems: The cause is known. Countermeasures can be implemented immediately.

- ‘B’ problems: The cause is known, countermeasures are not known.

- ‘C’ problems: Cause is unknown.

Each morning the new defects are touched, felt, understood. (The actual objects). Then the team organizes to solve the problem. The plant manager should visit all of the morning markets so he can keep tabs on the kinds of problems they are seeing.

Simple, eh?

Putting It Into Practice

Fortunately we were not the pioneers within the company. That honor goes to another part of the company who was more than willing to share what they had learned, but their key lesson was “put two pieces of tape on a table, divide it into thirds, label them A, B and C and just try it.”

They were right – as always, it is impossible to design a perfect process, but it is possible to discover one. Some key points:

- There is a meeting, and it is called “the morning market” but the meeting does not get the problems solved. The difference between the organizations that made this work and the ones that didn’t was clear: To make it work it is vital to carve out dedicated time for the problem solvers to work on solving problems. It can’t be a “when you get around to it” thing, it must be purposeful, organized work.

- The meeting is not a place to work on solving problems. There is a huge temptation to discuss details, ask questions, try to describe problems, make and take suggestions about what it might be, or what might be tried. It took draconian facilitation to keep this from happening.

- The purpose of the meeting is to quickly review the status of what is being worked on, quickly review new problems that have come up, and quickly manage who is working on what for the next 24 hours. That’s it.

- The morning market must be an integral part of an escalation process. The purpose is to work on real problems that have actually happened. Work on them as they come up.

Just Getting Started

This was all done in the background of trying to implement a moving assembly line. There is a long back story there, but suffice it to say that the idea of a “line stop” was just coming into play. Everyone knew the principle of stopping the line for problems, but there was no real experience with it. As the line was being developed, there were lots of stops just to determine the work sequence and timing. But now it was in production.

The first point of confusion was the duration of a line stop. Some were under the impression that the line would remain stopped until the root cause of the problem was understood. “No, the line remains stopped until the problem can be contained,” meaning that safe operations that assure quality are in place.

The escalation process evolved, and for the first time in a long time, manufacturing engineers started getting involved in manufacturing.

The actual morning market meeting revolved around a whiteboard. At least at first. When they started, they filled the board with problems in a day or two. They called and said they wanted to start a computer database to track the problems. I told them “get another board.” In a few days that board, too, filled up. It really made sense now to start a computer database. Nope. “Get another board.” That board started to fill.

Then something interesting happened. They started clearing problems.

PDCA – Refining The Process

The tracking board evolved a little bit over time.

The first change was to add a discrete column that called out what immediate measures had been taken to contain the problem and allow safe, quality production to resume. This was important for two reasons.

First, it forced the team to distinguish between the temporary stop-gap measure that was put in immediately and the true root-cause / countermeasure that could, and would, come later. Previously the culture had been that once this initial action were taken, things were good. We deliberately called these “containments” and reserved the word “countermeasure” for the thing that actually addressed root cause. This was just to avoid confusion, there is no dogma about it.

Second, it reminded the team of what (probably wasteful) activity they should be able to remove from the process when / if the countermeasure actually works. This helped keep these temporary fixes from growing roots.

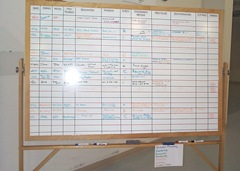

You can get an idea of what a typical problem board looked like here:

The columns were:

- Date (initial date the problem was encountered)

- Owner

- Model (the product)

- Part Number (what part was involved)

- Description (of the part)

- Problem (description of the problem)

- A/B/C (which of the above categories the problem was now. Note that it can change as more is learned.

- Containment Method

- Root Cause (filled in when learned)

- Countermeasure (best known being tried right now)

- Due Date (when next action is due / reported)

- Verified (how was the countermeasure verified as effective?)

A key point is that last column: Verified. The problem stays on the board until there is a verified countermeasure in place. That means they actually tested the countermeasure to make sure it worked. This is, for a lot of organizations, a big, big change. All too many take some action and “call it good.” Fire and forget. This little thing started shifting the culture of the organization toward checking things to make sure they did what they were thought to do.

Refining The Meeting

While this particular shop floor was not excessively loud, it was too loud for an effective meeting of more than 3-4 people. Rather than moving the meeting to a conference room, the team spent $50 at Wally World and bought a karaoke machine. This provided a nice, inexpensive P.A. system. It added the benefit that the microphone became a “talking stick” – it forced people to pay attention to one person at a time.

Developing Capability

The other gap in the process that emerged pretty quickly was the capability of the organization to solve problems. While there had been a Six Sigma program in place for quite a while, most of skill revolved around the kinds of problems that would classify as “black belt projects.” The basic troubleshooting and physical investigation skills were lacking.

After exploring a lot of options, the organization’s countermeasure was to adopt a standard packaged training program, give it to the people involved in working the problems, then expecting that they immediately start using the method. This, again, was a big change over most organization’s approach to training as “interesting.” In this case, the method was not only taught, it was adopted as a standard. That was a big help. A key lesson learned was that, rather than debate which “method” was better, just pick one and go. In the end, they are all pretty much the same, only the vocabulary is different.

Spreading The Concept

In this organization, the two biggest “hitters” every day were supplier part quality and supplier part shortages. This was pretty much a final-assembly and test only operation, so they were pretty vulnerable to supplier issues. This process drove a systematic approach to understand why the received part was defective vs. just replacing it. Eventually they started taking some of their quality assurance tools upstream and teaching them to key suppliers. Questions were asked such as “How can we verify this is a good part before the supplier ships it?” They also started acknowledging design and supplier capability (vs. just price and capacity) issues.

On the materials side, the supply chain people started their own morning market to work on the causes of shortages. I have covered their story here.

As they implemented their kanban system, morning markets sprang up in the warehouse to address their process breakdowns. Another one addressed the pick-and-delivery process that got kits to the line. Lost cards were addressed. Rather than just update a pick cart, there was interest in why they got it wrong in the first place, which ended up addressing bill-of-material issues, which, in turn, made the record more robust.

Managing The Priorities

Of course, at some point, the number of problems encountered can overwhelm the problem solvers. The next evolution replaced the white board with “problem solving strips.” These were strips of paper, a few inches high, the width of the white board, with the same columns on them (plus a little additional administrative information). This format let the team move problems around on the wall, group them, categorize them, and manage them better. Related issues could be grouped together and worked together. Supplier and internal workmanship issues could be grouped on the wall, making a good visual indication of where the issues were.

But those were all side effects. The key was managing the workload.

Any organization has a limited capacity to work on stuff. The previous method of assignment had been that every problem was assigned to someone on the first day it was reviewed. It became clear pretty quickly that the half a dozen people actually doing the work were getting a little sick of being chided for not making any progress on problems 3, 4 and 5 because they were working on 1 and 2. In effect, the organization was leaving the prioritization to the problem solvers, and then second guessing their choices. This is not respectful of people.

The countermeasure – developed by the shop floor production manager, was to put the problems on the strips discussed above. The reason she did it was to be able to maintain an “unassigned” queue.

Any problem which was not being worked on was in the unassigned queue on the wall. All of the problems were captured, all were visible to everyone, but they recognized they couldn’t work on everything at once. As a technical person became available, he would pull the next problem from the queue.

There were two great things about this. First, the production manager could reshuffle the queue anytime she wanted. Thus the next one in line was always the one that she felt was the most important. This could be discussed, but ultimately it was her decision. Second is that the queue became a visual indicator that compared the rate of discovering problems (into the queue) with the rate of solving problems (out of the queue). This was a great “Check” on the capacity and capability of the organization vs. what they needed to do.

There were two, and only two, valid reasons for a problem to bypass this process.

- There was a safety issue.

- A defect had escaped the factory and resulted in a customer complaint.

In these cases, someone would be assigned to work on it right away. The problem that had been “theirs” was “parked.” This acknowledged the priority, rather than just giving him something else to do and expecting everything else to get done too. (This is respect for people.)

Incorporation of Other Tools

Later on, a quality inspection standard was adopted. Rather than making this something new, it was incorporated into the problem solving process itself. When a defect was found, the first step was to assess the process against the standard for the robustness of countermeasures. Not surprisingly, there was always a pretty significant gap between the level of countermeasures mandated by the standard and what was actually in place. The countermeasure was to bring the process up to the standard.

The standard itself classified a potential defect based on its possible consequences. For each of four levels, it specified how robust countermeasures should be for preventing error, detecting defects, checking the process, secondary checks and overall process review. Because it called out, not only technical countermeasures, but leadership standard work, this process began driving other thinking into the organization.

Effect On Designs

As you might imagine, there were a fair number of issues that traced back to the design itself. While it may have been necessary to live with some of these, there was an active product development cycle ongoing for new models. Some of the design issues managed to get addressed in subsequent designs, making them easier to “get right” in manufacturing.

What Was Left Out

The things that got onto the board generally required a technical professional to work them. These were not trivial problems. In fact, at first, they didn’t even bother with anything that stopped the line for less than 10 minutes (meaning they could rework / repair the problem and ship a good unit). But even though they turned this threshold down over time, there were hundreds of little things that didn’t get on the radar. And they shouldn’t… at least not onto this radar.

The morning market should address the things that are outside the scope of the shop floor work teams to address.

Another organization I know addressed these small problems really well with their organized and directed daily kaizen activity. Every day they captured everything that delayed the work. Five second stoppages were getting on to their radar. Time was dedicated every day at the end of the shift for the Team Members to work on the little things that tripped them up. They had support and resources – leadership that helped them, a work area to try out ideas, tools and materials to make all of the little gadgets that helped them make things better. They didn’t waste their time painting the floor, making things pretty, etc. unless that had been a source of confusion or other cause of delay. Although the engineers did work on problems as well, they did not have the work structure described above.

I would love to see the effect in an organization that does all of this at once.

No A3’s?

With the “A3” as all the rage today, I am sure someone is asking this question while reading this. No. We knew about A3’s, but the “problem solving strips” served about 75% of the purpose. Not everything, but they worked. Would a more formal A3 documentation have worked better? Not sure. This isn’t dogma. It is about applying sound, well thought out methodology, then checking to see if it is working as expected.

Summary

Is all of this stuff in place today? Honestly? I don’t know. [Update: As of the end of 2011, this process is still going strong and is strongly embedded as “the way we do things” in their culture.] And it was far from as perfect as I have described it. BUT organized problem solving made a huge difference in their performance, both tangible and intangible. In spite of huge pressure to source to low-labor areas, they are still in business. When I read “Chasing The Rabbit” I have to say that, in this case, they were almost there.

And finally, an epilogue:

This organization had a sister organization just across an alley – literally a 3 minute walk away. The sister organization was a poster-child for a “management by measurement” culture. The leader manager person in charge sincerely believed that, if only he could incorporate the right measurements into his manager’s performance reviews, they would work together and do the right things. You can guess the result, but might not guess that this management team described themselves as “dysfunctional.” They tried to put in a “morning market” (as it was actually mandated to have one – something else that doesn’t work, by the way). There were some differences.

In the one that worked, top leaders showed up. They expected functional leaders to show up. The people solving the problems showed up. The meeting was facilitated by the assembly manager or the operations manager. After the meeting people stayed on the shop floor and worked on problems. Calendars were blocked out (which worked because this was a calendar driven culture) for shop floor problem solving. Over time the manufacturing engineers got to know the assemblers pretty well.

In the one that didn’t work, the meeting was facilitated conducted by a quality department staffer. The manufacturing engineers had other priorities because “they weren’t being measured on solving problems.” After the meeting, everyone went back to their desks and resumed what they had been doing.

There were a lot of other issues as well, but the bottom line is that “problem solving” took hold as “the way we do things” in one organization, and was regarded as yet another task in the other.

About 8 months into this, as they were trying, yet again, to get a kanban going, a group of supervisors came across the alley to see what their neighbors were doing. What they saw was not only the mechanics of moving cards and parts, but the process of managing problems. And the result of managing problems was that they saw problems as pointing them to where they needed to gain more understanding rather than problems as excuses. One of the supervisors later came to me, visibly shaken, with the quote “I now realize that these people work together in a fundamentally different way.” And that, in the end, was the result.

In the end? The organization in this story is still in business, still manufacturing things in a “high cost labor” market. The other one was closed down and outsourced in 2005.