Once again I am going through old files. These are some notes I wrote back in 2005 that I thought might be interesting here. Looking back at what I was writing at the time, I think I was thinking about nailing these points to a church door somewhere in the company. That actually isn’t a bad analogy as I was advocating a pretty dramatic shift in the role of the kaizen workshop leaders.

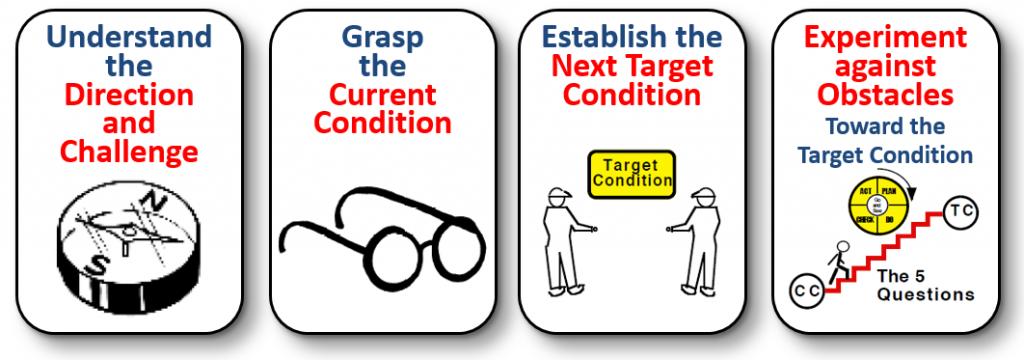

This was written four years before I first encountered Toyota Kata, and reflected my experience as a lean director operating within a $2billion slice of a global manufacturing company. What reading Toyota Kata did for me was (1) solidify what I wrote below, and (2) provided a structure for actually doing it.

Perhaps this will create some discussion. If you are interested in getting a Zoom session together around it, feel free to hit the Contact Mark in the right sidebar (or just click it here) and drop me a note. If there is interest, I’ll put something together.

Kaizen Events

Kaizen events (or whatever we want to call the traditional week-long activity):

- Can be a useful tool when used in the context of an overall plan.

- Are neither necessary nor sufficient to implement [our operating system].1

- There are times when any specific tool is appropriate, and there are no universal tools. Kaizen tools included.

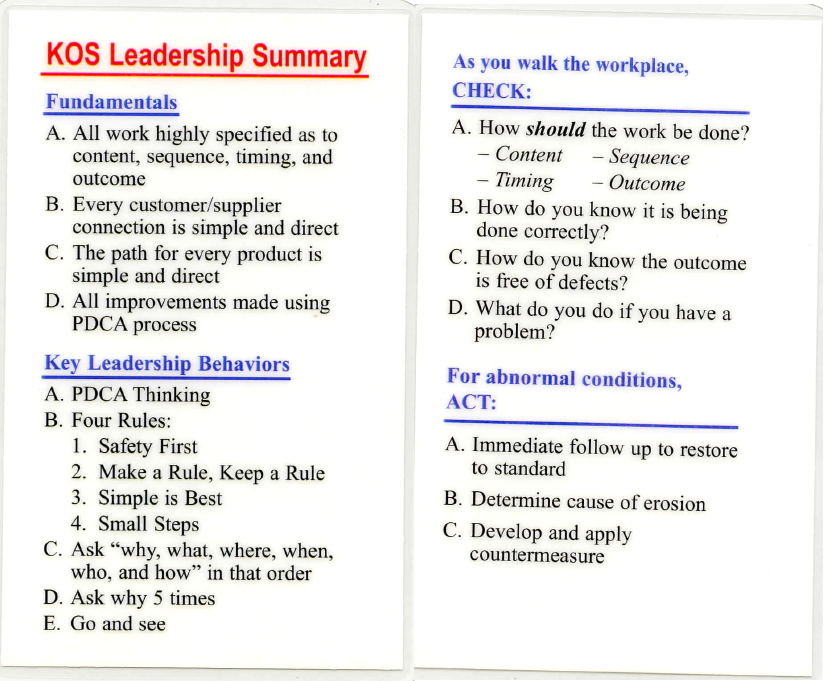

- (Our operating system) is, by our own model, the “Operational Excellence” pillar of (our business system). This is keyed in leadership behavior, not implementation of tools. The tools serve only to provide context for leaders to rapidly see what is happening and the means to immediately respond to problems.

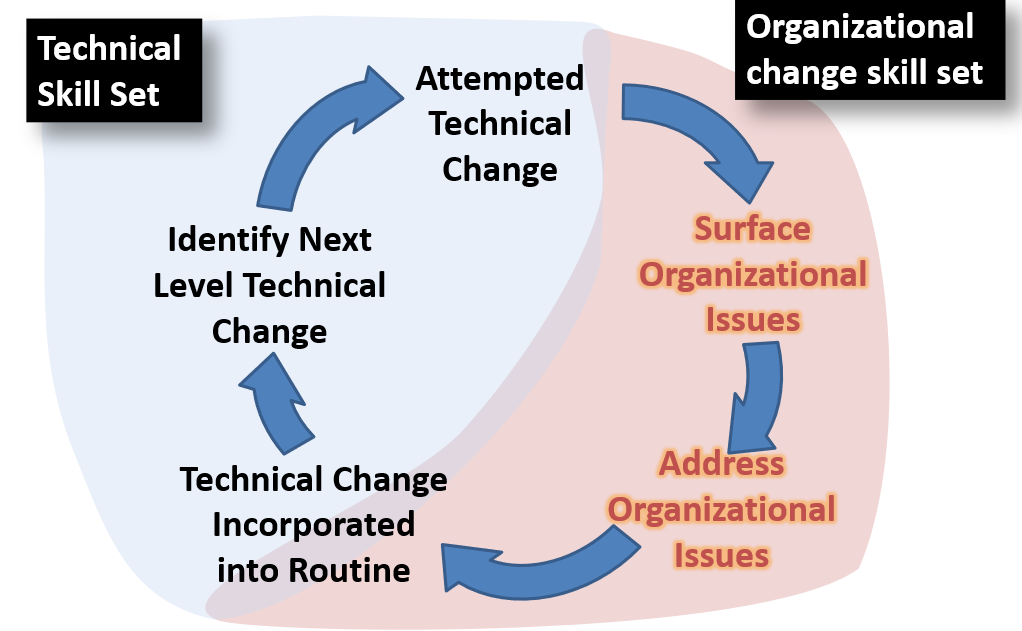

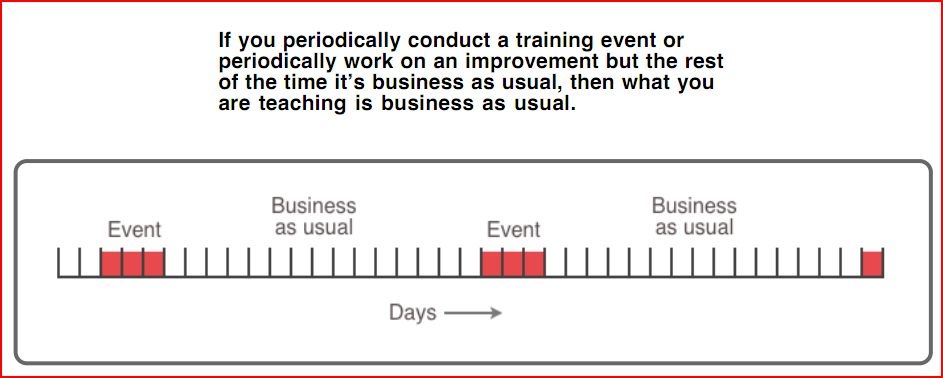

- Thus, focusing on implementing the tools of TPS (takt time, flow, pull, etc) outside of the immediate response and problem solving context is an exercise which expends energy and gains very little sustainable change. This is independent of whether it is done in a week-long intense event or not.

- However, in my experience, organizations which take a deliberate and steady approach implementing have had more success putting the sustaining mechanisms into place. While it is sometimes necessary to bring teams together for a few days at times to solve a specific problem, or to develop a radically different approach, these efforts tend to be more focused than a typical kaizen week I see.

- When the kaizen week is scheduled first, and then the organization looks for what needs improving, this is a symptom of ineffective use of the tool.

- In general, a kaizen, whether it is a week, a month, or even just a few minutes, must be focused on solving specific problems which are impeding flow or are barriers2 to the next level of performance. Without this focus, there is no association with the necessities of the business, and no context for the gains.

- There are a few simple countermeasures which can be applied to a kaizen week activity that focus the participants much more tightly on learning the critical thinking.

Improvement can, and must, take many forms. A week-long kaizen activity is but one. It is expensive, time consuming, disruptive, and should be used deliberately only when simpler approaches have failed to solve the problem.

Classes and Courses ≠ Teaching and Learning

Bluntly, even though we preach PDCA and say we understand it, we are not applying PDCA in our education approach.

Some fundamental tenets:

- All of our teaching should be contextual and focused on what skill or knowledge is required to clear the next barrier to flow or performance.

- The above does not rule out teaching fundamental theory, but fundamental theory must be immediately translated into actions and put into practice or it will never be more than a nice discussion.

- The vast majority of our teaching should be experiential, and based in real-world situations, solving actual problems vs. examples and contrived exercises.

- We want to move our teaching toward an ideal state (a True North in our approach) where it is:

- Socratic – focusing people on the key questions.

- Experiential – learn by application to solve real problems and thus gain experience and confidence that the concepts translate to the real world.

- Thus, education and training is but one tool used by leadership to help people clear the barriers and problems that block progress toward higher levels of performance.

- As far as I can determine, the “Toyota Way” of teaching is similar to this model.

Content

The content of training is as critical as the way it is delivered.

Our objective is to shift people’s thinking, and in doing so, shift their day-to-day behavior as they make operational decisions. The target audience for all of our efforts are the people who make decisions which impact our direction and performance. This is anyone in any position of leadership, at any level of the company – from a Team Leader on the shop floor to the CEO.

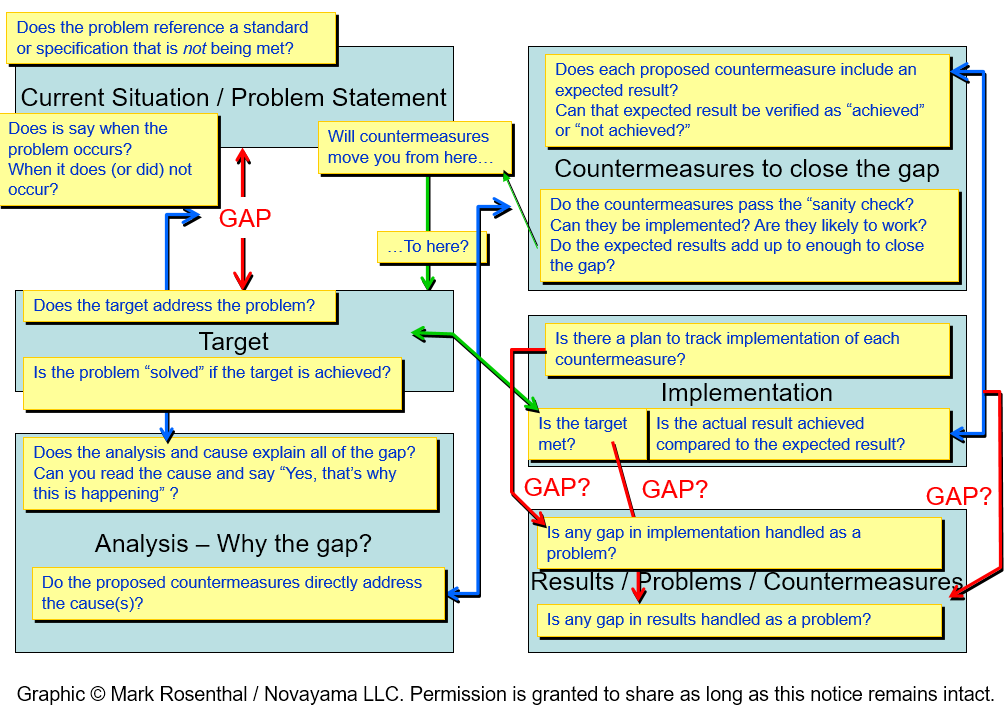

The key is to embed the structure of applying PDCA into all of our content. For example:

- The “rules-in-use” in Steven Spear’s research (Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System and other related publications).

- Every tool, technique, etc. we teach, or should teach, is some application of the above. (The rules-in-use include problem detection, response, and problem solving.) I have yet to encounter an improvement tool or technique that does not fit this model.

- This approach fundamentally re-frames the concept of “problem” and what should be done about it.

- The Toyota Production System (in its pure state) is a process which delivers a continuous stream of problems to be solved to the only component of the system that can think – the people. This is how people are engaged, and this is what makes it a “people based system.” Leave this out, and “people based system” is just hollow words. Nearly every discussion talks about how important people are, but then dives right into technical topics without covering how people are actually engaged — outside the context of a week-long kaizen.

The Role of “Workshop Leaders” in the (Continuous Improvement Office)

No one has disputed the critical make-or-break role played by the line leadership, not only in implementation, but even more so in sustaining.

Workshop leaders are generally taught to plan and lead workshops. The emphasis is on the week-long workshop logistics; on presenting modules in classroom instruction; and on the skills to facilitate a team through the process of making rather dramatic shop floor improvements.

In a typical (not saying it happens here) implementation scenario, it is the workshop leaders who go to the work area, do the observations (usually without a lot of skilled mentoring, and usually just to collect cycle times); build the balance charts and combination sheets; plan what will be changed; how it will be changed, set objectives, targets and boundaries.

They are the most visible leadership of the teams during the week, and they are the ones tracking and pushing follow-up and completion of open kaizen newspaper items.

The effect of this (which is fairly consistent across companies) is:

- The standard work tools are something workshop leaders use during improvement events.

- Cycle times, observations, and looking for improvement opportunities is something that is the domain of the workshop leaders.

- Actually guiding the team members through the problem solving process is the job of the workshop leaders.

- The supervisors and managers are there as team members, in order to learn by participation, from this outside expert.

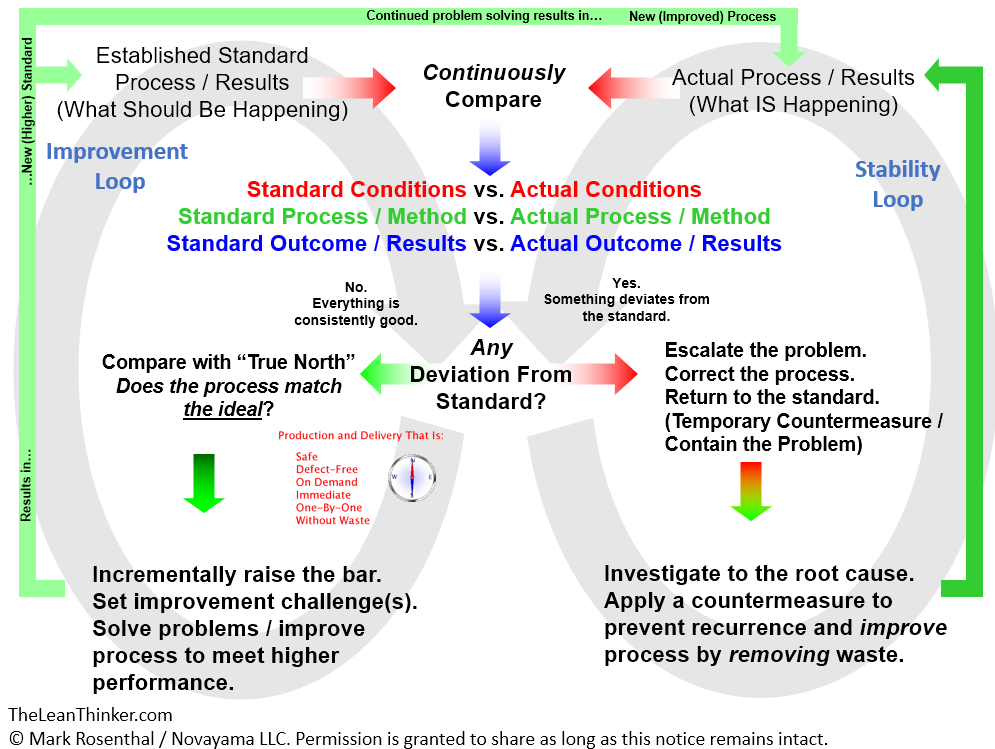

The question is: Who is responsible to coach the line leaders through the process of handling the problems that the TPS is designed to surface in operation?

Once the basic flows are in place, there will be a stream of problems revealed. Those problems will either be seen or not seen. IF problems are seen, they will either be dealt with quickly, following good thinking, or they will be accommodated so they go back to being unseen. This is a critical crossroad for the organization…. and it is the behavior of the first and second line leaders, and the support they get from their leaders, that most influences whether the system backslides or continues to get better and better.

IF problems are seen, they will either be dealt with quickly, following good thinking, or they will be accommodated so they go back to being unseen.

Note: There is not middle ground. One-piece-flow really can’t sustain in a stable state. It is either improving or getting worse. It isn’t designed to stay still, and it won’t. Continuous intervention is required for stability, and that intervention is what improves it.

Who is teaching the leaders to do this?

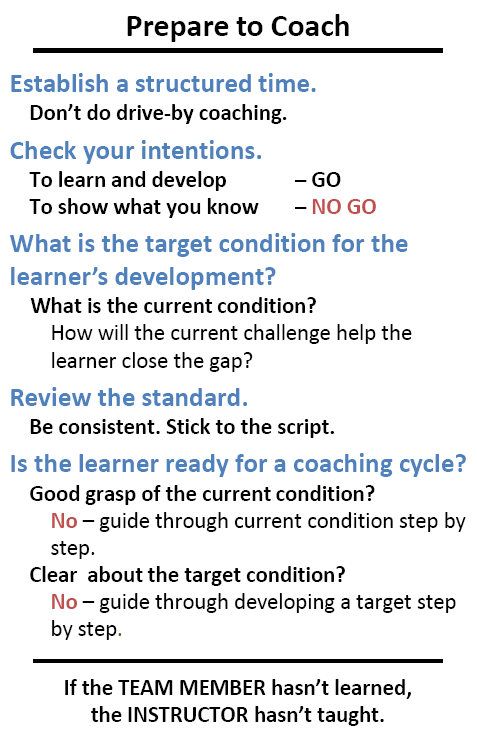

Each leader must have a coach, by name, who can, and will, always challenge his thinking and his solutions to problems against a specific thinking structure.

My view is this is the primary role for the Kaizen Promotion Office.

The way to do this is through application of a few core skills, and skills can be taught.

We should:

- Include this vital role into the expectations of a “workshop leader” – to take them closer to being “coordinators” in the Toyota factory start-up model.

- Provide these “coordinators” with a specific support process so they know that they can quickly get assistance if they feel they are in over their heads.

- The role of that assistance is not to step in and solve the problem. It is to take the opportunity to teach both the workshop leader and the area manager by guiding them through solving the problem.

My experience with this concept is that teaching these skills to someone is not as difficult as most people assume. The basics of observing and seeing flows can be taught over a few days to someone who is motivated to learn. The skill of teaching by asking questions can be accelerated from the “pure” method by telling them what is being done in why. “This isn’t about the answers, it is about learning the questions.”

Application and good teaching can easily be verified by checking the leader’s (the student’s) level of skill and behavior. (The senior teacher checks the teacher by checking the student… just as the area supervisor checks the Team Leader’s teaching by verifying the standard work on the shop floor.

None of this is an advanced topic. These are the basics. Once a good context is established in people’s minds, my experience suggests that the Toyota system is no longer counter-intuitive. The tools and techniques that, at first, seem alien now make sense.

——–

1 By this I meant to shift the operating culture to one that inherently supports continuous improvement.

2 In Toyota Kata language, we would say “obstacles.” I had used the term “barriers” up to that point.