The team was driving toward a consistently executed changeover process as a target condition.

In the last iteration, the process was disrupted by a scrapped first-run part. The initial level cause was an oversize bit in the NC router resulting in an out-of-spec trim and oversize holes.

This occurred in spite of the fact that there are standard tools that are supposed to be in standard locations in the tool holders on the back of the work pallet.

Upon investigation, the team found:

- The previous part had a programming error calling out the oversize tool from the wrong location.

- All of the operators were aware of this, and routinely replaced the “standard” tool with the one the program required.

- After that part was run, the standard condition had not been restored.

- There was likely a break in continuity between operators here, but that was less clear.

- The two bits are only 1/8 different, and hard to distinguish from one another across the 10 feet or so of the work pallet.

The team addressed the programming error, but among the thousands of other programs out there, they were reasonably certain that there were other cases where the same situation could be set up.

They wanted to ensure that it was very clear when there were non-standard tools in the standard locations.

Their initial approach was to create a large chart that called out which tools were to be in which holders. Their next experiment was to be to put that chart up in the work area.

“What do you expect to happen?”

That turned out to be a very powerful question. After a bit of questioning, they implied that the operator was to verify that the correct tools were in the standard positions before proceeding.

“How does this chart help them do that?”

They can see what the standard is.

“Don’t they all already know what the standard is?”

Yes…..

“So how does this chart help them do that?”

Now, to be clear, the conversation was not quite this scripted, but you are getting the idea. The point was to get them to be specific about what they expected the operator to do, and to be specific about how they expected their countermeasure to help the operator do it.

One team member offered up that maybe they could color-code the standard tools and their holders so it would be easy to check and easy to see if something was off-standard. That way, even IF the situation came up where the operator needed to deviate from the standard, anyone could easily see what was happening.

(I should add that they have already put an escalation process into place that should trap, and correct, these programming errors as they come up as well.)

The tools were color-coded over night, and in place the next day.

This wasn’t a “5S campaign,” nor is there an audit sheet that tries to measure the “level” of visual control in the work space.

Rather, this is using a visual control to visually control something, and reduce the likelihood of another scrapped part (and therefore, disrupted changeover).

Over the last week, the work cell has been improving. When things are flowing as they are supposed to, changeovers are routinely being done within the expected time.

But there are times when their standard WIP goes low; there are times when someone gets called away; when the flow doesn’t go as planned. When those things happen, they get off their standard.

The next countermeasure is to document, clearly, the normal pattern for who works where, for what inventory is where. Then the next question is “How can anyone verify, at a glance, whether or not the flow is running to the normal pattern?”

More visual controls. Ah.

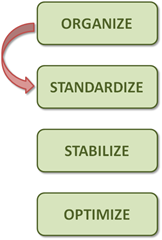

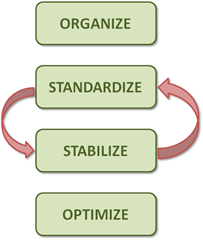

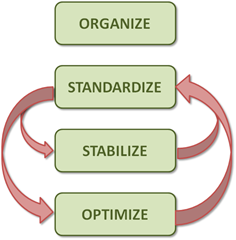

Now we are seeing the reason behind 5S. It will come in to that work area, step by step, as the necessity to make things more clear arises.

![]()