27 months ago I wrote a piece about a “firefighting culture” where I described the actual process used to fight fires – following PDCA.

I have learned a few things since then, and I want to tighten my analogy a bit.

What is the core thinking behind true firefighting? This is actually closer to home than you may think. Many companies have situations that are on fire – in that they are destructively out of control.

I recall Mr. Iwata lecturing a group of managers in a large aerospace company in Seattle. He listened patiently to their grand plans about how the transformed operation would look. Then his remarks cut to the chase.

“Your house is on fire. This is not the time to be thinking about how you will decorate it.”

The question is – does urgency force a change in the thinking or approach?

I say it does not. However urgency does stress people’s skills and capabilities to deal with the situation to the limit – and beyond. Thus, it is best if those skills are thoroughly developed before there is a crisis, when the stakes are not so high. This is how high-risk professions train. They work to develop ingrained habits and skills for handling chaos before it is real.

So let’s go to our hypothetical burning building and look at what happens – as a matter of routine – even though every situation is different.

The target condition is a generally a given: The fire is extinguished, things are cooled down enough that there will be no re-ignition.

What is the current condition? Yes, the building is on fire. (doh!) But there is more to it than that.

What is stopping us from putting this fire out right now?

What is the layout of the building? Its construction? Where are the air shafts, sources of fuel, oxygen? Are there hazards in the building? Is there a basement under the main floor? Is there anyone inside?

Because they are (hopefully) skilled and practiced, gaining this information is routine, and hopefully they are getting most of it on the way.

The fire chief on site is going to develop an overall strategy for attacking the fire, and deploy his forces accordingly.

One thing they do not do – they don’t go creating action item lists, they don’t go hunting for fires, and they don’t just go into reaction mode.

Neither do they have a detailed “action plan” that they can blindly follow. Simply put, they are in an vague situation with many things that are still not known. These things will only be revealed as they progress.

What is the first problem?

The initial actions will be more or less routine things that help the effort, and gain more information. They are going to ventilate the roof to clear smoke, and they are going to first work to rescue any people who are trapped.

This is their initial tactical target condition.

As they move toward that target, they will simultaneously gain more knowledge about the situation, decide the next objective, and the actions required to achieve it.

Cycle PDCA

As they carry out those actions, either things will work as predicted, and the objective will be achieved or (more likely) there will be surprises. Those surprises are not failures, rather they are additional information, things that were not previously understood.

Because this is dangerous work, if things get totally strange, they are going to back-out and reassess, and possibly start over.

As they go, they will work methodically but quickly, step by step, never leaving fire (unsolved problems) behind them, always having an escape path.

And, at some point along the way, what must be done to accomplish the original objective, put out the last of the fire will be come apparent.

Why are they so good at this?

Simple. They practice these things all of the time, under constant critical eyes of trainers. Every error and mistake is called out, corrected, and the action is repeated until they routinely get it right. Even though they are very good at what they do, they know two things:

- They can get better.

- Their skills are perishable.

So, although each fire is different, they have kata that they practice, continuously – from basic drills to training in more complex scenarios. They are putting these things to use now that there is real urgency.

What about the rest of us?

In business, we tend to assume that crisis will either not occur, or when it does will be within our domain of being able to handle it… but we often get surprised and our problem solving skills are stretched to the breaking point.

Why?

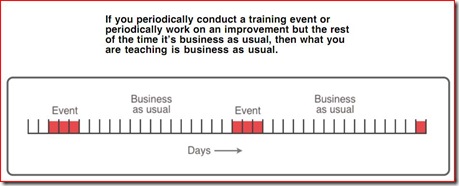

Because we have never really practiced those skills, and if we have, we have not been critical enough of how we went about solving routine problems, and we are sloppy.

When there is no urgency, we can get away with being sloppy. When method is not critical, anything more or less works. But when things are complicated, messy, and right now, there isn’t time to practice. “You go to war with what you’ve got.” What that really means is that, however ill-prepared you are, you now have to deal with reality.

Problem solving is as important to a business (and I include any human enterprise, profit or not in this) as it is to the firefighters. Business has technical skills, as firefighters have handling hoses, operating their equipment, etc. But no matter how competent firefighters are at their technical tools, they are lousy firefighters if they have not practiced quickly solving problems related to putting out fires.

Likewise, no matter how good you are at keeping your books straight, managing your order base, scheduling production, whatever routine things you do, if you have not practiced problem solving skills on a daily basis, you are likely not very good at it. Daily kaizen is practice solving problems. The side-benefit is your business gets better as a result.

The difference is that firefighters know it is important, so they practice, subject themselves to the critical eye of professional trainers and coaches. In business, nobody teaches “problem solving” except in the most vague way.

“All we do is fight fires.”

Hopefully you wish you were that good.