I have been touting Chip and Dan Heath’s book Switch for some time now, so it I thought I ought to actually write about why.

I have been touting Chip and Dan Heath’s book Switch for some time now, so it I thought I ought to actually write about why.

If you are in the role of a “change agent” this book is your manual.

Up to this point, the bible for “organizational change” has been John P. Kotter’s book Leading Change published by the Harvard Business School.

Based on his article Eight Reasons Why Transformation Efforts Fail, Kotter outlines (not surprisingly) an eight stage process for changing a culture:

- Establish a sense of urgency.

- Create the guiding coalition.

- Developing a vision and strategy.

- Communicating the change vision.

- Empowering employees for broad based action.

- Generating short term wins.

- Consolidating gains and producing more change.

- Anchoring new approaches in the culture.

I have found it quite valuable in the past to challenge a leadership team to assess their own efforts against these factors, then listen to what the next level down has to say. There is always a large gap – what the leaders THINK they are saying clearly is much more muddled to the listeners.

Chip and Dan Heath take things down another couple of levels. They deal with the psychology – what goes on between our ears, and their process maps very well back to Kotter’s – as a much more explicit “how to.”

The Psychology of Continuous Improvement

What really hooked me into this book, though, was just how well it maps to key characteristics of a Toyota-style management system.

People in companies that are exceptionally successful with continuous improvement have the same baseline thinking patterns as people in every other company out there.

The difference is not about hiring different people, it is about how the work and the environment itself is structured. It is likely that structure wasn’t deliberate, these outlier companies just stumbled into it. But if we look at what makes them different (see “Find the Bright Spots” below), we can see they are better at dealing with the things outlined in this book.

That, to me, is encouraging because it reinforces the idea that true operational excellence is within the reach of anyone who is willing to deal with the real issues.

And – key point here – these changes are within the power of the mid-level change agent to affect. You don’t have to be “top management” or even in charge to have an impact. (You do have to work harder and more explicitly, though.)

We (like to) Think It’s About Logic – But It Isn’t.

In business we operate on the assumption that decisions are based on objective, rational analysis of facts and data. If presented with a compelling case, we say, the logical conclusion should follow.

So our efforts to enact “change” start, first and foremost, with trying to educate so that people will “understand the changes” and the “reasons why.”

If they don’t get it, we think, it is because they don’t understand the goodness, so we need to explain it better.

This thinking drives us to try to construct more compelling models and representations of “the system” in our effort to explain why it is better.

If we address the emotional aspect at all, it is usually with trying to “create a crisis” or a “burning platform” – in other words, using fear as a motivator. Or, even worse (apparently), we try incentives to manipulate behavior.

Switch uses a metaphor of the human psyche that is borrowed from Johnathan Haidt’s work in The Happiness Hypothesis.

Switch uses a metaphor of the human psyche that is borrowed from Johnathan Haidt’s work in The Happiness Hypothesis.

Haight constructs a metaphor of our mind as an elephant, representing our emotional responses, and a rider on the elephant, representing the logical and rational side of our mind.

You can quickly get the idea here – the rider can influence where the elephant goes, but that’s about it. Unless the elephant feels safe going there, and trusts the rider’s judgment, it ain’t gonna happen.

Following that metaphor, Heath and Heath outline nine actions that shape how groups (and individuals) respond to changes. The book describes them in detail, with stories, examples, and structure.

Online, they have the Switch Workbook which provides a great quick-reference for the book. I highly suggest reading the book rather than trying to use the workbook as a substitute, though. Otherwise you lose a lot of context.

The overview and comments below are organized the way the key points are covered in the workbook.

Direct the Rider

Our metaphorical elephant rider is busy and stresses easily. Given too many choices, the rider becomes paralyzed and takes no action at all.

This is what happens, I think, when we present tons of general, theoretical education and then expect team members to pick up their own initiative and “improve things.”

So it is necessary to provide enough structure to allow people to focus their attention on “how to do it” rather than “what to do.” This means being far more explicit than we typically are. “Vision” is not an ethereal saying on the wall. It is a concrete description of how we want the organization to work.

In this category, Heath & Heath cover three key points that address the logical approach:

1. Find the Bright Spots

Rather than focusing on what isn’t working and trying to fix it, go find examples of where things are working and try to understand why – what makes them different.

Often there are one or two key factors involved and, once understood, they are fairly easy to educate and replicate.

Of course, to understand what makes them different, you must also understand the normal way things are done, and compare that with what you find in the positive outliers.

If I were to use Toyota-style language, I would say “understand the current condition” and use the positive outliers as the basis for a target. Then look, at a detailed level, at what small things make such a big difference. This is a classic “is / is not” analysis, but applied rather than just theoretical.

2. Script the Critical Moves

The most common theme of frustrations I hear from change agents and practitioners has to do with people “not supporting the changes.” But when I question them about what they WANT people to do, I often get a list of abstractions.

To make things even more interesting, many of us (myself included) have been taught to focus on the physical process changes rather than the behaviors required in a continuous improvement culture.

From the Switch Workbook on the Heath Brother’s web site:

Be clear about how how people should act.

This is one of the hardest – and most important – parts of the framework. As a leader, you’re going to be tempted to tell your people things like: “Be more innovative!” “Treat the customer with white-glove service!” “Give better feedback to your people!” But you can’t stop there. Remember the child abuse study [from the book]? Do you think those parents would have changed if the therapists had said, “Be more loving parents!” Of course not. Look for the behaviors.

Another common source of frustration among practitioners is the comparison with perfection. Now there is nothing wrong with this. It is actually how we should think. But there is a difference between using perfection as your benchmark and expecting it to be achieved in one fell swoop.

By setting a limited theme that you know will advance the process, you help people focus on specific actions – you script what they should be working on, and give them permission to not try to fix everything at once.

One good way to test a theme or critical move is to ask whether or not it is “sticky.”

The other thing that helps, according to the workbook, is keeping the change within the scope of how people think about themselves. It is far easier to reinforce behavior that fits in with an existing self-image than to try to change something so fundamental.

3. Point To The Destination

Do you have a tangible objective that is “met” or “not met?”

What happens in too many “lean implementations” is that the process itself is the objective. “We want to be a lean company.”

So what?

“OK, we want all of our materials on a pull system.”

So? Why?

“We want zero parts shortages.”

Ah! That is something you can rally people around.

At the same time, avoid abstract metric targets. “Gross margin” or “inventory turns” targets might be OK in the board room, but in the real world (which, unfortunately, rarely extends into a board room), you need something tangible that people can see and experience.

Motivate the Elephant

The next three items come under the heading “Motivate the Elephant.” The elephant is the metaphor for our emotional responses to things. As much as the business world likes things to be sterile and logical, people never work that way.

Our logical decisions always follow emotional decisions. If there is a misalignment between the two, we feel great anxiety. Haidt describes “the rider” (our logical mind) as a skilled attorney who can construct a logical, sound rationale for any actions that the elephant takes.

So, where “the rider” can be paralyzed by too many options, “the elephant” needs to feel it is safe to go where the rider is trying to take him.

4. Find the Feeling

Taiichi Ohno talked a lot about waste. He described wasteful actions in ways that made it easy to see. His point, I think, was to give his managers a clear picture of just how much opportunity there was, if only they worked to make things flow.

As a sidebar, I don’t believe he made TPS about “eliminating waste” per se. He doesn’t talk about it much once he makes the initial point. Different topic.

The idea of concentrating your effort into a small model area (rather than trying to take everyone along at once) fits into this. It shows people, in a tangible way, what is possible.

The principle of “go and see for yourself” makes the current condition (and the possibilities) real to people in ways that the best PowerPoint presentation never can.

The key is to acknowledge that “rational analysis of facts and data” rarely (if ever) evokes the kinds of things that cause change.

5. Shrink the Change

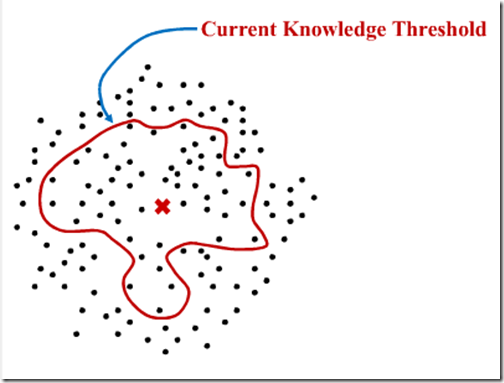

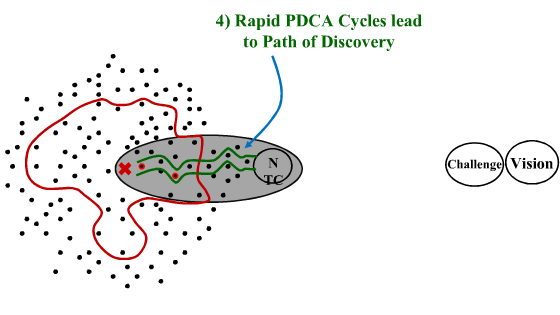

When I read this chapter, I saw an immediate correlation with the process of rapid coaching cycles and target conditions that Mike Rother describes Toyota Kata. Aside from driving continuous improvement, that process seems to be almost engineered to shift the culture.

This might seem contradictory with “Find the Feeling” but Big Change overwhelms people – it scares the elephant. So while it is important to have a compelling sense of destination, it is equally (if not more) important to have a sense of immediate progress – “we are getting somewhere.”

In the book, the authors give a couple of great examples. In one, they outline an experiment with customer loyalty cards for a car wash. Two groups of customers were given loyalty cards.

One group required 10 stamps to get a free car wash.

The other group required 12 stamps to get a free car wash – but they were given two free stamps to start with.

Thus, each group actually had the same distance to the goal. But the response was significantly higher for the second group. Why? Because they started with a sense of investment. They had runway behind them, which made the distance to close seem shorter.

The two free stamps also gave them a sense that they would be “wasting” or “losing” something of value if they didn’t go ahead and complete the card.

When we look at an area for improvement, do we focus on how bad it is, or do we frame our next steps to honor the work they have already done and work to build on it? We are going to be doing the same work either way, this is a matter of presentation.

At the same time, do we try for the “big leap” and the 80% reduction as the goal, or do we set a series or more modest objectives that anchor a sense of success and moving forward?

Do you structure a big, complex “lean implementation plan” or do you take on one value stream loop at a time?

6. Grow Your People

Humans are incredibly social. We want to feel we are part of a group. We want a group identity that we can share.

Can you cultivate that sense of group identity in a way that aligns people in the direction of the changed behavior? What sense of identity already exists?

At the same time, you can strengthen people’s resolve in the face of obstacles by predicting them.

“When we implement flow, we are going to see a lot of problems come to the surface.” By warning people in advance about what to expect, you can shift the response from being discouraged to accepting the challenge of solving those problems one by one – because those problems tell us “This is working” rather than “it isn’t working.”

If you can challenge people to embrace what Heath and Heath call “the growth mindset” – we are going to build out competency by practice, which means failing and learning sometimes – that helps turn a surprise or disappointing result into a challenge to learn and grow.

Shape the Path

This is, in my opinion, an area where we make the biggest mistakes. A lot of efforts to implement start off with a “lean overview” of some kind – even to the top leaders – and then leaves it up to them to decide how to go about implementing all of this.

But they are still operating in the same environment they always have, and no matter how compelling the vision, there are obstacles in the way. The path is not clear.

The last three actions cover how to structure the process, the environment, even the organization in ways that clear the path you want people to follow.

7. Tweak the Environment

As I was reading these examples, I was getting really excited because it was all familiar. But Switch was adding even more weight behind the things that we do under the name of “kaizen.”

Yes, we are stabilizing and improving the process, but we are also clearing the path toward the behavior we want.

Consider these two examples from the workbook:

Do a “motion study.”

If you’re trying to make a behavior easier, study it. Watch one person go through the process of making a purchase, filing a complaint, recycling an object, etc. Note where there are bottlenecks and where they get stuck. Then try to rearrange the environment to remove those obstacles. Provide signposts that show people which way to turn (or celebrate the progress they’ve made already). Eliminate steps. Shape the path.

If this doesn’t sound familiar to you as a kaizen practitioner, you need to dig out the basics. This is not only exactly what we should be doing every day, it is exactly what we should be teaching others to do as well.

TPS / “Lean” is a management system that strives to do this every day. The cool thing, in my mind, is that Switch is as much describing what should be our routine as it is describing how to change the routine.

Or try this example:

Can you run the McDonalds playbook?

Think of the way McDonalds designs its environment so that its employees can deliver food with incredible consistency, despite a lack of work experience (or an excess of motivation). They pay obsessive attention to every step of the process. The ketchup dispenser, for instance, isn’t like the one in your fridge. It has a plunger on top that, when pressed, delivers precisely the right amount of ketchup for one burger. That way, if you have to deliver 10 burgers in a minute, you don’t have to think at all. You just press the plunger 10 times. Have you looked at your own operations through that lens? Have you made every step as easy as possible on your employees?

Here is where the nay-sayers tell us “But that work environment gives people no sense of creativity.” Damn right. I don’t want any creativity around the way the product is made. I want to know that my customers are going to get exactly what was specified.

The opportunity for creativity comes from challenging people to create a work environment that makes it easy to consistently deliver the product. And there are endless opportunities to do this. If / when quality is perfect, then work on productivity.

So as we work to “tweak the environment” the real question for a lean practitioner is how to structure things that make and hold space for this creative process of improvement to happen. What blocks the path? Have you carved out that space, or do you expect people to just find a way to do it?

And finally, Heath and Heath challenge us to look at the environment before we start blaming people. Good people working in a bad environment are often painted as flawed in some way. This is called “attribution error” – attributing bad results to the person rather than the process. I have yet to meet anyone (myself included) who was not guilty of this now and then.

The people we call the “anchor draggers” and “cement heads” are making the best decisions they can in good faith, based on the environment and information that surrounds them. We have an opportunity to shape that environment, and thus alter the inputs they deal with.

8. Build Habits

“Behavior” is built up from how people respond to the things around them that trigger those responses. When we talk about “habits” we are really talking about consistent responses or actions.

If we want to change those responses, it is helpful to link the new response to a specific trigger.

Again, looking at a TPS environment, I immediately think “andon.” There is a specific trigger (the light is ON or OFF) and a specific response.

Digging in deeper, and looking at the work Steven Spear did in his original research (which is summarized in Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System) we see an environment that is precisely structured to provide explicit triggers for explicit actions.

Further, there are processes to verify that what was expected is what happened, and any deviation triggers another specified response. So I see yet another area where the Toyota management structure is engineered to provide the kind of environment that Switch talks about.

If I am trying to alter behavior, I ask the same questions. Can I set a specific trigger that calls for a specific action that I can check?

Can I take something that people already do and structure the work (“tweak the environment”) so that routine action triggers the new behavior?

Can I structure the work to sequentially cue the next process step as each is accomplished?

9. Rally the Herd

And finally is reinforcing, again, the fact that humans are naturally biased toward wanting to be part of a common social structure.

What is the prevailing social pressure in the organization? Is it counter to what you are trying to do? Are the people who are adopting the new behavior isolated from one another? Are you trying to spread the early adopters too thin, in the hope that they will inoculate the rest of the organization? They will inoculate the organization – by creating powerful antibodies against the change. Small, isolated efforts dissipate your resources to the point where they are ineffective.

What can you do to create a majority from the minority? This is one benefit of the model line. It establishes a concentrated environment where everyone is focused on the same thing, and eliminates (or at least reduces) the social pressure against the new behavior. “We are in this together.”

Now, having a model line does not guarantee that the rest of the organization will spontaneously adopt the new way. Far from it. It takes deliberate action.

“Rally the herd” also means that the group that is doing what you want are celebrated as “doing it right.” But you have to do this in a way that doesn’t rub people the wrong way. Believe me, I’ve seen with my own eyes the pushback created when one division of a large company was constantly lauded as the “shining star” to the others.

Nevertheless, you want to highlight the bright spots, and then find specific, small things that have made a difference. GM couldn’t “just be more like Toyota” or “more like NUMMI.” That wasn’t enough. They wanted the results, but apparently never dig in to truly understand the few key things that went deeper than the mechanics.

Conclusions

Practitioners are often expected to “drive the change” into an otherwise passive-aggressive organizational culture. This can be a frustrating experience because lean practitioners are rarely given the tools to affect social conventions.

It is a sad fact that the vast majority of efforts to “implement lean” falter or fail within a few years. The message that I draw from this is “Look at what most people are doing, and do something different.” The mainstream message we have been getting doesn’t work very well, and just “trying harder” is no more effective here than anywhere else.

This book, with some careful study, discussion, and a little collusion, can form a great blueprint for how to actually structure your work to move the cultural change along.

The key is to remember that the “lean implementation plan” is NOT about how to implement takt, flow and pull. It is a plan to shift how people behave and respond to issues every day. The tools are important, but only because they create opportunities for people to learn and demonstrate the new way of daily management.

![]()