The spring and summer of 2000 were a long time ago, but I learned some lessons during those months that have stayed with me. In fact, the learning from that experience is still happening as I continue to connect it to things I see today.

I was a member of a team working hard to stand up a new production line of a new product. The rate pressures were very high, the production, production control, and quality processes were immature.

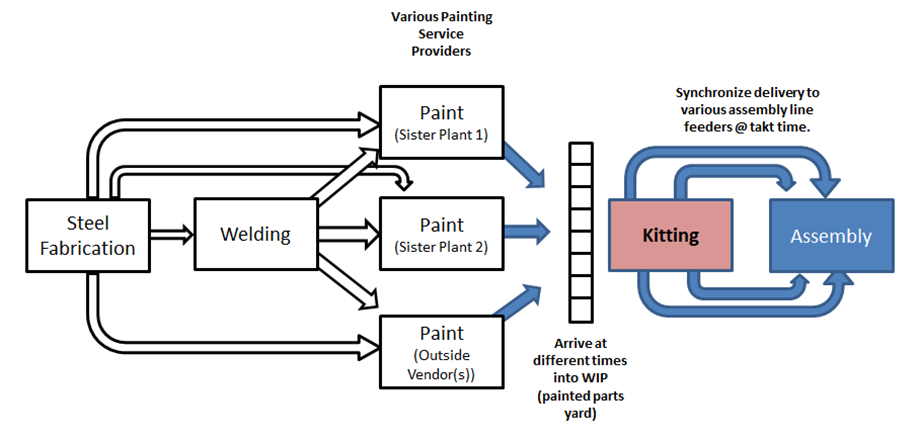

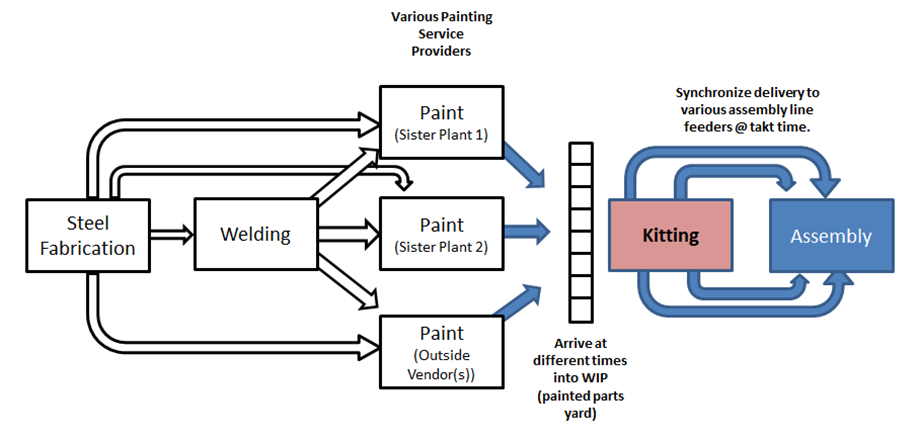

At a high level, the parts flow was supposed to work like this:

Steel parts are fabricated and welded, based on the production schedule for various configurations.

Unit sets of parts were sent to outside paint. (We didn’t have our own paint system yet.) In reality, unit sets would be broken up as some parts went to sister plants, others went to outside vendors, each with their own lead times and flow times.

Parts return from outside paint. Because of the different vendors and lead times, different parts arrive on different days.

On assembly day, kits are built for the parts required at each entry point on the assembly line. Those kits are delivered based on a pull. The assembly line had a number of entry points and feeders, so for each takt time cycle, though only one “unit’s worth” of parts were actually delivered, those parts were for different units, as feeders had different lead times into the main line.

The innocuous challenge was to develop the kitting process (in red) that broke down the parts into kits and got them delivered to the line.

I got pulled in on Thursday of a “kaizen event” that was supposed to develop this process. What had actually happened, though, was analysis paralysis, a lot of theoretical discussions, a lot of drawings on a white board, but nothing had actually been tested or tried. My assignment was simple: Organize this and get it going on Monday.

I had four people working for me, though they were not officially direct reports. They were an eclectic mix of personalities and styles.

A few things became apparent very quickly:

The process of scheduling which parts needed to be fabricated and welded to be sent through painting on any particular day was broken. Result: What was needed wasn’t necessarily what got sent to paint.

The processes of keeping parts organized during the various outside paint operations was broken. Result: Unit sets got mixed together, parts went missing.

As a result this is what my days looked like:

I came in before a hint of dawn at 4:45am to prepare for the assembly line starting at 5:40. I would go out into the parts yard with the day’s production schedule and a flashlight. My goal was to answer a simple question:

What units on this list can I build with the parts that are here?

I would re-sequence the production schedule to front-load the units that looked like we had everything we needed. (This caused all kinds of problems with serial number sequences and engineering change control, but that is a different story.)

We would start pulling in those parts, and breaking them down into the kits. We set up FIFO lanes for each entry point on the assembly line, and worked as fast as we could to build up about a three hour backlog. Why? Because it took about three hours to expedite a missing part through paint. Once we had that queue built up, as we discovered shortages (or parts painted the wrong color!), we had a chance to get the situation corrected and have a shot at not creating a shortage on the line.

We were working 10 hour shifts, I was typically there for 12-14 hours. Even though I was a “lean guy” my daily work was orchestrating all of this chaos, expediting and delivering parts, and I spent at least six of those hours every day driving a forklift. I got really good at forktruck operation that summer.

At the end of the day, I might sit and chill for a little while, then would get in my truck, go home, and do it all again tomorrow. One of those days as I went to back out of the parking space, I hit the turn signal to put my stick-shift truck into reverse – because that’s how the forklift controls worked.

What I Learned

I actually continue to learn. But here are a few things that have stood out for me.

Shop Floor Production Supervisor is a really hard job. I wasn’t a supervisor, but I was doing many of the things that we asked supervisors to do. Making my people take their breaks. Slow down on the pallet jack. Listening to a frustrated guy who was ready to quit – understanding his paradigm, and helping him re-frame his experience. Constant radio calls to places in whatever building I wasn’t in at the time. Operating within a system that functions only with continuous intervention.

I totally knew how to set up a workable, stable process. I knew how to get all of these processes linked together to pull everything through. I knew how to build in effective quality checks.

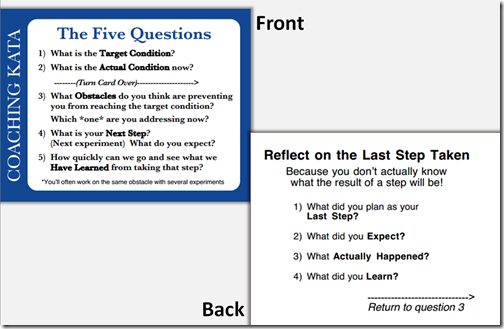

What I was able to do was spend a few minutes at the end of my day, or during my lunch breaks (instead of eating) trying to implement some kind of simple visual control that mitigated against repeating a mistake we had just made. We attached a tag with a production sequence number (000 through 999, repeating) to each kit. That let us, and the people on the line, see if we had delivered something out of sequence.

Then, after I had delivered a yellow painted kit to go onto an otherwise blue painted unit (oops) we made a board with the production sequence numbers and the associated colors for the major components.

Then… after I had delivered (note the theme here) the wrong size of a major component to the line, we added that information to the board AND tagged those components so we could quickly distinguish one from the other.

But I was never able to address the upstream issues that were delivering short kits to us in the first place. All I could do was add steps, add time, add inventory to protect myself from those things and do my best to fix it before the main line got stopped.

We had a saying in the Army: “When you are up to your a$$ in alligators, it is hard to work on finding the best way to drain the swamp.”

Thus:

It is unreasonable to expect systems improvements when everyone is scrambling to make the system function at all. It isn’t that they don’t want to make improvements. It isn’t that they don’t know what to do. It is that there is barely time to breathe before the next problem needs to be stamped down.

And finally: A five person job requires five people. I had four people working for me. That wasn’t enough. Guess who had to fill in the rest of it? I tried my best to handle the problems so they could get into some kind of cadence on the stuff that wasn’t a problem. But (Routine+Problems) = (or greater than) 5 people in this case, and it took all of us just to navigate the rapids without dumping everyone out of the boat. If everything was running smoothly, it was probably a three person job. If we could have set up a sequenced pull from assembly all the way back through weld, it would have been a two or even one person job.

Reflection

That forklift key is still on the keyring in my pocket as a reminder of that time. What follows are some of the bigger-picture things that come to mind as I continue to construct, tear down and reconstruct my own thinking.

Attribution Error

There is a strong tendency among us humans to attribute our own failures to a poor environment, but to attribute other’s failings to individual character or capability. Yet in many cases, simply changing the venue or circumstances can allow a previously low-performer to blossom. We see this (and the opposite) all of the time in professional athletics.

Making this error is easy when we are talking about “they.” If only they… Why don’t they… They don’t get it… “They” are people who are likely doing the very best they can within the context of the system they are in. And, as I pointed out above, changing the system from the inside is hard.

Actually that isn’t quite accurate. Changing the system is hard work.

The Pace of Change

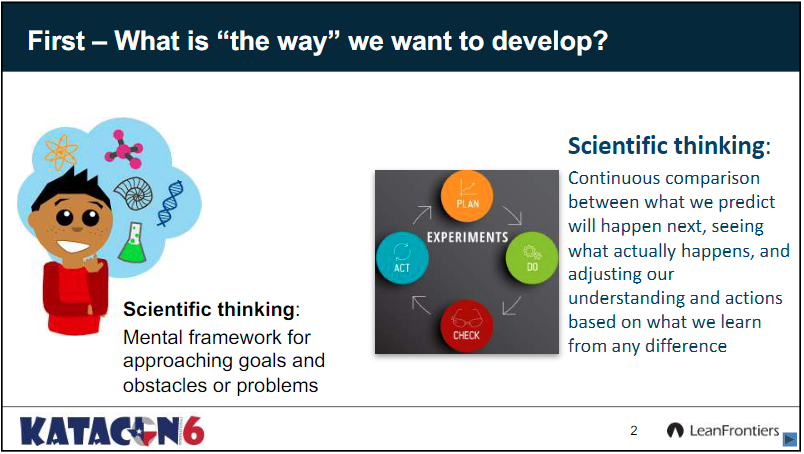

The organization I was describing above was experiencing circumstances at the time that outpaced their ability to experiment, reflect, and adapt. Every organization has a rate at which they are able to change.

Just to make things more complicated, it is possible to learn what must be done much faster than those things can be put into place. This frustrates a lot of change agents. They see the technical changes that must take place, but often struggle against cultural barriers and obstacles. These things take much longer, and it is pretty much impossible to put them on a fixed timeline or project plan. Thus, we frame them as “resistance to change.” We know what must be done, but “they” don’t do it.

Organizations Under Stress

When an organization is under stress, there is fear of complete breakdown. People become very conservative and avoid the uncertain and unfamiliar. If they become overwhelmed just trying to get their task done, they are going to shut out any information that isn’t relevant right now. Horizontal communications break down, and the feeling of isolation increases.

At this point, all coordination has to funnel upward and then downward through the vertical linkages, as cross-functional coordination largely isn’t happening.

Now the higher leader gets overwhelmed, feeling she has to micro-manage every detail- because she does. “Why don’t they talk to each other?” Well, the structures for that were probably very informal, and now have broken down.

This Isn’t About “Them”

As I mentioned above, it is really easy to attribute the perception of dysfunction to individuals. And as people become isolated within their own task-worlds, avoiding a mistake becomes the dominate motivation. This happens even in organizations with the most benign intentions.

If you are a leader, pay attention to the emotions. If people are snippy, are pushing back on ideas as “just more work” then that saturation point may well have been reached. Pushing harder isn’t going to make things go faster, it is going to slow them down.