Note – this post was written pretty much simultaneously with a post on the lean.org forum.

Mike Rother has put up a compelling presentation that highlights a long-standing misunderstanding about the purpose of “standards.”

Some time ago, a (well-meaning) author or consultant constructed a graphic that shows the PDCA wheel rolling up the incline of improvement. There is a wedge labeled “Standards” shoved as a chock block under the wheel to keep it from rolling back. That graphic has been copied many times over the years, and shows up in nearly every presentation about PDCA or standard work.

The implication – at least as interpreted by most – is that a process is changed for the better, a new standard is created, and people are expected to follow the standard to “hold the gains” while they work on rolling the PDCA wheel up to the next level on the ramp.

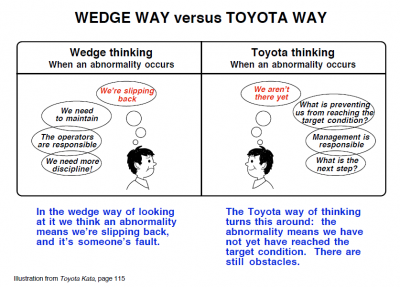

Slide 6 (taken from the book Toyota Kata) shows the underlying assumptions that are implied by this approach, especially when it doesn’t work.

There are some interesting assumptions embedded in the “wedge thinking.”

There are some interesting assumptions embedded in the “wedge thinking.”

The first one is that “the standard can be ‘held’ by the people doing the work.

That, in turn, means that if when things start to deteriorate, the workers and first line leaders are somehow responsible for the “slippage” or “not supporting the changes.”

With this attitude, we hear things like “Our workers aren’t disciplined enough” or “How do I make them follow the standard?” The logical countermeasures are those associated with compliance – audits focused on compliance, and sometimes even escalating punitive actions.

Back in my early days, I had a shop floor team member call us on it quite well: “How can you expect us to hold some kind of standard work if the parts don’t fit?” (or aren’t here, or the tools don’t work, or jigs are misaligned, or the machine isn’t running right, or someone is absent, or we are being told to hurry and just get stuff out the door?)

This is the approach of control. The standard is fixed until we decide to change it.

Taiichi Ohno didn’t teach it this way.

Neither did Deming or Juran. Neither did Goldratt. Nor does Six Sigma, TQM, TPM.

Indeed, if we want creativity to be focused on improvements, we have to look up the incline, not back.

We are putting “standards” on the wrong side of the wheel. Rother’s presentation gets it right – the “standards” are the target – what we are striving to achieve.

The purpose of standards is to compare what we actually do against what we wanted to do so we know when they are different and so we have some idea what stopped us from getting there.

Then we have to swarm the problem, and remove the barrier. Try it again, and learn what stops us the next time.

The old model shows “standards” as a countermeasure to prevent backsliding, when in reality, standards are a test to see if our true countermeasures are working.

I believe this model of “standards” as something for compliance is a cancer that is holding us back in our quest to establish a new level of understanding around what “continuous improvement” really means.

It is time to actively refute the model.

If you own your corporate training materials, find that slide (it is in there somewhere) and change it.

If you see this model in a presentation, challenge it. Ask what should happen if something gets in the way of meeting this “standard.”

“What, exactly do you expect the team member to do?” That sparks an interesting conversation which reveals quite a bit.

Mark,

Far be it for me to disagree with you or Mike, but let me try something a little different on you. I’d propose that early on in one’s lean journey, performance has probably been stagnant or even degrading for some time. Before one can really go to town on improvements, sometimes we simply need to “stop the bleeding.” One way to do this is to standardize various things. (Standardize to stabilize as someone once said.) If you do this, you’re still using the PDCA process as a wedge to keep from sliding backwards. But Id propose that in the short term, this would be entirely acceptable.

Now looking forward – as we should be – I’d fully agree with you on changing the way we use standards in the PDCA process.

Tom

My objection to the model is not based on it being “inappropriate” but rather that it doesn’t work as a countermeasure.

Friction and entropy in a process are facts of life. The standard is never stable. Either people cope by working around problems, or they are striving to achieve the standard condition by solving them.

That means the only way to get stability is by setting the standard as an active goal and kaizen TOWARD it, rather than the “wedge concept” of trying to kaizen beyond it.

After showing that a new standard method at least works as a demo, thereafter we have a standard continuous improvement question: “If we are not holding standard work, why?”

A causal tree for investigating this question can grow big. Maybe we overlooked something setting the standard. Maybe we’re getting a defect. Maybe somebody tweaked a feeding process. And on and on. No process is steady state forever. Asking the question gives operators things to think about — maybe ideas for creating a process with less waste for the next new standard.

A well done standard method includes triggers to provoke the question of whether we are holding it. A common example is the taped lines between work stations in auto assembly. If you are walking past the line, ask whether you are holding the standard. Has something changed?

Indeed, one can assert that physically struggling to hold standard work is not as smart as continuously asking yourself why you are not holding it.

First off: Where’s Mike’s presentation? Can you post a link to it?

Secondly: I’ve never seen this diagram before but I definitely agree that I don’t like it. PDCA is a wheel that is powered based upon it’s own design and systems. Standards are built into the continuous experimentation and establishment of new hypothesis.

If you need a chock to hold up your PDCA wheel then you don’t have a PDCA wheel. You have a randomly make improvement wheel. I don’t need a chock behind the wheels of my car when I’m driving up hill because I’m powering that progression. I also don’t need a chock behind the wheels when I stop at a light on a hill because I keep it gear.

If you think you are using standards to keep your systems from regressing then I have to ask: Why aren’t you keeping PDCA in gear?

Mark,

Perhaps I should pose my comment a different way. You’re proposing that standards are to be a goal (target condition) that a team is to strive for using the PDCA process. I have absolutely no problem with every single team in a business having goals that they are striving to meet and using Scientific Method to reach those goals.

What I’m looking at is the other end of the equation – the minimum level of performance that we are willing to accept. This can take many forms such as a minimum acceptable cycle time, a maximum number of particles per square meter, a minimum allowable cure time or a maximum queue size. Generally speaking, bumping into one of these minimum acceptable levels is a trigger for escalation. There might be a target condition / goal for each of these measures that teams or individuals are varying distances from reaching. But everybody must know the minimum acceptable level of performance too. For me, that’s maybe a different kind of standard, but it’s a standard none the less.

So maybe we need two kinds of standards. The goal level which we are constantly experimenting (using the PDCA process) to achieve, and the minimum acceptable level which we only know we hit when we do the Check step, then follow with appropriate Actions. So we truly do use the PDCA process for both.

Tom

Tom –

When you say “the minimum level of performance we can accept” it is still used as a comparison point for the actual level of performance.

We still look for a gap between the standard and the actual.

We still strive to hit that, and we stop-call-wait, seek out root cause, and work to resolve the problem if we fail to hit it.

We do the same things whether it is a level of performance we have never hit, or if it is one we routinely hit – we compare actual vs. the standard for each cycle, and trigger problem solving when ever we fall short.

Even if we have never actually achieved the “new standard” we put it into place because it is what we should be able to achieve if the work is problem-free.

And perhaps that is it:

The standard defines the problem-free state. Any deviation from the standard reflects a problem, problems must be acted upon and solved, and solving the problem moves us TOWARD the standard.

Reversing the question –

The “wedge model” appears as though improvement is moving AWAY from the standard.

Realistically, when or why would be try to move away from “the definition of how we want the process to perform?”

Moving the standard to the right side of the wheel (up the ramp) solves a real semantic problem we have all encountered – that you have to “break the standard” to improve the process.

But in reality, in all cases, we are striving to HIT the standard with improvement.

Mark,

To share something on the blog that we were discussing over lunch, it’s helpful to remember the origin of the word “standard”–it’s the flag out front that everyone can see and everyone is marching towards.

From the Online Etymology Dictionary:

Interesting history.

Mark,

I think the image is unnecessary, but it is not incorrect. The wedge says standardization. Taichii Ohno, to add in another quote, is frequently credited with saying something like ‘Without standardization, there can be no improvement.” That seems to be the essence of the wedge.

Another point about the Toyota Kata image.

I haven’t seen the original presentation, but it seems a bit unfair to say that the (well-meaining) author meant to put the responsibility (fault) on employees by saying standardization is necessary to maintain gains, but when Toyota does the same thing with Standard Work, it is a positive.

Just my two cents.

Jeff

“Without standards [to determine what to strive for] there can be no kaizen” – because unless you know what you are trying to achieve, you have no idea whether or not you achieved it.

Here is a question – if you want a standard to be a “wedge” to keep you from sliding back, how exactly does the existence of a standard accomplish that?

How can it work other than holding out the standard as what you are STRIVING to achieve, and responding with escalation, correction, and kaizen when you fall short?

That is how Toyota does it – with a management structure specifically designed to provide support to the team member when ever he DISCOVERS something that keeps him from following the standard – they are striving to achieve it, and using “chatter” or “noise” in the process (deviation from the standard) as in indicator that they still have work to do.

The standard is something you are moving TOWARD with active investment of energy, not something that passively keeps you in place. The system has continuous chaos coming into it, and only active and continuous injection of energy even keeps it stable.

If, on the other hand, you believe that the “standard” is a passive wedge that is somehow holding the process in place… how does it do that again?… then where is the problem solving focused? Is it ignoring problems that keep people off the standard?

And that comes down to the key point” Being able to actually achieve the standard, problem free, is an abnormal condition. Indeed, in Toyota’s culture, it is an alarming condition (“No problem is a BIG problem”) because it means the system has become blind to issues.

Can anyone cite a real-world example where a “standard” actually prevents back-sliding without this continuous CHECK and ACT working to detect and clear problems? Toyota? How about 10,000 andon pulls a day? Every one of them is a departure from the intended standard.

Mark,

Here’s a real-world example for you: Gasoline. There is a standard for what the fuel is so your engine doesn’t burn up. And yet there is still a massive amount of work being done to find alternative, better fuel sources. Are you saying that we should keep looking for differnent fuels, but get rid of standards for gasoline at the pumps currently in use?

I have to say that I truly disagree with your definition of a standard as something you are moving toward. A goal is something you move towards. A standard is something that defines the current process. I am not saying that you should treat standards as permanent, and I am not saying that outside conditions won’t change, but you have to set clear expectations for team members.

As far as Toyota, the 10,000 andon pulls a day you mention occur when there is a departure from a current standard. They are not just randomly pulling the cord. How would a person know when to pull the andon if there was not a standard that they were not going to be able to meet? And more importantly, how many andon pulls has Toyota avoided over the years because they made a clear standard and then improved from there? Toyota very clearly uses the wedge…

Love this conversation, by the way!

Jeff

Toyota avoids andon pulls by respond to andon pulls when the team member is unable, stopped, or otherwise can’t perform the work to the standard.

The standard is the specification against which the actual work performed is compared.

As for gasoline, I would contend that is a symanticly different use of the word. The specification calls out the quality result required. Though similar, I think the context is different enough that the example not germane.

My question remains – is there an example where standard work is a fixed static thing that anchors a process without constant intervention, response, and kaizen to advance toward it?

I don’t look at the picture with the wedge and see static, so I don’t know if that condition on your example matches what the picture shows. The picture doesn’t depict a ‘fire and forget’ standard. I see a dynamic wedge following the rolling PDCA ‘wheel’ up the hill. (Note the improvement arrow). Toyota’s standard tomorrow will not be the same standard as today, but they follow today’s standard (the wedge) religiously while it still is the standard.

I think a relevant example is any one that shows a continuously evolving standard that provides a platform for future work to get better. If you don’t like the gasoline example, how about the evolution of HTML and XHTML? Or the tool we are using to have this conversation? The current version of WordPress is build upon previous code (standard processes) to make it do more things better. Every update is a new wedge that holds that PDCA wheel as it moves steadily up the hill.

This picture actually reminds me of the sawtooth improvement run charts often used in kaizen training. There is normally one that shows the slippage, and the other that shows the stabilization of a process between kaizen activity. That is what I see the wedge as depicting in another way.

Not quite sure I followed the andon pull part of you comment. The way I see the andon process going is that the standard work (the wedge) specifies the dozen plus steps that might go into a process. When there is a problem that would keep the operator from meeting that standard, they pull the andon, and the reasons for the andon pulls power the PDCA cycle. It rolls a few feet up that hill. When a root cause is eliminated, presumably one of those steps gets better, resulting in a new and improved process. A new standard is established, and the wedge is moved to keep that wheel in ins new location. Future andon pulls now happen whenever the updated standard is missed. And so on. And so on. Up the hill….

I’m pretty much with Jeff on this one. I see there being two kinds of standards. There’s the “current standard” which is the minimum acceptable level of performance. This defines the current way of running the business / process and we escalate if we cannot attain it. Simply put, not good business can run without these.

Let’s look at the recently retired Space Shuttle for some guidance here. I think we all know that shuttle crews have lots of procedures that they train relentlessly to. These standards cover all aspects of normal shuttle operation as well as all “expected” emergencies. So these standards are the minimum acceptable level of performance and how to attain it. They are not what NASA would like the crews to try to hit if they can. On the other end, are they a wedge to keep crews from doing something silly? Well, maybe. But, they’re definitely a standard.

The other kind of standard is (to me at least) what Mike Rother refers to as the “target condition.” This is the next minimum acceptable level of performance. It’s what we’re trying to get to. Put in business terms, it’s what we need to be trying to figure out how to do if we’re to keep ahead of the competition. That’s great, but we’re not there yet and we’re definitely not stable when we’re not there yet.

If I might, let me propose that we’re getting into one of those theoretical debates that career acedemics are famous for – and I abhor.

What is interesting to me is that the statement “and we escalate if we cannot attain it” is a statement of general agreement with the entire premise.

The key point is that the “target condition” is a very specific method that you want everyone to try very hard to follow.

This is not “try and do the best you can” this is “follow the standard” in exactly the way that you and Jeff are saying. Every time. Without fail.

Most of the time they succeed.

But in the real world, there are surprises, there is noise in the system, there are sources of instability, there are things that cause you to fall SHORT of the standard that is before you. Those are the things which must be escalated, cleared, and problem solving applied in order to improve the performance of the system.

Then you engage problem solving – that also follows a very rigorous and standardized method – to ferret out the cause. The result of that problem solving is that some process, somewhere in the system, is now going to be operating to a new standard.

Mark,

I think the thing about Rother’s model that rubs me the wrong way is that treating a target like a standard is inherently disrespectful to people.

Essentially, you are asking them to do something that there is not yet a process in place to support. I agree with setting a goal to get there, and I think it is great to expect people to have daily improvement as part of their job.

But until the PDCA wheel has rolled past that new taget, it is an unreasonable request to expect the employees to meet that future standard today. It would be like intentionally shifting a production line faster than the standard work says to. Being able to meet the lower takt is a target, but if the line is not set up for it, the employees suffer.

I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but what I am interpreting from your comments and article is that if customer demand rises, you would advocate lowering the takt time (the target standard) and start shifting the line more quickly immeditately, and then let the PDCA cycle catch the standard work up to the new faster pace. Is that correct? Or am I missing something?

I’d also be interested if anyone knows if that is how Toyota does it. Do they lower their takt time below where the red line is on the SWCS and then expect the team to make improvements to get there? Or do they set a new target, and then devote improvement resources to developing processes that can meet the target before adjusting the pace of the line? If it is the latter, it sounds a lot like the wedge model to me.

Tom…My apologies to you for beating this theoretically dead horse. I worked with Mark for a few years a while back. You should see us debate the nuances of a Lean principle in person…

Jeff

Have you read Toyota Kata to get the full picture of what Mike means by “target condition” and a context for the presentation we are discussing?” Because it isn’t anything like that at all.

Mark,

Just ordered Toyota Kata. From what I have seen though, I am skeptical that the message is fundamentally different than treating standards as a way to hold gains while focusing on continuous improvent.

Also found an interesting Deming quote to go with the Ohon qoute.

According to Deming: “It is important that an aim never be defined in terms of activity or methods”

According to Ohno (as menitoned earlier): “Where there is no Standard there can be no Kaizen”

When you create a standard, how often do you expect the user’s to follow it? Do you expect them to be able to follow the standard 100% of the time?

What if we can only follow the standard 99.9% of the time and the other .1% of the time variation in the process forces the systems to be run outside of the boundaries set by the standard? What would you call the standard then? A “standard” or a “target condition”? I think everyone can agree that no standard can be followed 100.00% of the time forever.

The target condition is to be able to run to the standard 100% of the time. When you create a new standard and you go out to the floor and tape up the new way things are going to be done, adherence to that standard is likely 0%. Nobody has seen it before so why would it be followed? So what do you do? Well, you layed out a plan with the new standard, now you have to let the process run and see if the plan is followed (Do). You watch how the plan is followed (Check) and then you teach (Adjust) the operators how it works. This will likely have to repeat on multiple shifts and will require multiple loops before the majority of the instability in Man/woman is gone.

Then what happens? Material changes and Machines breakdown so we have to Adjust the process once again or we may have to change the standard to match a new understanding of the process. After a while, we get to a point where we are able to follow the standard 99.9% of the time and we look at each other, smile, and retire into happiness.

So the only difference between what Mark is saying and what Jeff is saying is the percent of time you should be in compliance to the standard. Traditional management would tell you that the higher the number the better. The closer you are to 100% compliance to all of your standards, the better off your business is.

Toyota would call this lazy. “NO PROBLEM IS PROBLEM!” If you have a specification that you can drive a truck through, you will undoubtedly swerve….

When standards are created, it sets the pace of improvement. Why does Toyota have so many andon calls? Because they set their standards high enough that the standard is difficult to follow. Do you think that they set up standards and then unexpectedly had 12,000 things go wrong. No. They set up the standard expressly expecting 12,000 opertunities to improve. They also set up a support structure and management systems that could handle every one of those opertunities.

You have to be careful not to set standards that will overwhelm the resources available to solve problems. You also have to be careful not to set the standards so low that no improvement is occuring. Most people treat their standards like biblical commandments. In reality they are more like toleranced specifications. How tight of a tolerance do you need?

Once you are running to the standard so often that improvement has ceased, you need to evaluate your standards to determine if you are meeting your strategic objectives. Generally, by the time you have stability (ie ability to follow the standard) business objectives will tell you that your status quo isn’t good enough and you will have to set a higher standard.

The real motto: If you system aint broke – Break it!

Hi Mark,

Great post and great discussion. It helps me further in my thinking on the topic. I think there needs to be a lot more disussion on this, I’m not able to grasp it fully yet. I think this is partly because in a way, our understanding of change management in complex environments is still in it’s infant stage.

I used your blogpost on my blog, I’ll come back here if it generates different discussions. The first link below is the original in Dutch and the second is the Englisch translation by Google.

http://leandenkenindezorg.blogspot.com/2011/10/pdca-borging-vaak-verkeerd-gebruikt.html

http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=nl&u=http://leandenkenindezorg.blogspot.com/&ei=yzriTeLFGpG8-Qb6oNHcBg&sa=X&oi=translate&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDcQ7gEwAA&prev=/search%3Fq%3Dlean%2Bdenken%26hl%3Den%26client%3Dsafari%26rls%3Den%26prmd%3Divns

I ran into Mike Rother at the Northeast Shingo Conference in Springfield, MA last week. Really nice guy. I actually got to talk to him for about 10 minutes on this very topic and told him about my struggles with it. We had a really good discussion with Mike whipping out a piece of paper for both of us to sketch on as we talked. He did offer that this one had generated lots of discussion and I think he had a much better understanding of my issues – and maybe possible better ways to talk about this topic – in the future. Did I say he was a really nice guy?

Tom

Great discussion. I agree with Rother & Mark. The standard should be on the other side of the PDCA wheel.

I think Liker’s new Continuous Improvement book has a great quote to support this discussion:

“So how does Toyota sustain the gains? The answer is that Toyota does not see the Toyota Production System as a mechanistic process of implementing an improvement. It sees TPS as an organic process of continuous improvement. Any improvement is simply one more countermeasure to learn from. If we focused on sustaining the gains, we would stop improving.”

Kata clearly discusses to identify a realistic standard based on current conditions and then use PDCA to remove the barriers between existing condition and the standard (the gaps). At no point is the standard used as a compliance measure but it is used to reveal problems.

Standards are also supposed to move closer to ideal condition. “The Birth of Lean” has two Ohno quotes to support this as well:

“If you’ve got three pieces of work-in process, reduce that to two. If you’ve got two, reduce it to one. The ideal is to get it down to zero.”

“Attaining a target doesn’t mean that you’ve finished anything. Targets are just tools for tapping people’s potential. When you’ve attained a target, raise the bar.”

Maybe some of the debate here lies in the difference between standards and standardized work. The SW is meant to help achieve the standard.

It seems we are overthinking the wedge graphic. It’s a metaphor for the fact that without an agreed, attainable and documented standard to fall back on, it is irresponsible to attempt kaizen (PDCA) because when the process changes (the wheel starts rolling back) it’s not clear if you’ve improved or devolved.

I don’t believe Mark or Mike are advocating getting rid of the standard on which PDCA rests, and without which Taiichi Ohno tells us there can be no kaizen. But they don’t give us an alternative after “retiring” the wedge to the left of the PDCA wheel.

An enrichment of the wheel and wedge metaphor would be to show it in 4D, that the wedge moves up the plane, from side to side, even backwards depending on changing conditions (loosened tolerances for different applications, greater allowances for fatigue as the workforce ages, etc.) over time.

The wedge is not a driving force for PDCA. It does not push the wheel. It is the ground floor. There must be a ground floor, a base level of performance, even if it is only achieved 97% of the time – that is the standard. The “ideal” is 100%, which is the proposed “wedge” to the right of the PDCA wheel and at the top of the hill. But we really don’t need that one since there is arrival point, only the pursuit of perfection. It should be more of a chalk line to which you want to move the wheel and standards wedge up the inclined plane.

I’ve been reading Toyota Kata. It is a great book, despite me disagreeing about the whole wedge graphic.

My view is that despite saying to retire the wedge, Rother actually advocates using it. For example, he talks about removing kanbans to stress the system, which extends the target/target condition he mentions. But the kanban system itself is the standard. It defines the current state. Without having that in place, the PDCA ‘wheel’ would never gain traction.

But as a few people have now mentioned, the wedge / no wedge discussion is moot. Everyone seems to believe you need some stability to make improvements, regardless of how you depict it.

I do not believe we should retire the wedge. The graphic makes sense and is easily understood in a training situation. I agree with the previous contentions that the standard is not the goal. In the context of the graphic, standards are about the way we do things, not the outcome we are hoping to achieve. The standard is the starting point for kaizen. It defines the process until we find a better way which becomes the new standard and so on up the hill of improvement. The graphic doesn’t show a top to this hill, you are always moving upwards. Each time you kaizen the standard you are creating a point below which you should not drop. If you do then it’s time to do some problem solving. I think it’s a simple concept that is being over-thought here. Then again, I do have a very simple mind…

I think the key is found in Jerry’s comment:

That implies that the mere existence of a standard does not stabilize anything.

The standard only provides a point of reference.

We compare the actually executed process against the point of reference each and every time we carry it out.

To do that we have to construct the process in a way that departures from the standard are immediately apparent. We can’t wait for an audit.

WHEN, not if, (because this is the real world) something causes the process to depart from the standard, we are, by definition, “below the set point” on the “ramp.”

The action is to engage problem solving (which is kaizen) to eliminate the cause of the issue, and try again.

Even if the standard works the vast majority of the time, if now and then we are below it, then on average, we are not at the level set by “the wedge.”

We are trying, each and every time, to work to the standard, and checking if we succeed.

When we don’t succeed, we are getting really curious about why, and working on that.

In the process, we get better.

I was looking though some corporate training materials the other day and saw a reference to this post. This is definitely fascinating. It is amazing how often people get stuck in a rut with their way of thinking. I really appreciate this.