The first official day of KataCon kicked off with a keynote on deliberate practice by Billy Taylor. I first met Billy back in 2012 when I was doing some work with Goodyear. When I saw him at last year’s KataCon it was like running into an old friend, but that is who Billy Taylor is – even if you just met him.

Billy Taylor on Deliberate Practice

Pull quotes and thoughts

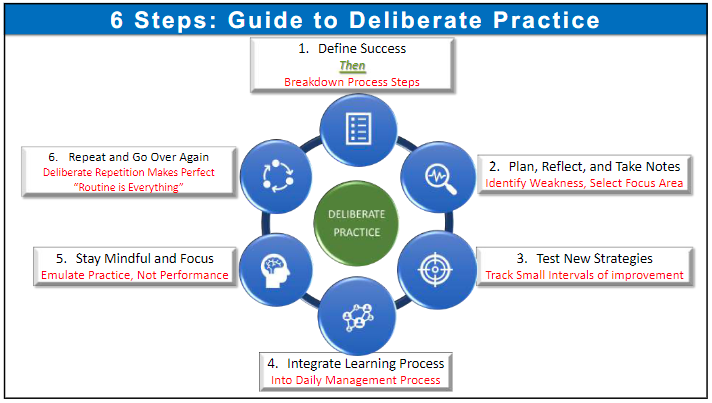

The Concept of Deliberate Practice

- Toyota Kata has two sides, like a coin. On one side is scientific thinking. On the flip side is deliberate practice.

- Traditional practice is often just mindless repetition. Deliberate practice has focused attention on perhaps one aspect of the routine.

A couple of things come to mind for me here. First is that too many coaches go through mindless repetition of the Coaching Kata. They just ask the next question on the card, and never practice using the questions to nudge the learner’s thinking to the next level.

This means they never practice in a way that pushes them as coaches. More about that below.

The other is that we, all too often, take a learner through the entire process much too fast. We do this in classes to give them a taste of the whole process. But in real life, perhaps it would be best to anchor each Starter Kata step and ensure there is at least understanding before moving to the next.

When 2nd coaching it is equally important to focus both the coach AND the learner on improving a single aspect of the board.

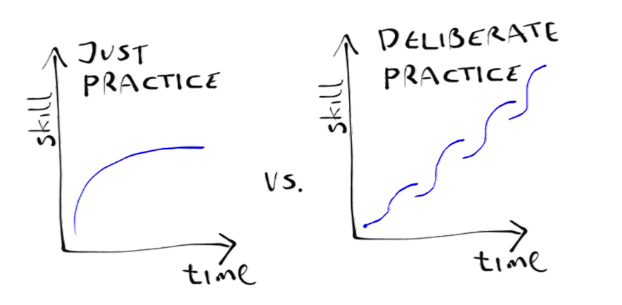

As I am writing this, I am reflecting more, and parsing more. This slide offers a ton of insight for me:

There is so much here on a lot of levels.

This is how I interpret the graphs: On the left we have “Just Practice.” Maybe I am learning to play a song on the guitar. As I practice I learn to play it better and better. Then I hit a plateau because I am comfortably good and not challenging myself anymore. I am just playing. And that feels awesome, because I validate to myself that I am pretty good.

At a higher level, this is the “lean plateau” that so many companies hit. They get really good at running kaizen events, or black belt projects, or whatever they do. They hit a pretty good level of performance, but things erode. They reach a plateau when the implementers are spending all of their time re-implementing what has eroded. They shift into mindlessly repeating the familiar rather than challenge themselves. What are we missing? Why is the skill concentrated into the same half dozen individuals who have been doing this since 1999?

The graph on the right represents something that is the same, but different. Take a look – each little squiggle repeats the graph on the left, only smaller. Each time a plateau is hit, the learner challenges herself to practice a new aspect. Things get a little worse for a bit, then as the new aspect is mastered, the process is repeated.

I see the job of the coach as two fold:

- To challenge the learner in small steps, always looking for the obstacle to the next level of performance.

- To offer up specific things to practice.

Billy’s presentation covered a lot of overlapping territory – enough for at least two more posts – stay tuned.

This article intrigued me with the difference between scientific thinking and deliberate practice. This is extremely applicable to Lean Six Sigma because one pillar of Lean is continuous improvement. As soon as you become complacent with a process and begin to plateau, you are no longer improving and this can contribute to waste. Once upon a time, a process might have been new and innovative, but as mentioned in the article, it can become stagnant over time. Once workers stop looking to improve it and are just going through the motions, the company is losing money. I like the balance the author presented using the coach example. A coach should offer guidance in small steps to keep his players on the right track, while also deliberately practicing certain aspects of their strategy to stay up to date and maintain their edge.

Scott –

You hit on a really critical factor in continuous improvement: There is no stable steady state.

You are either actively working to improve your process, or it is slowly eroding.

I like to say it is like a freezer. You can’t ever say “OK, the freezer is cold enough now, so I can unplug it.”

As a minimum you must take active measures to deal with the little things that always come up, and problem-solve to eliminate the cause (or, at the least, the effect).

This requires active effort – a continuous input of energy – to just keep things where they are.

Very interesting article. The deliberate practice graph seems to represent flow in learning and development. Thanks for the insight!