I’ll admit right up front that the headline is worded to attract search engines.

If that’s how you got here, be prepared to think.

Can You Prove That This Works

This is something I hear a lot:

“I can see where _____ applies to your example. But my process is __(different somehow) ___.

Fill in the blanks.

Other versions are:

- “I can see how that works in manufacturing, but ____.

- “How does this apply to _____?”

- “Can you show me examples in (something that is an exact match to what I do)?

Anyone in the business of process improvement has heard versions of this excuse for years. It always comes up. “I can see how that works for cars, but we make ____.” is an older version.

One of my favorites came via a friend working with a Japanese supplier to Boeing. They told him “We can see how this would work in American culture, but we don’t think it works in Japan.” Yes, we were teaching Japanese management techniques to the Japanese, and they were telling us it doesn’t work in Japan.

So… this style of “Prove to me that this applies to my specific situation” is something we’ve all heard again and again.

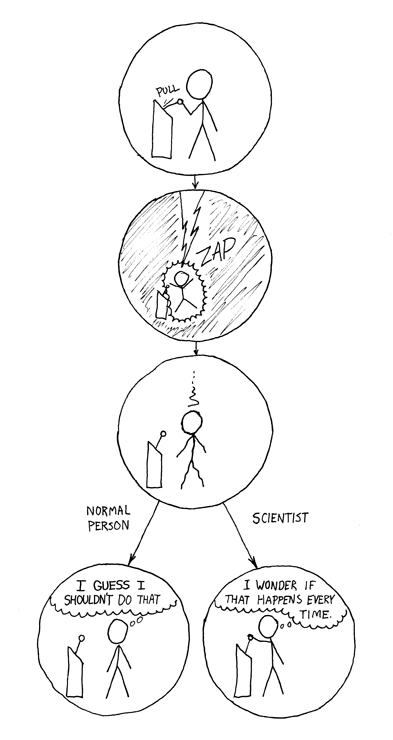

Science

If you manage to read all the way to the bottom, you will see that I readily concede that I cannot prove that “Toyota Kata” or learning problem solving based on scientific thinking works to improve any process out there.

To be able to prove that, I would need knowledge of all processes, past, present and future, and have to make the case that, in each and every one of them, I have indeed established that it works.

What I do have is personal knowledge of application in a very diverse circumstances, which adds to the collective experience of thousands of people who are working to apply these methods and principles. So far, we haven’t found that case where it can’t work. We might someday, but haven’t yet.

The assertion that this thinking is universal is a refutable hypothesis. You can, with some effort, establish rigorous proof, through repeatable experimentation or direct observation of a counter-case that my theory needs modification.

But before we get to that part (at the end), let’s go through some more common instances of this line of thinking.

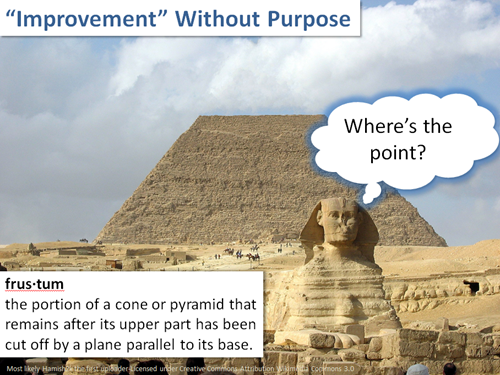

The Instance of Product Development

Here are a couple of things to think about.

Let me ask, “How do you do product development?”

Typically (HOPEFULLY!) I’ll get some version of:

- Understand what we are trying to achieve – performance specifications, customer needs, etc. that today’s product cannot provide.

- Assess the baseline capability and identify gaps between what we need to do, and what we can do with technology, manufacturing capability, etc.

- Based on that, establish the first, or next, of what are likely a series of intermediate goals converging on the requirement.

- Iterate through cycles of trials, tests, experiments, learning, etc. to converge on a design that meets the requirements.

Now, to be clear, there are LOTS of variations on this, and lots of ways to manage the execution of this thought process. Some are dramatically more effective than others, but at the core there is a rigorous application of the scientific method.

What is the alternative? Guess at something, build it, and hope it works? Even that approach is going to (hopefully) have you going back and assessing what you learned when it doesn’t work.

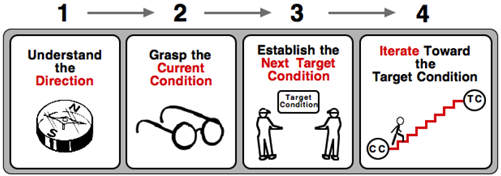

So what, exactly, is it about the methodology we are teaching with Toyota Kata that is any different from the above?

- Understand the challenge and direction.

- Grasp the current condition.

- Establish the next target condition.

- Iterate from the current condition toward the target condition using a rigorous scientific approach that drives learning.

Why wouldn’t you want to apply that method to R&D? What do you do, if you don’t do this?

And, to be even more clear, I think I can make the case that all of the exotic product development methodologies – “Production Preparation Process (3P),” “Agile” and it’s cousins, “Lean Start Up,” “Design for Six Sigma,” “Set Based Concurrent Engineering,” all of them, are simply methods to cycle through the this learning process faster, cheaper, and more robustly.

Toyota Kata is nothing more than a tool to teach the thought pattern. Don’t lose sight of that.

Here’s the kicker. What we are doing, in reality, is working hard to figure out how to apply robust product development thinking to production processes, not the other way around. This stuff started in R&D. The Wright brothers used this process between 1899 and 1903 and beyond to the first practical airplane in 1908. Wilbur’s diaries and letters are essentially a PDCA cycles record.

Scientific Process Engineering

In spite of the little rant above, most engineers take a lot of care to design the product. They study and understand the details of its function, and carefully make modifications in a controlled way so they can test the effects of what they are doing.

On the other hand, it is relatively rare to see the same rigor applied to designing the production process. Many times it is allowed to come together ad-hoc. There is often deep understanding of the core value-adding process steps – how to do machining, welding, painting, etc. But the design and management of the movement of material and information from one process step to the next? Not so much.

Why wouldn’t you want to learn how to apply the same rigor in designing the production system that you apply to designing the product itself?

What is the alternative? Actually I know what the alternative is. Set financially derived metrics, and a high-stakes rewards system for hitting them. Then leave it to managers to figure out on their own. While you’re at it, divide the system into functional areas and set those managers up to compete with each other’s performance. It is a robust system with a reliable, repeatable outcome. Maybe not the outcome you would seek intentionally, but reliably predictable nonetheless.

So how about giving a thought to applying scientific design principles to your production flows? It can’t make them any worse.

Back to Engineering

In a large engineering department, most of the activity isn’t research and design work that I discussed above. It is production work. The products are drawing changes, bills of material, quotes and estimates, CNC programs, engineering change notices, resolution of production problems. This is all vital engineering work, but it is production.

Each of those products is assembled from components. The “material” might be information, but if you decompose outputs into their constituent components, you see sub-assemblies coming together from smaller bits, and in turn, assembling into the bigger “thing” whatever it is.

This is a factory. It just makes useful information rather than hardware.

The irony is (1) There typically even less attention paid to how things are done, what struggles people have to get the information they should have gotten, but didn’t, etc. then there is in even the worst manufacturing floors. And (2) There is often little realization that even people sharing the same cubicle often are working to different interpretations of the requirement, much less methods of doing the work.

So here’s a question:

Are you (as a manager) expected to improve the lead time, quality of output, productivity… any of those things… in your department?

If the answer is “No” then great. I’m glad to hear that things are working perfectly for you… though you might want to spend more time understanding what people are really dealing with, because “No Problem” is often a BIG problem.

For most, though, the answer is “Yes.” They are expected to deliver some improvement in throughput, quality, productivity, etc. Note that these are all production system measurements. That makes perfect sense, because, as I said, these processes are production.

OK… you’re on the hook to deliver improvement of some kind.

How are you going about improvement in your process?

Indulge me a bit, and let me ask a couple of questions.

- What you are trying to achieve with your improvement?

- How is your process performing today in comparison to that? Do you know what it is about the process that is driving that current performance?

- What are you working toward, right now, as the next step to reach your goal?

- What kinds of things are you going to have to fix or change to get there?

- Which of them are you working on now?

- Can you share a bit about what kind of things you are trying in your improvement effort? How are they working for you?

I realize that Toyota Kata might not apply, but if you are actively working to improve anything, you likely have answers to some form of those questions (hopefully).

Of course, those are a variation on the Toyota Kata coaching questions, aren’t they?

It’s just that we usually don’t ask and answer questions like this explicitly. Maybe the effort would be a little more focused and clear if we did. Because all we are trying to do with Toyota Kata is make the scientific thought process more explicit so it is easier to teach. The idea is to get more people learning and understanding how to think that way, which I believe is generally a good thing. Most people would agree, at least with that last part.

I Still Need A Specific Example

Here’s where I sometimes scratch my head, especially when I get this question from someone with a technical education, and often a graduate degree on top of it.

When you went to those universities, did they teach you with examples that exactly matched the job you are doing today? Likely not. Yet you have figured out how to apply those principles to what you are doing.

In those classes, seminars, case studies, they used problems and examples to help you understand the principles.

Then they expected you to take the specific instance of those principles from the examples they used, turn them into a general case, then figure out how to apply those general principles to a different problem, case, or set of circumstances.

In the end, that is really all they were teaching you: How to figure out how to apply a general principle or theory to a specific case or problem. They likely didn’t accept an exam answer that said “You didn’t show me an exact example of this problem.”

It’s Still Science

I will totally concede that there may well be specific instances where the general principles of scientific thinking wouldn’t work to improve a particular type of process. And in those cases, there is certainly no benefit to working to learn how to apply, and teach, scientific thinking.

I say that because I believe in the scientific method, therefore my assertion that “These principles are universally applicable” is a refutable hypothesis.

I welcome the discovery of a specific case where they don’t apply. But the other side of the scientific method is I cannot prove the non-existence of that case.

If, on the other hand, you can establish that you indeed have the proverbial “Black Swan” on your hands, let’s take a look. The burden, though, is on the person suggesting to refute the hypothesis to provide compelling evidence.

Can you please explain what it is about your specific process that defies application of scientific thinking to understand it better, and improve it? What specific characteristics would a process have that makes it so unique that you are stymied in any attempt to apply what you have been educated and trained to do as a scientist or engineer?

I am really curious, and welcome exploring that together, and perhaps modifying my theory to adapt to any true anomalous situation.

That’s science.

“,

“,