Continuing on the theme of value stream mapping (and process mapping in general) – in the last post, Where is your value stream map? I outlined the typical scenario – the map is built by the Continuous Improvement Team, and they are the ones primarily engaged in the conversations about how to close the gap between the current state and the future state.

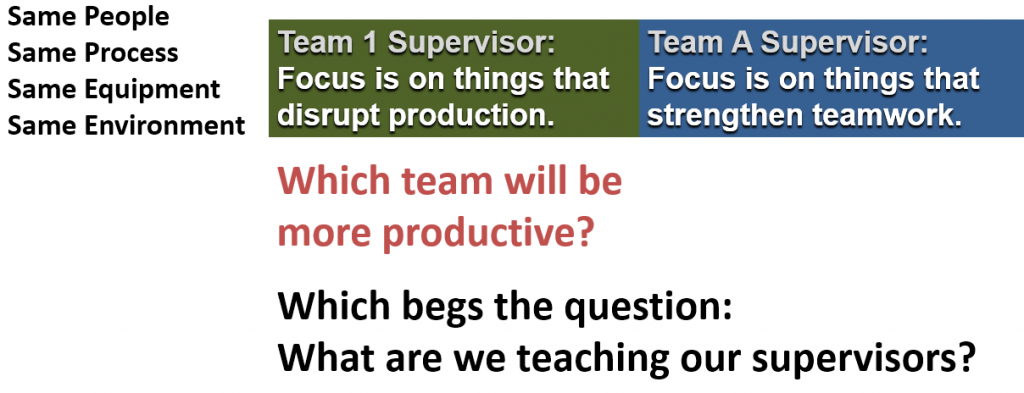

The challenge here is that ultimately it is the line leadership, not the Continuous Improvement Team, that drives whether or not this effort is long-term successful.

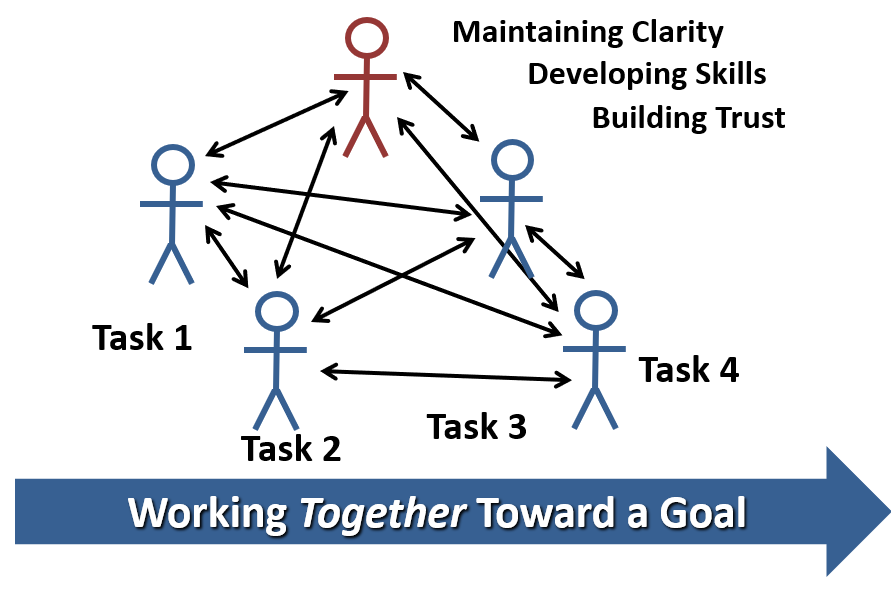

Getting a continuous improvement culture into place means changing the day-to-day patterns of interaction between people and groups of people. We can put in all of the lean tools we want, but if those conversations don’t follow, the system quickly reverts to the previous baseline.

What is interesting (to me, but I admit I’m a geek about this stuff) is that this is a meta level thing. While we are working on improving the performance of the value stream, we really have to be working on the performance of the process of leadership in the organization.

The value stream map can help with this, but we have to be deliberate about it, and realize that it will be an incremental and iterative process, just as we find in trying to improve how any process functions.

Start With Where You Want To Go

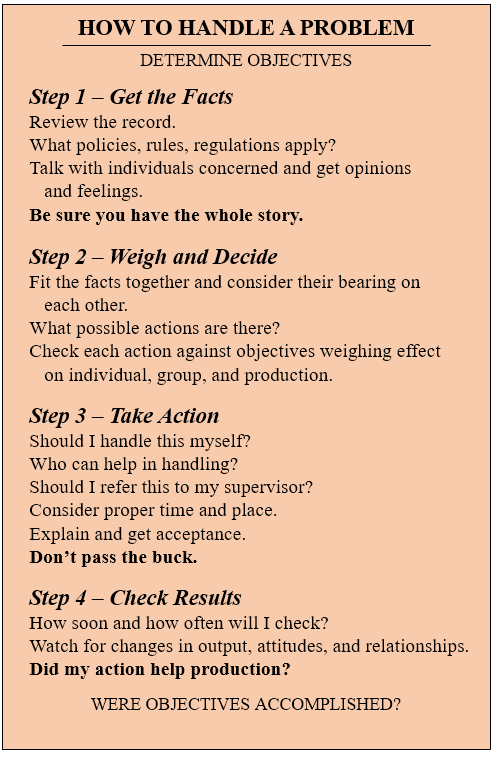

For line leadership, before we even start drawing process boxes, the first step is deciding why you are even doing this. What problem are you trying to solve? What aspect of your current performance needs to change… dramatically?

Is your system unresponsive to customers? Do customers expect deliveries inside your nominal lead times? Does that disrupt your system? What lead time capability would let you routinely handle these issues so they weren’t even issues anymore, just normal operations? That objective is going to bias your current state VSM toward understanding what is driving your lead times, where, when, and for how long, work is idle vs. actually being processed, etc.

Or maybe you need to increase your capacity while holding your costs (vs. just duplicating the existing processes). Now you are going to be focusing on the things that constrain your throughput, activities that consume time within cycles of output and the like.

Establishing that focus is a leadership / management task. It doesn’t work to just say “We need to improve” or even worse “We need to get lean.”

Sometimes these things are obvious frustrations to management, but often they are overwhelmed with general performance issues, or trying to define problems in terms of financials. That is an opportunity to focus back on the kind of performance that would address the financials.

The cool thing here is that you really can’t get this wrong. If you set a goal of radically improving your performance on any single aspect of your operation, you will end up improving pretty much everything in the process of reaching that goal. But it is critically important to have a goal to strive for, otherwise people are just trying to “improve” without any objective.

Then map your current state. The challenge gives you context. The current state map gives you a picture of how and why the system performs as it does.

Just so we don’t get sucked down the whirlpool of focusing too much on the business process in this discussion, the reason why you are getting this clarity is to get (and keep) the leaders engaged. If the objective is something abstract like “get lean” it is easy for them to think they can just get updates while they deal with the “real issues.” We want to attach this to a real issue that they are already working on.

Thus there is no “lean plan.” So many companies make “lean” somehow separate from other business objectives. I never could understand that. Maybe they are trying to separate “gains” that are a result of the “lean program” from those created by other initiatives. It doesn’t work that way. There is only one operating system in play, and that is what drives your day-to-day performance. If you don’t like the performance, you have to change the operating system. That is a management function, and it can’t be delegated.

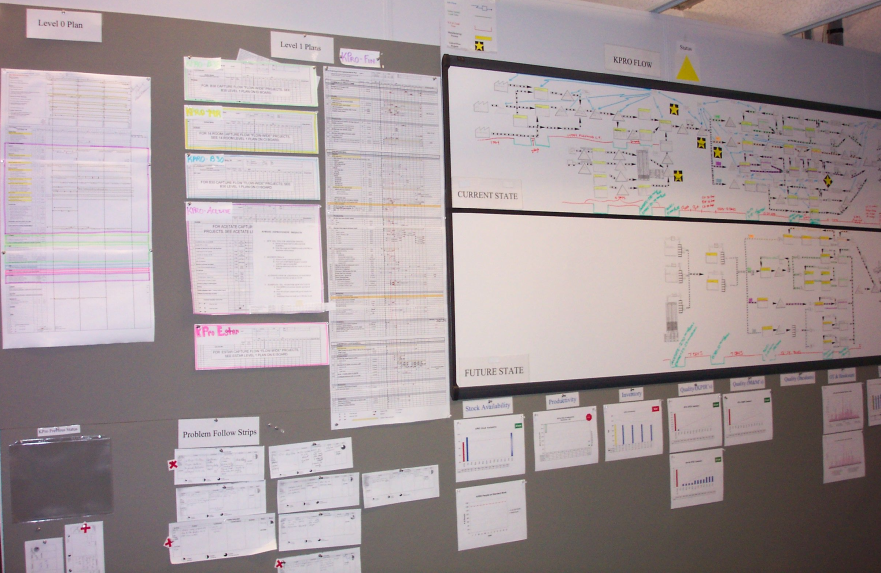

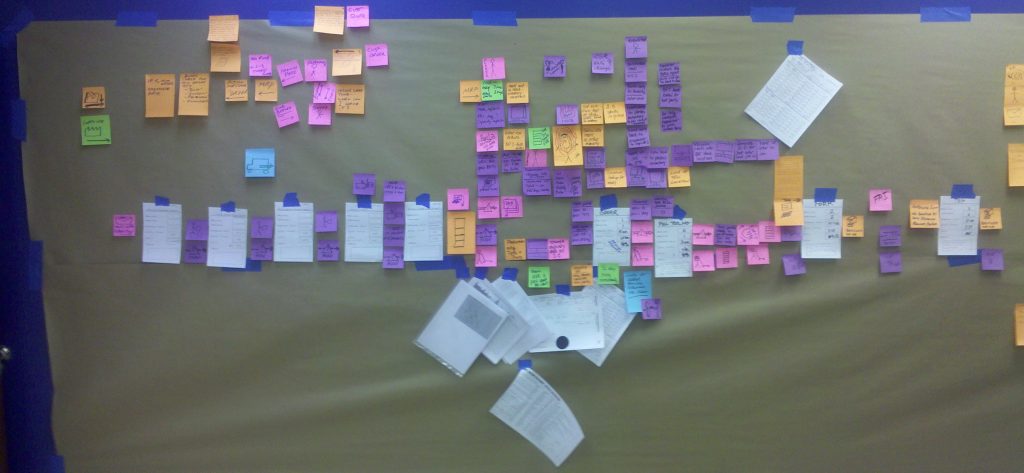

The photo above is a current state map from a process that took several weeks to ship a part that the customer had ordered. Since it was a make-to-order shop, this was, shall we say, challenging for the customer relationship people.

As the team built the map it began to sink in that the time actually making the part was less than 30 minutes, and the value add was about six of those minutes. Their performance metric was “Past Due Hours” which was an abstraction of the programmed jobs that were behind the promised ship date.

Because the customers were always asking the business team members, “Where’s my stuff?” those customer reps were, in turn, always on the shop floor trying to get their orders expedited. They were competing with one another for a place in the production queue.

There is an icon in the middle of the map. Here is a close up:

This is Jim. He was an hourly associate whose nominal job was to pull the paperwork, match it up with raw material, and stage the work package into the production queue.

But this role made him the gatekeeper. So the customer service people (you can see their names in the lower left corner) would be pressuring Jim to jump their hot orders (and they were all hot by the time it got to the point where there was paperwork release – another story) into the queue so they could tell their customers that their orders were “in production.”

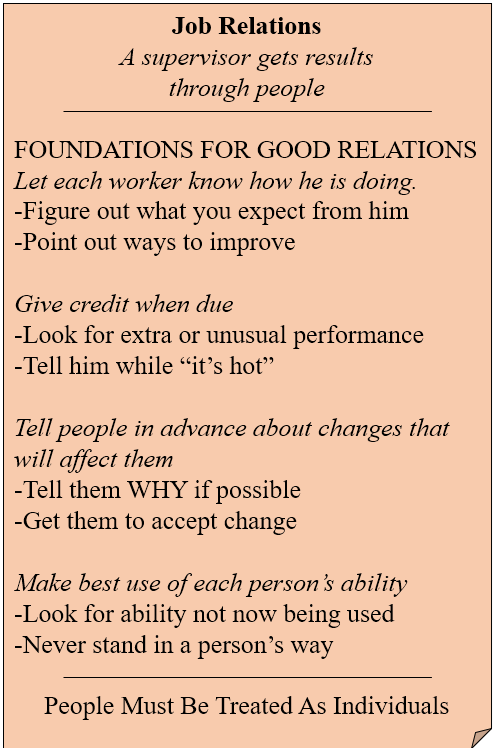

This put Jim in the position of having to make the priority decisions that the leadership wouldn’t make. Ultimately it was Jim who decided which customers would be disappointed that day. That made his day way more stressful than his pay grade. Respect for people? Hardly.

It also resulted in a staged order queue (materials and paperwork on carts) that snaked through the shop until it finally (days later) got to the actual production cell which, once they started, could actually knock things out pretty fast.

None of this addressed the past due issue. In fact, this made it worse.*

The key question for this team was “Who needs to have what conversation about work priorities so it isn’t all on an hourly associate to decide which of our customers will be disappointed?”

Who Needs To Fix This?

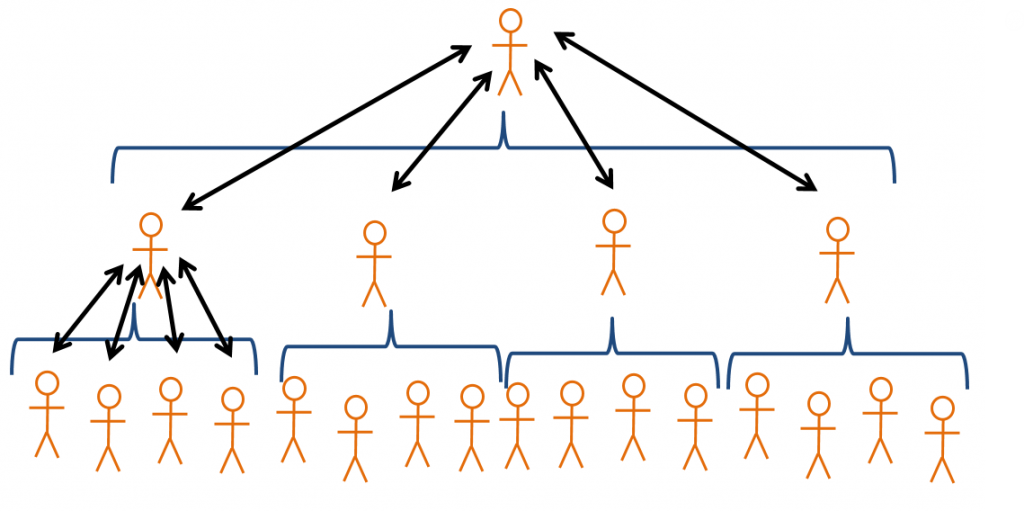

We want to solve problems at the lowest possible level, but no lower. In this working example, asking the shop floor workforce to fix this problem would be futile. Yes, they can propose a different structure, but they do not control how orders are released, they do not control how capacity is managed, they do not control the account managers who are fighting for a spot in the queue. They had been complaining about this bind for a long time. It wasn’t until the people running the business saw how the overall system worked that they understood that this is a systemic issue, and “the system” belongs to line management.

The facilitation question that got their attention was “Do you want Jim to be the one who decides who gets production priority?” Of course the answer was “No.” And that wasn’t about Jim, rather it was the realization that this WAS the existing process, and that wasn’t how they wanted things to operate. As my friend Brian says, “You may not like your normal, but you have to deal with it.”

That is generally the case at the value stream level. Value stream problems are usually at the interfaces between processes. The shop floor can’t, for example, transition from a push scheduling system to pull on their own. If they try, they create conflicts with the existing scheduling system and this usually tanks their metrics – even if performance is actually getting better.

These are all management discussions.

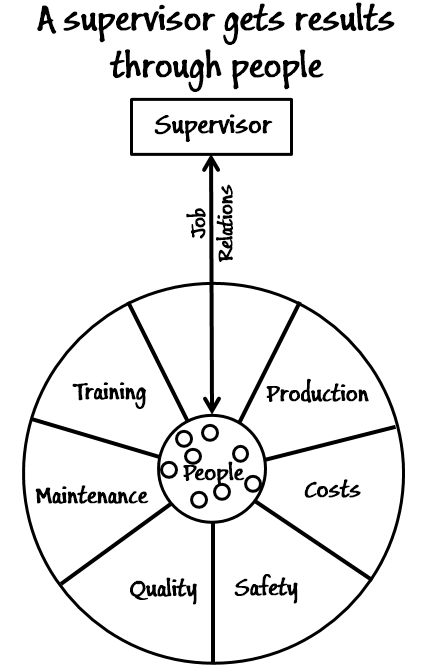

Key Point: The value stream level is a systems view. While you absolutely want input from the people who are engaged in the work every day, working on the system itself is not something that can be delegated by line leadership. They are the ones who are responsible for the overall system, and they are the ones who need to be responsible for changing it.

The Future State Map is a Hypothesis

Once you understand the current condition, the next step is to answer the question, “How does the process need to operate in order to meet our goal?”

The purpose of mapping a future state is to design process flow that you believe will meet your challenge if you can get the system to work that way.

It isn’t about seeing what you could do by removing waste. It isn’t “what could we improve,” it is “what must we change to reach our objective?” Again, this is a management function. It’s called “leadership.”

Which brings me to the title of this post.

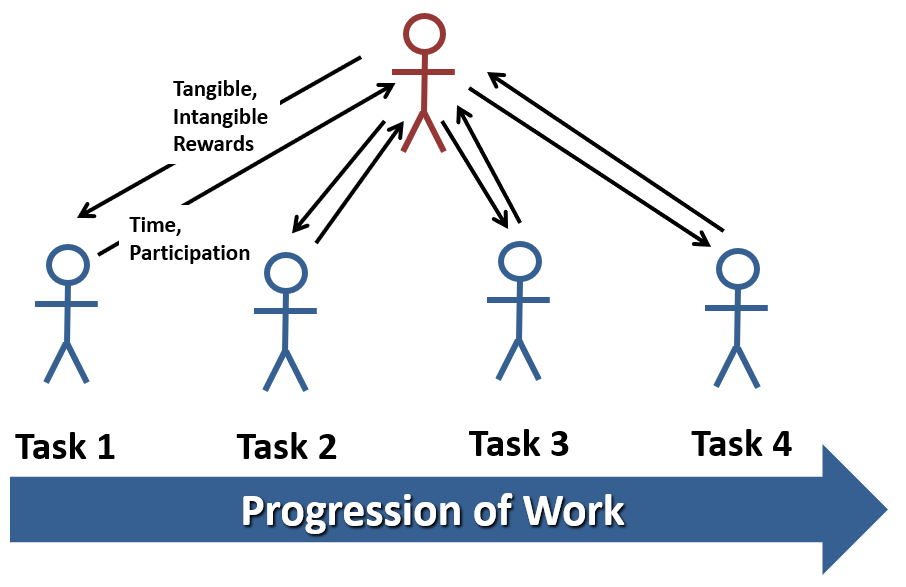

Who Is Talking About This Stuff?

If the Continuous Improvement Team simply facilitated the process for line leadership (the actual stakeholders) to grasp the current condition and establish a target (future state) condition, what is crucial is who takes ownership of closing the gap. If the C.I. team are the ones discussing the problems they are often in a position of having to sell and justify every step of the effort to get to the future state.

Likewise, I have seen a lot of cases where the people primarily participating in building the value stream map were working level team members. Yes, it is absolutely necessary to have their insights into how things really are for people trying to get stuff done. Yes, it is critically helpful for them to understand the bigger picture context of what they do. However, all too often, I see senior leaders disengaged under the umbrella that they are “empowering” their workers.

Just to be clear: We absolutely want to create conversations about improvement at the level of the organization where value and the customer’s experience is actually created. The point here is that those conversations cannot be the exclusive domain of the working levels. It is critical for line leadership to be, well, leading. They can’t just delegate this to the continuous improvement specialists. Nor can they simply leave it to the working levels to sort it out – not if they expect it to work for any length of time.

Who reports on progress?

When an executive wants to know the progress toward an improvement goal, who do they call? Do they call the continuous improvement team to report? Or do they call the actual stakeholder who is responsible?

This is an easy trap to fall into. The C.I. Manager wants to show they are making a difference. The senior manager knows the C.I. Manager probably has better information. But that isn’t the conversation we want to create. The conversation needs to be between the line leaders. Yes, the C.I. team can (and probably should) help structure that conversation, but if they inject themselves into the middle (or allow senior management to put them there) the vital vertical connections are weakened – if they ever existed.

Thus, it is critical for the Continuous Improvement team to have a crystal clear picture of who should be having these conversations, and be actively working to nudge things in that direction. This is the process the C.I. team should actually be working to improve.

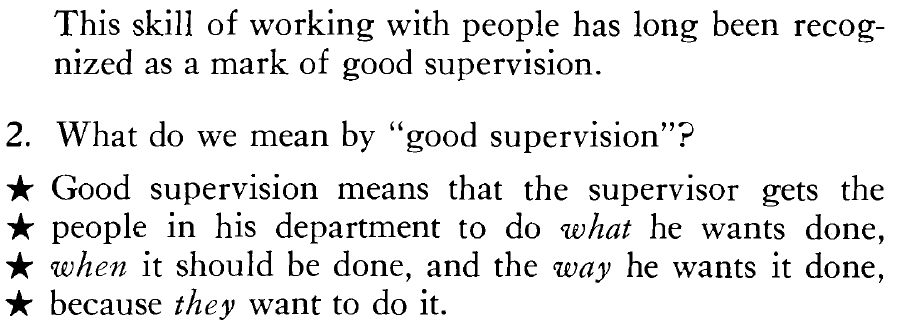

What should people talk about?

Ah, here’s the rub. For some reason managers today have a reluctance (or even disdain) to talk about operations, preferring to keep conversations in financial terms of cost, earned hours, yield and the like. These are all outcomes, but they are outcomes of process, and it is only by changing the process that those outcomes can sustainably change.

That conversation about progress I talked about above? That can’t be solely about the performance. It has to be about what is changing in the way the work is being done, and more importantly, what is being learned.

What the future state value stream map does (or should be used to do) is translate those business objectives into operational requirements for the process.

What Is Your Target Condition?

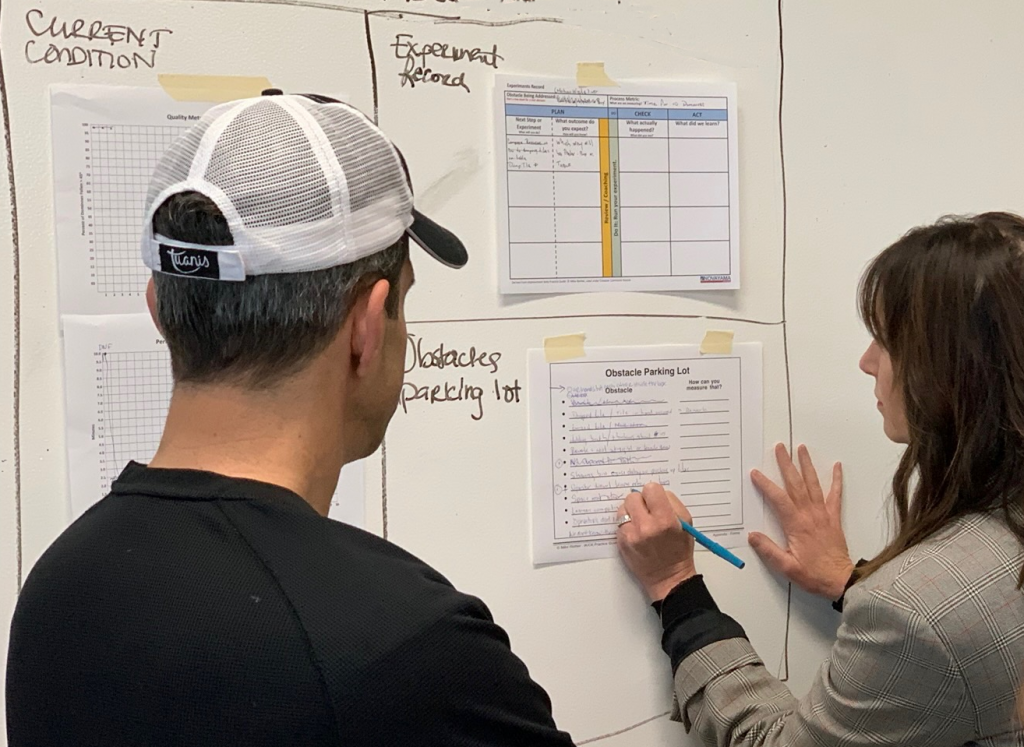

How we start to see the organic intersection between Toyota Kata and the value stream map.

The future state map defines a management goal. It also highlights the problems that must be solved to get there. (Those are the “kaizen bursts” that Learning to See has you put on the future state map.)

Those problems, or obstacles in Toyota Kata terms, at the value stream level become challenges (again in Toyota Kata terms) for the respective process owners.

Now the conversations move to the right level. Rather than asking for the status of action items for the “lead time reduction initiative,” the line leaders are discussing progress toward getting the changeover in stamping down to 17 minutes, and the cycle times in the weld cell under the takt time.

In my working example above, the first target condition was to have Jim simply pull the next order from a FIFO queue in a series of slots on the wall. The customer service reps had to meet every morning and could reshuffle the orders in those slots all they wanted, but Jim’s job was just to take the next one. That pushed the initial conversation to the one they had been avoiding: The customer service team talking among themselves, rather than making Jim the arbitrator.

There was a lot of other work as well. They established a rigid FIFO with a fixed WIP level of staged orders. Instead of pushing days of work into that queue, there was a buffer of about an hour (to absorb variation in processing times between various jobs).

At the same time, the team running machines now understood the rate of processing that was required to keep up with the volume of work. That had been totally hidden by the queues before. All they knew is that they were behind. Now the conversation shifted to “Are we going fast enough?” It shifted from discussions about backlog (which really are not productive) to discussions about rate of processing which is the only thing that affects the backlog.

Getting all of this dialed in and stable took a few weeks of daily conversations between the Operations Director and the various managers and supervisors whose work impacted the flow. It involved walking the floor, putting in visual indicators that clearly defined what should be happening – the target condition – and they discussed reasons things looked different: The actual condition now, and what obstacles were being surfaced as they worked to reduce the WIP buffers.

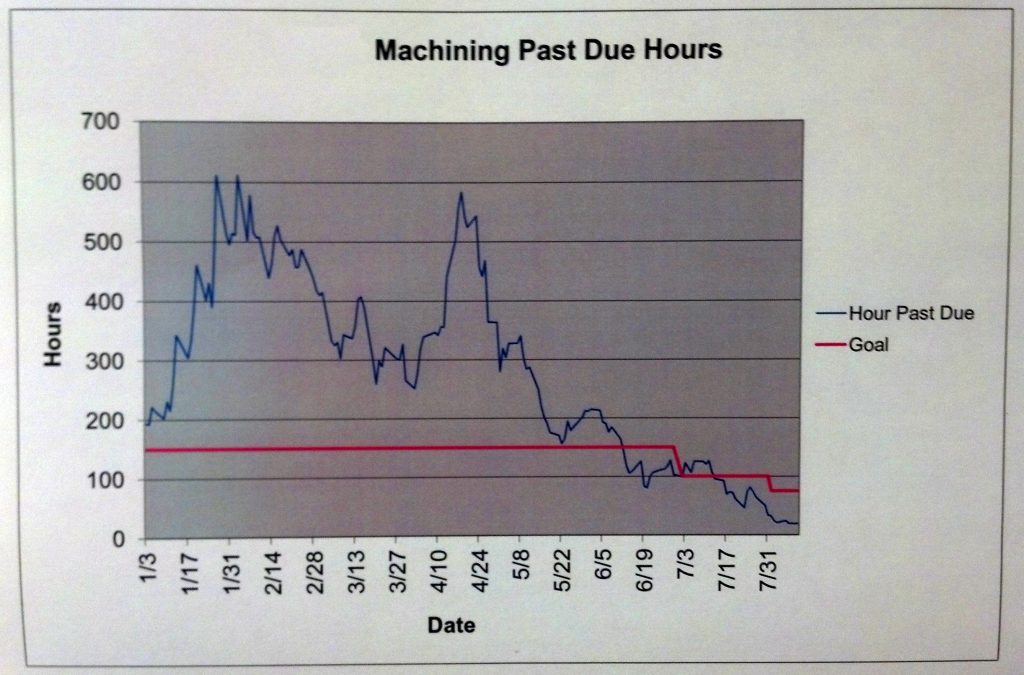

The net result?

Learning is Critical

The current performance is an outcome of the current system. People do their best within the system they have to work within, and we have to assume the system reflects management’s understanding of how things should operate to get the best results.

Even if someone knows a better way, that knowledge is wasted unless it is applied to the overall system of operating – the way we do things.

Epilog

You would never say “The freezer is cold enough, we can unplug it now.” You have to keep putting energy into the system just to keep the temperature where it is. Tightly performing production systems are no different. Over the course of the next year or so past due hours slowly crept back up for unknown reasons. Why? Because they didn’t talk about it every day.

*When a shop is behind, the management reflexes are (1) increasing batch sizes and (2) expediting. There really aren’t any better ways to make the throughout and response times worse.