Background:

I wrote an article appearing in the current (October 2017) issue of AME Target Magazine (page 20) that profiles two very different organizations that have both seen really positive shifts in their culture. (And yes, my wife pointed out the misspelling “continous” on the magazine cover.)

The second case study was about Meritus Health in Hagerstown, Maryland, and I want to go into a little more depth here about an element that has, so far, been a keystone to the positive changes they are seeing.

Sara Abshari and Eileen Jaskuta are presenting the Meritus story at the AME conference next week (October 9, 2017).

Sara is a manager (and excellent kata coach) in the Meritus CI office. Eileen is now at Main Line Health System, but was the Chief Quality Officer at Meritus at the time Joe was presenting at Ka taCon.

taCon.

Their presentation is titled Death From Kaizen to Daily Improvement and outlines the journey at Meritus, including the development of executive rounding. If you are attending the conference, I encourage you to seek them out – as well as Craig Stritar – and talk to them about their experiences.

Mark’s Word Quibble

In addition, honestly, the Target Magazine editors made a single-word change in the article that I feel substantially changed the contextual meaning of the paragraph, and I am using this forum to explain the significance.

Here is paragraph from the draft as originally submitted. (Highlighting added to point out the difference):

[…][Meritus][…] executives follow a similar structure as they round several times a week to check-in with the front line and ensure there are no obstacles to making progress. Like the Managing Daily improvement meetings at Idex, the executive rounding at Meritus has evolved as they have learned how to connect the front-line improvements to the strategic priorities.

This is what appears in print in the magazine:

[…][Meritus][…] executives follow a similar structure as they visit several times a week to check in with the frontline and ensure there are no obstacles to making progress. Like the MDI meetings at Idex, the executive visiting at Meritus has evolved as they have learned how to connect the front-line improvements to the strategic priorities.

While this editing quibble can easily be dismissed as a pedantic author (me), the positive here is it gives me an opportunity to highlight different meanings in context, go into more depth on the back-story than I could in the magazine article, and invite those of you who will be attending the upcoming AME conference to talk to some of the key people who will be presenting their story there.

Rounding vs. Visiting

In the world of healthcare, “rounding” is the standard work performed by nurses and physicians as they check on the status of each patient. During rounds, they should be deliberately comparing key metrics and indicators of the patient’s health (vital signs, etc.) against what is expected. If something is out of the expected range, that becomes a signal for further investigation or intervention.

“Visiting” is what the patient’s family and friends do. They stop by, and engage socially.

In industry, we talk about “gemba walks,” and if they are done well, they serve the same purpose as “rounding” on patients in healthcare. A gemba walk should be standard work that determines if things are operating normally, and if they are not, investigating further or intervening in some way.

I am speculating that if I had used the term “structured leader standard work” rather than “rounding” it would not have been changed to “visiting.”

Executive Rounding

Joe Ross, the CEO at Meritus Health, presented a keynote at the Kata Summit last February (2017). You can actually download a copy of his presentation here: http://katasummit.com/2017presentations/. The title of his presentation was “Creating Healthy Disruption with Kata.” More about that in a bit.

The keystone of his presentation was about the executives doing structured rounding on various departments several times a week. These are the C-Level executives, and senior Vice Presidents. They round in teams, and change the routes they are rounding on every couple of weeks. Thus, the entire executive team is getting a sense of what is going on in the entire hospital, not just in their departments.

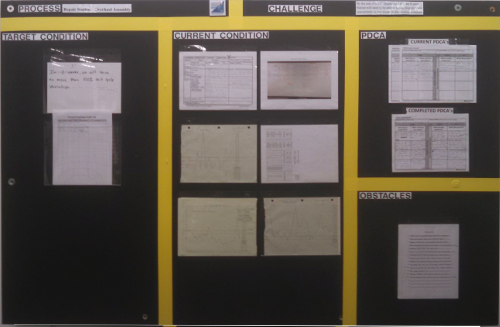

Rather than just “visiting,” they have a formal structure of questions, built from the Coaching Kata questions + some additional information. Since everyone is asking the same basic questions, the teams can be well prepared and the actual time spent in a particular department is programmed to be about 5 minutes. The schedule is tight, so there isn’t time to linger. This is deliberate.

After the teams round, the executives meet to share what they have learned, identify system-wide issues that need their attention, and reflect on what they have learned.

In this case, rather than rounding on patients, the executives are rounding to check the operational health of the hospital. They are checking the vital signs and making sure nothing is impeding people from doing the right thing – do people know the right thing to do? If not, then the executives know they need to provide clarity. Do people know how to do the right thing? If not, then the executives need to work on building capability and competence.

In both cases, executives are getting information they need so they can ensure that routine things happen routinely, and the right people are working to improve the right things, the right way. In the long-term, spending this time building those capabilities and mechanisms for alignment deep into the operational hierarchy gives those executives more time to deal with real strategic issues. Simply put, they are investing time now to build a far more robust organization that can take on bigger and bigger challenges with less and less drama.

Results

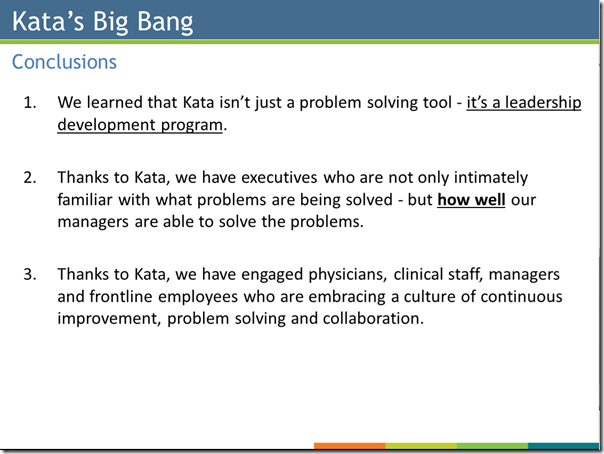

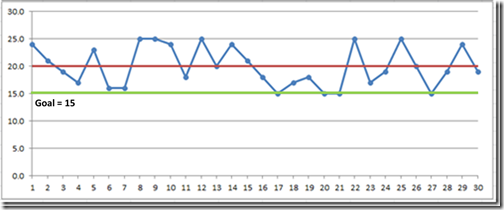

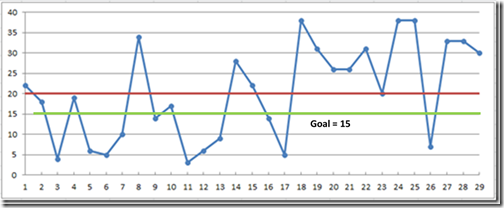

Though they were only a little more than a year in when Joe presented at KataCon, he reported some pretty interesting results. I’ll let you look at the presentation to see the statistically significant positive changes in employee surveys, patient safety and patient satisfaction scores. What I want to bring attention to are the cultural changes that he reported:

Leadership Development

Actually points 1. and 2. above are both about leadership development. The executives are far more in touch with what is happening, not only in their own departments, but in others. Even if they don’t round on their own departments, they hear from executives who did, and get valuable perspectives and questions from outsiders. This helps break down silo walls, build more robust horizontal linkages, and gives their people a stage to show what they are working on.

Since executives can’t be the ones with all of the solutions, they are (or should be) mostly concerned with developing the problem solving capabilities in their departments. At the same time, rounding gives them perspective on problems that only executive action can fix. In a many organizations mid-manager facing these systemic obstacles would try to work around them, ignore them, or just accept “that’s the way it is” and nothing gets done about these things. That breeds helplessness rather than empowerment.

On the other hand, if a manager should be able to solve the problem, then there is a leader development opportunity. That is the point when the executive should double down on ensuring the directors and upper managers are coaching well, have target conditions for developing their staff, and are aware of who is struggling and who is not. You can’t delegate knowing what is actually going on. Replying on reports from subordinates without ever checking in a couple of levels down invites well-meaning people to gloss over issues they don’t want to bother anyone about.

Breaking Down Silos by Providing Transparency

The side-benefit of this type of process is that the old cultures of “stay out of my area” silos get broken down. It becomes OK to raise problems. The opposite is a culture where executives consider it betrayal if someone mentions a problem to anyone outside of the department. That control of information and deliberate isolation in the name of maintaining power doesn’t work here. Nobody likes to work in a place like that. Once an organization has started down the road toward openness and no-blame problem solving, it’s hard to turn back without creating backlash of some kind within the ranks.

Creating Disruption

Joe used the term “Disruption” in the title of his presentation. Disruption is really more about emotions than process. There is a crucial period of transition because this new transparency makes people uncomfortable if they come from a long history of trying hard to make sure everything looks great in the eyes of the boss. Even if the top executive wants transparency and getting things out in the open, that often doesn’t play well with leaders who have been steeped in the opposite.

Thus, this process also gives a CEO and top leaders an opportunity to check, not only the responses of others, but their own responses, to the openness. If there are tensions, that is an opportunity to address them and seek to understand what is driving the fear.

In reality, that is very difficult. In our world of “just the facts, ma’am” we don’t like to talk about emotions, feelings, things that make us uncomfortable. Those things can be perceived as weakness, and in the Old World, weakness could never be shown. Being open about the issues can be a level of vulnerability that many executives haven’t been previously conditioned to handle. Inoculation happens by sticking with the process structure, even in the face of pushback, until people become comfortable with talking to each other openly and honestly. The cross-functional rounding into other departments is a vital part of this process. Backing off is like stopping taking your antibiotics because you feel better. It only emboldens the fear.

These kinds of changes can challenge people’s tacit assumptions about what is right or wrong. Emotions can run high – often without people even being aware of why.