Chapter 3 of The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership is titled “Coach and Develop Others.”

Chapter 3 of The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership is titled “Coach and Develop Others.”

Where in Chapter 2 the authors were outlining the individual leader’s responsibility for self-development, now they are describing the environment and the process of supporting and focusing that drive.

Rather than just outline the chapter, I want to dig into some key elements of the context that Toyota creates for their leaders.

First is the expectation that leaders lead.

Leading vs. Delegating

Chapter 3 has a great story that exemplifies the key differences in management styles that I alluded to in the post about Chapter 2.

In that story, NUMMI has equipment reliability problems in the body shop. Mr. Ito, the President has instructed Convis to have each engineer prepare and present a one page report for every breakdown lasting over 30 minutes. The telling moment is Convis behavior in the presentations:

While Ito was critiquing the [A3] presentations and reports, Gary [Convis] simply stood to one side, marveling at Ito’s insight and amused at the struggles of the engineers’ efforts to learn this way of thinking.

This quote nails the core issue we have to deal with in any company that wants to succeed with lean production.

Convis was newly hired from the U.S. automobile industry, and was acting exactly as he was trained as a manager. He was acting as every manager in the USA is trained.

He has delegated the process of training the engineers to Ito, who he sees as the technical expert. Convis viewed his presence here as overseeing how well his engineers are responding to that training.

Ito, though, had other ideas.

After a few sessions, Ito asked Gary how he was coaching the engineers through the process before the presentations. Ito pointed out that there was still a lot of red on the reports, and if Gary had been teaching the engineers properly, there would be less red ink. […] problems with the reports were a reflection of Gary’s leadership, and he was more responsible for any failures than the engineers were.

Zing.

You can’t even cite “If the student hasn’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught” here because the delegation paradigm was so strong that Convis didn’t realize he had responsibility for being the teacher.

Convis, of course, “got it” and began seeing the red ink as his failure, rather than the engineers’. The drive for self-development kicked in and worked. And of course, in the process of struggling to coach the problem solving process, he had to struggle to learn it well enough to do so.

Personally, I see the idea of delegating and then passively overseeing improvement and people development is a cancer that is difficult to excise from even the most well intentioned organization.

I have seen this with my own eyes – senior executives struggling with how to “implement lean.” What was their concern? What metrics they could use to gage everyone’s progress through reports to corporate headquarters. They simply saw no need to get personally involved in learning, much less going to see, and certainly not teaching, the messy details. Not surprisingly, that company still struggles with the concepts.

Of course it cascades down from there. The various sites’ leaders follow the example, and delegate to their professional staff people. The staff’s job? To come up with “the lean plan” and “drive improvement” while the leaders watch. At some point, someone in charge of the operation actually has to do something different, but that, it seems, is always the next level down.

I am not going to get into what stops leaders from stepping up to this responsibility or what do to about it because that would be a book in itself.

It doesn’t help that, with the revolving-door of leadership we often encounter, each new leader comes in with the old mindset. OK </rant> and back to the book.

The Technical Support

This expectation of leaders leading does not operate in a vacuum. Toyota processes are deliberately set up to remove any ambiguity about what the next challenge is by surfacing problems immediately

In the words of Lean Leadership, these problems are framed as challenges for leader development.

In a much earlier post, I objected to our western euphemism of “opportunity” when we meant “problem.” My objection was treating this “opportunity” as an something that could be taken on, or not.

A challenge, especially in the context of leader development, isn’t optional. A top level athlete grasps the meaning of a challenge. He is driven to take it on and push himself to meet it. He improves in the process. It isn’t about the record, per se, it is about what he must develop and pull from within himself to get there.

Just as the world-class athlete has a stopwatch on every lap, the assembly line is set up to verify the timing of every cycle. Any discrepancy is immediately apparent to both the team member and the leaders. If the work can’t be done, the line is stopped and things are made right. Then we figure out why. And everyone learns.

TPS […] creates a never-ending stream of opportunities for on-the-job development and increased challenges. Toyota sensei do not need to create artificial training situations […]. The daily process of producing cars generates all the development opportunities and challenges that are needed.

If your organization has trouble finding problems, it isn’t because they aren’t there. It is because your processes are blind to them. That is why “No problem is a big problem.”

The key is that when we talk about “implementing the tools of lean” we are doing nothing more than setting up the baseline process to present the challenges for leadership development. That’s it. It is the difference between playing a casual game and deciding to keep score.

You can’t improve without keeping score, to be sure. But keeping score alone doesn’t cause things to get better. If anything, it increases people’s frustration because they see they are coming up short, but don’t have the support or opportunity to do anything about it.

What happens then? They start seeing problems as “normal” and start blinding the system. They add padding to cycle times to “allow for variation.” They decouple processes and put in extra inventory. They start running two at a time, then four, and return to batching.

If a problem remains hidden below the surface long enough, it can stop being perceived as a problem and become part of normal operating procedure.

OK, so I’ve beaten that to death yet again. It is critical to structure the work so that we can see whether things are going as planned or not.

But it is just as critical to have the problem solving processes engaged immediately. If those processes don’t yet exist, you have no hope of your so-called improvements sustaining for long.

That’s not all. There is another standard that is just as critical – if not more: A standard for problem solving.

The A3

We just got done exploring how critical it is to have a process that is totally transparent. Why? So we can clearly see any difference between how it is and how it should be.

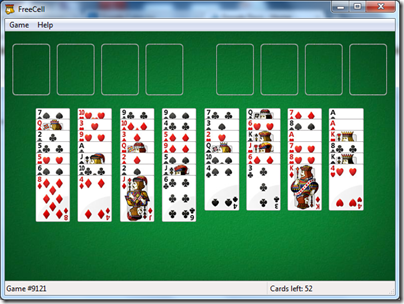

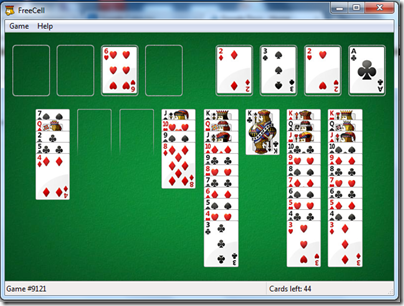

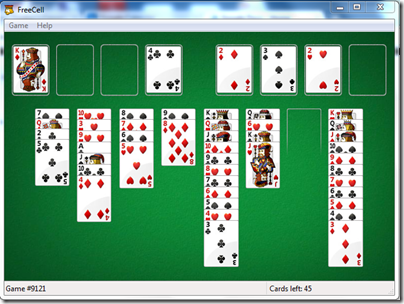

The purpose of the A3 is to provide that level of visual control to the problem solving process itself.

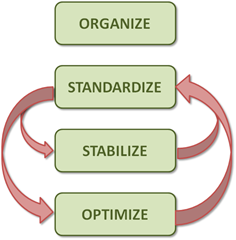

And yes, problem solving is a process. It follows standard work. It is perhaps the most critical thing to standardize. The only way to gain skill at something is to practice against a clear standard. It really helps to have a coach watching your every move and calling out small adjustments, things you need to pay more attention to the next time you do it (which should be immediately).

The A3 is the game film, the slow motion camera, the visual control of how problem solving is being done. It is not sufficient to find the solution. It is more important to develop a consistent approach to problem solving across the entire organization.

But outside of Toyota and a few companies that are starting to grasp what this is about, the A3 is, sadly, one of the more recent fads in the lean community.

An A3 isn’t something you tell someone else to do. It is a visual control, just like the moving line, that works only in the context of direct observation and participation by all parties involved. In the above story, Ito was setting an example, and expecting Convis to follow it. Once that started happening, Ito’s participation shifted from coaching the engineers to coaching Convis as he coached them.

Just as the tools of takt time, standard work, pull systems, etc. do not stand alone and “make you lean,” neither does filling out A3 forms. Even if you have “the tools” and a problem solving process, it doesn’t help if they are not intimately linked together.

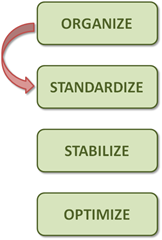

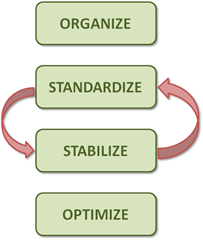

All of these things are designed for 1:1 interaction. They are messy testaments to the fact that problem solving often loops back to previous steps as more is learned.

The Big Picture

This chapter provoked a lot of thought for me, and I have tried to share some of that. When / if you choose to read the book, I hope you have your own thoughts, and even share them here or in the forum (that could use some life right now).

Fundamentally, Chapter 3 is about the phenomenal support Toyota provides those leaders who have the self-motivation to learn.

- Every operation is structured to provide challenges and opportunities for them to develop their skills. There is no shortage of things that obviously need improving.

- Every leader is positioned to teach and mentor those who are willing to step up to the challenges that are there.

- The problem solving process itself is structured as standard work so that a prospective leader can practice against a standard and improve skill through repetition and coaching.

Aside from a couple of case studies and examples, this chapter is a bit of a synopsis of Toyota Kata. I continue to bring Kata into this discussion because there is obvious overlap in topics, and I see these two books complimenting each other. Kata gets into the nitty-gritty of how problem solving and coaching happens. Lean Leadership is providing a context and case examples of the entire ecosystem.

More to follow.