One of the artifacts of Extreme Programming as practiced by Menlo Innovations is the Story Card. In the purest sense, a story card represents one unit of work that must be done by the developers to advance the work on the software project.

But the content and structure of the story card make it much more powerful than a simple task assignment. The story card is written in a way that engages the programming pair doing the work.

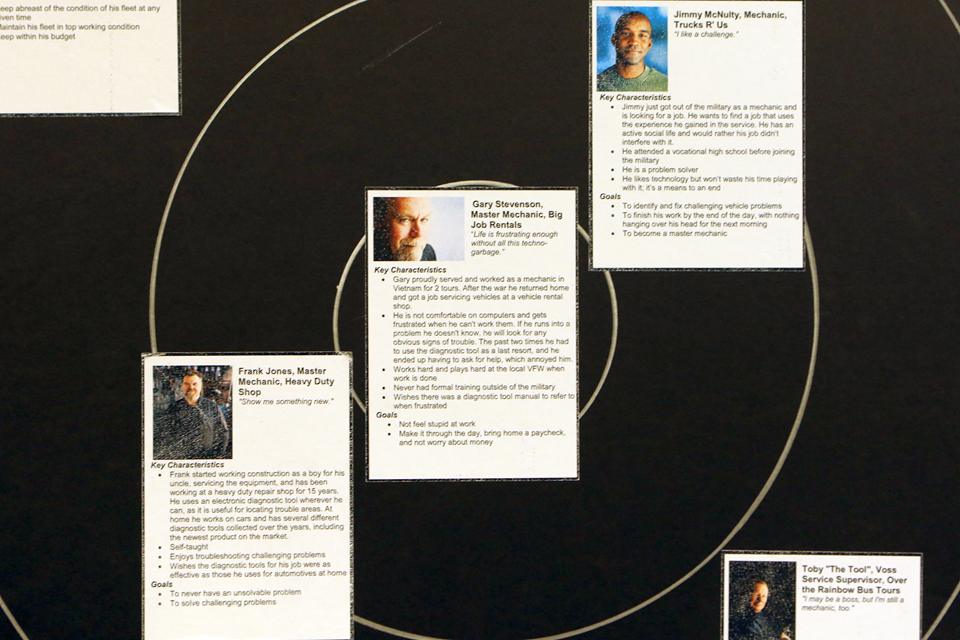

Before a story card is created the team works very hard to identify the primary persona that represents the human being who most benefits from their work. That persona gets a name, a face, a biography. She has wants, needs and aspirations.

Why? A couple of reasons.

First, it establishes priority of effort. In software development compromises must be made between optimizing the interface and workflows for various users. By identifying the primary persona, the team says “This person’s use of the software will be optimized.” Other users will certainly be accommodated, but any compromise will break in favor of the primary persona.

Menlo, for one, works very hard in the up-front design process to smoothly integrate the workflow created by their software into the larger context and workflow that their end-user is trying to carry out.

The other effect is more subtle. It humanizes the “user” as the developers are talking about what their code does, or does not, do.

Rather than simply set out a feature in an abstract way, the story card focuses on granting an ability to the main persona. The process of creating the personas, and developing the persona map humanizes the group of people that would traditionally be thought of as “the users.”*

Thus, the feature would be described something like this:

“Sara is able to select her choice of color from a pull-down menu of options.”

Then the developers write code that enables Sara to do this, quickly and easily.

This is a simplification, but it suffices to set up my main point.

Who Are You Optimizing Your Improvements For?

Let’s translate this thinking into our world of continuous improvement.

Who is your key persona? Who are you enabling with your process improvement? What will this person be able to do that, today, he cannot?

Rather than saying “The lowest repeatable time does not exceed 38 seconds” as a target condition, what if I said “John is able to routinely perform the work in 38 seconds when it is problem-free.”

I don’t know about you, but I feel a lot more emotionally engaged with the second phrasing. This is doubly true if John is an actual person actually doing the work.

What about scaling to other shifts, other operators?

Yup. I agree that at some point your target condition is going to shift to “Any trained team member” but what I tell people today when they are trying to go there first is this:

“If you can’t get it stable with one person, you are never going to get there with multiple people.”

You have to get it to work once first. Then introduce the next layer of complexity. Start simple. One step at a time. Control your variables.

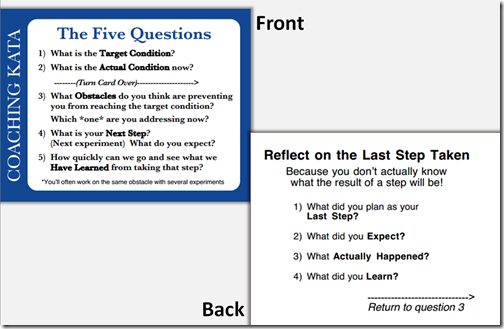

I have been experimenting with this linguistic shift in my Toyota Kata classes and consulting.

If you are in R&D this is an even more direct application back to Menlo’s model.

Training = Giving People Ability

I also ran an experiment with a client HR team that was charged with developing a comprehensive on-boarding training process.

Rather than do the traditional thing, which is take the laundry list of topics they are supposed to try to cover, and trying to figure out how to stuff everything into the time they have been given (40 hours, which is really more like 35 hours), I asked them to experiment with the following:

For each skill they have been asked to train, write it on a separate 5×7 card in the form of “[The learner] is able to _________.” In other words, describe the skill as an ability that someone is able to demonstrate.

Then determine how they will test that skill. Do that before they even think about how they are going to teach it.

Then develop training experiences and exercises that they believe will allow the learner to pass the test.

Software developers will recognize this as “test driven development” – start with the unit test, then write the code.

Testing Your Target Condition

As in the example above, a target condition should also be testable. By stating what we will observe or measure when the target condition is met, we are constructing a “unit test” of sorts.

By stating what we will observe or measure first, we can separate “solved” from “the solution” and open up the possibilities of what solution(s) we will experiment with.

—————–

In the culture of many more traditional software development and I.T. organizations, “users” can be almost a derogatory term, with an implied, usually (but not always) silent “dumb” appended to the front. We write Books for Dummies so they can understand our brilliant systems.